Prayaag Akbar and Karen Lord with Afua Hirsch: Spectacular New Futures

This discussion, chaired by journalist and author Afua Hirsch, was between two writers of speculative fiction focusing on exploring the kinds of societies that can be envisaged by the genre. Prayaag Akbar was born in Calcutta in 1982, and has degrees in Economics from Dartmouth College and Comparative Politics from the London School of Economics. Known for his commentary on marginalisation in India, he discussed his debut novel, Leila. Karen Lord, a speculative fiction writer with a multifaceted background as a physicist, diplomat and soldier, was born in Barbados in 1968. With a Science degree from Toronto, a Masters in Science and Technology Policy from Strathclyde, and PhD in Sociology of Religion from Bangor, Lord is the author of several books, including the award-winning Redemption in Indigo. She discussed her second novel, Best of All Possible Worlds, published in 2014.

Akbar read an excerpt from Leila in the voice of mother Shalini, reflecting on the moment when a sinister mob kidnapped their three year old daughter, and imagining what she might be like now, sixteen years later. As we shared in the poignant memory of her little girl, we could easily imagine her innocent face as ‘he pinched her cheek between his hairy knuckles’. His book is set in a fictional Indian city based on both Bombay and Delhi, exploring the many societal divisions within cities that result from caste, class and religion. Leila is set in a so-called dystopian ‘near future’, but many of the horrors foretold within it, as the author stressed, are already coming to pass. Best of all Possible Worlds takes place in the distant future on planet Cygnus Beta, filled with refugees from various disasters, and explores issues of what makes a successful multicultural society. The Sadiri people have been running from genocide and are now desperate to preserve their culture. We were treated to tantalising glimpses of dialogue and metaphors from the book, such as “All Sadiri may be considered family”, and “all my knowledge of him was newly minted.”

Lord explained some of her complex process of invention, including the influences from experiences in the many places she’s visited and would still like to visit, such as the forests of Guyana, Australia’s Sydney, and the island of Malta. As the reader is taken on a ‘road-trip’ of the planet, New Zealand’s magical landscapes, known to her and many other outsiders from the Lord of the Rings movies, also make an appearance. She draws much from her own socio-economic research, so much so that one reviewer sniped that it was a story of ‘bureaucrats in love’. Many a sideways swipe at Barbadians from other Caribbean people are based on this ‘Little England’ stereotype, but seeing government through romantic eyes is a refreshing one, however you look at it. Hirsch wryly made the point that even the idea of government as competent and positive is unusual.

Hirsch heralded Best as an optimistic and positive book, with its celebration of successful multiculturalism and peace contrasting with the inverted message of Leila, which faces up squarely to the terrifying challenges currently presenting themselves on the Indian sub-continent. Akbar, as an Indian Muslim, has personally experienced an increasing level of discomfort when making everyday choices like choosing where to live. Protagonist Shalini is a Hindu married to a Muslim, a situation that reflects modern tensions and often fatal interventions in interfaith-unions. Lord laughed as she hoped that she wasn’t being overly optimistic, but explained that the present reality of the multi-cultural Caribbean is very much reflected in Cygnus Beta. Despite some difficulties, distinct groups of people can be absorbed as part of a larger community while simultaneously holding on to aspects from where they originated, with the idea that group identity is both natural and positive.

Hirsch was the perfect chair, as a journalist, author and TV personality who is currently at the heart of British debate around questions of identity and politics. The opportunity to draw in voices on this topic from outside the UK underscored the global and highly pressing nature of these issues. In his novel, Akbar takes square aim at the historical inequalities of India as expressed through the caste system, but also notes the class divisions, social exclusion and invisibility rampant within the U.K. The reality came as a shock to him when living in a poor area just outside Oxford, and only after his lack of middle-class, academic visitors, realised it was an area that no don would fear to tread. The walls in the city of his book are there to divide those from different castes from each other, which is a potent symbol for the hardening of social divisions worldwide.

The contrast between the pairing was useful, but also the parallels. Both authors agreed that embracing a multifaceted identity obfuscates those who, often including UK publishers, demand that people and things should fit into just one convenient category. Lord explained that the categorisation of genres for marketing purposes has thrown up a conundrum for Caribbean speculative fiction, and in a region where folklore is embedded into the culture, rigid categorisation can be both unrealistic and a limitation. Her own work has proved accessible to the mainstream, yet careful reading would uncover the multi-layered narrative that make it, as she said with a despairing sigh, “more than just a love story”.

Lisa Williams

Portraits of 21st Century Africa: Maimouna Jallow & Mara Menzies

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Spiegeltent, Charlotte Sq.

15thAugust

This was an event that Festival Director Nick Barley cared about enough to introduce and chair himself, which is, let’s face it, quite some recommendation. Nick told us about having seen these storytellers in Nigeria, and having been amazed by the reactions of the audience to one of Mara’s stories. He challenged us to outdo that audience in clapping, jumping out of our seats, shouting, and generally making an all-out whoop-de-doo. I’ll admit I cringed, I wanted to say “Nick, we’re Scots, we show our appreciation by rapt attention at best, and not throwing chairs at worst. That is unless we’ve aready had a wee swallae, ken.” This was the middle of the day, we were mainly middle-aged, mainly middle-class, and mainly sober. But, I have to admit, we did unlace our stays a wee bit. Hard not to, under the circumstances.

The Spiegeltent is not an easy venue. It is right next to the busiest of the roads that surround Charlotte Square Gardens, it is subject to the roar of traffic and, this afternoon, to the intermittent blare of emergency service sirens. Someone taking to the stage here has to be able to dazzle under pretty difficult circumstances. Neither Maimouna Jallow nor Mara Menzies had any difficulty dominating the stage, by appearing in personae. This was where a difficulty arose for me, with the question: can the ‘larger-than-life African woman’ now be taken as a stereotype? I suppose there is a danger of that. I felt that a way to plane the rough edges off that would have been if Maimouna and Mara could have operated from among us – as though we were a company around a fireside, or at a ceilidh in the traditional sense of the word, where people visit each other’s homes for the craic – rather than from the stage. Can this be done at the Book Festival? It’s certainly something to bear in mind. I would have felt a much greater connection with them, much less as though my bum was cemented to my chair and I was obliged to be a well-behaved audience member, no matter what Nick Barley said.

This whole entertainer/audience binary made me very much aware of cultural issues too. Neither Maimouna nor Mara was untouched by them either. The Festival blurb lists them as both being Kenyan; the ‘Biography’ section of Mara’s own web site lists her only as “one of Scotland’s best loved performance storytellers,” and Maimouna, though based in Nairobi, has Wolof and Spanish heritage, and both are aware that there is an extent to which they are showcasing traditional material from a step away from themselves. In an sense, they are collectors rather in the vein of Cecil Sharp, you could say. I was also aware of ‘liberal triggers’ in the material – why shouldn’t a woman inherit a house? if sex is unavoidable, why shouldn’t a woman use it as a kind of weapon? – and I’m sure I wasn’t alone in the audience.

But hey! What I really wanted to do was take my Postcolonial Studies hat off, give my cultural awareness a jubilee, forget about stereotypes, gender politics and such, and just kick back and enjoy being told stories. Was that a starter today? Well, yes. In skip-loads, actually. That should tell you how good these two women are. Both left me wanting more. If you should get the opportunity to see Maimouna’s stage adaptation of Lola Shoneyin’s novel The Secret Lives Of Baba Segi’s Wives, then do so. Keep your eyes peeled for Mara too – as she is based in Edinburgh that shouldn’t be too difficult. I’ll not say anything more about the content of their material, but rather I’ll leave it as a very pleasant surprise for you when you get to experience it for yourselves.

I would like to thank both storytellers sincerely, and to add a special, extra thank you. They had missed their photo call back in the media area, so after the event I asked Nick Barley if I could have a mini photo-call of my own. He said yes, and both Maimouna and Mara graciously agreed too. As a result, I managed to get the exclusive shots that accompany this review. Off-the-scale privilege.

Paul Thompson

Allan Little’s Big Interview: Kamal Ahmed

Edinburgh International Book Festival

12.8.18

Kamal Ahmed is the Economics editor of the BBC so I knew when I turned up for this event that I was in for some highbrow chat. As the talk was billed as ‘Has capitalism hit the buffers?’ I was also hoping for some answers. As a raving socialist I was on some level hoping for a polemical attack on late stage capitalism but of course I should have known better for this was a balanced nuanced discussion which never the less did in its own way provide satisfying answers to the question.

First off Little and Ahmed talked about a bit about the background to the current situation we find ourselves in explaining how Keynsian consensus was arrived at in the aftermath of WW2 and how until the 1970’s a balance existed between a mixed economy and a strong welfare state. The difficult period of strikes and power cuts in the 1970’s led to this breaking down and its replacement by the neo-liberal ideas of Milton Friedman and the Chicago school. This free market economic ideas led to Thatcher and Reagan whose attitude that the market will provide continued until the financial crash of 2008.

Ahmed pointed out that there have been other crashes since WW2 such as the Asian crash which is still effecting Japan today but acknowledged that 2008’s was a game-changer. The main difference Ahmed suggested was that the effect had been so devastating because the banks were now global. When challenged by Little on how the banks themselves had been effected Ahmed explained that there were in fact far greater controls on them than previously and that their balance sheets were drastically reduced. This meant also that they were risk averse which caused various problems. It means that they invest in fixed capital eg properties rather than other types e.g. new businesses causing people’s incomes to drop and remain low. It became apparent that Ahmed himself was not in any sense an anti-capitalist. He suggested that capitalism had been a positive force in emerging economies in South Asia allowing many citizens to rise out of poverty. He was however concerned that China’s successes demonstrated that capitalism’s previous interconnected relationship with democracy was crumbling. He felt that the technological behemoths of corporations such as Amazon and Google were also doing much to destroy notions of accountability and fair practice.

Ahmed felt that capitalism was failing in its central promise of rewarding those who work hard and ‘play the game’ He recognised that Millennials have a very different more cynical attitude to the older generations with regards to the capitalist consensus and that if Capitalism was to remain relevant it would have to change. He suggested that in the 21st century people wanted ‘a democracy you could touch’ and that he saw a return to localism combined with a kind of loose global policing of big business as a plausible way forward.

The discussion then went on to explore recent changes in attitude to the way the general public consume and relate to the media. Little challenged Ahmed about the erosion of trust in the BBC something which he met head on. Ahmed felt that it was important to retain a sense of balance but acknowledged the difficulties of this in a more polarised world. He felt that ultimately the BBC needed to be rigorous in all areas and non-partisan and that all sides should be treated with the same level of scrutiny. He suggested that this did not necessarily mean always having balance as he had to ultimately make a judgement call based on where he felt the truth lay. This he suggested was based on trusting the findings of experts and by being data led. He felt that the polarised binary way in which Brexit was reported was unhelpful and that he s aught to be direct and straight forward in his approach. He was interested in modernising news and current affairs in a way which recognised the different way people now consume news whilst also acknowledging that the disconnect the media creates between itself and people’s real lives has made it hard for them to trust.

This was a nuanced, intelligent discussion which certainly provided much for me to process and reflect upon – a far cry from the hectoring sloganeering of much of today’s media discussion.

Ian Pepper

Freedom Debate: Commonwealth The Legacy of Empire

Chaired by Australian Julianne Schultz the panel that gathered to discuss the role of the Commonwealth had three panellists, from India, Ghana and Barbados who collectively brought an awe-inspiring range of talent and experience to the table. Schultz herself is a prolific author and editor of quarterly journal, the Griffith Review. The panelists included Karen Lord, a Barbadian polymath and author of multi-award-winning Redemptive in Indigo, Best of all Possible Worlds and the Galaxy Game, Margaret Busby, the legendary writer, editor and broadcaster who became Britain’s youngest and first Black woman publisher and Salil Tripathi, Indian-born human rights journalist and author, currently based in London and Chair of the Writers in Prison Committee of PEN International. The very existence of the Commonwealth is, of course, contentious and a ripe subject for discussion. First mooted by Scottish aristocrat Lord Rosebury in 1884 as a means of keeping ex-colonies as allies after decolonisation, the Commonwealth was created in 1926. Potential British hopes for a post-Brexit Empire 2.0 were scrutinised, as symbolised in Meghan Markle’s elaborately embroidered wedding veil. This kicked off a broad discussion of many issues; including the appropriateness of inherited succession to the post of Head of the Commonwealth, and questions of how Commonwealth countries can best work together.

The relative importance to the speakers of the Commonwealth in the past was influenced by age, national history and the process of independence creating significant variations in experience. All the speakers agreed on the importance of understanding the history of the Commonwealth in order for us all to have a better understanding of issues of past and present immigration. Tripathi’s personal relationship had been a positive one, with fond memories of growing up in India with access to the British Council, British literature and most importantly, scholarships to study in Britain. However, the audience laughed at him likening Brexit to leaving a wife for an old flame; realising too late that life has moved on without you. Economies like India’s have certainly forged ahead in the meantime, surpassing Britain’s in 2016. Busby spoke of being born in Ghana in 1944 as British citizen, under the broader citizenship laws that were in place at the time, and the effect of being introduced to a narrow range of British literature at her British school. Lord shared the story that although she was born in an independent Barbados and studied a more relevant Caribbean syllabus, it was still a surprise to hear International Finance professors at Oxford freely admit that trade policies post-Independence were certainly not set up to benefit the ex-colonies in any way.

Lord used the example of a scene in George Lamming’s classic Barbadian novel, the Castle of my Skin where the disbelief at an elderly woman claiming to have been born a slave, parallels our current amnesia around our often fractious and violent history. She briefly touched on the history of independence for Caribbean countries and Britain’s selfish motivations for swift decolonisation. It would have been fruitful to tease out further how the method of granting of independence to Caribbean nations cemented individual national identities, interests of the local ruling classes and international capital.

There was, however, much discussion of the unfairness and the devastating psychological impact of the recent Windrush debacle that finally hit the headlines in 2018, particularly by Busby. Rightly so, as we need to continue the pressure to resolve the myriad cases of Caribbean-born, legal British citizens brought to Britain as children on a British passport who have suddenly been denied citizenship or even the right to enter the country from a trip abroad. Busby was keen to emphasise that Britain needs a fuller understanding of the Commonwealth in order to recognise the contribution by immigrants to Britain from ex-colonies, from creating, expanding and supporting the national economy to the many and varied contributions to national culture. There was general agreement that the British education system is severely narrow and limited in its focus which doesn’t provide the necessary context for understanding a demand for reparations, economically or otherwise. The issue of reparations is a touchy subject, that our political leaders make a point of dodging. From Tony Blair’s refusal of an outright apology over slavery in 2007, to David Cameron sidestepping all discussions of reparations on his ‘prison debacle’ visit to Jamaica in 2015. In the absence of a richer educational curriculum, ignorance can contribute to alienation. Tripathi cited the example of the whitewashing of the fuller historical narrative, citing the recent film Dunkirk as an example of omitting the contributions of non-white soldiers from around the world in various war efforts. Lord suggested that this kind of historical ignorance often leads to blaming others for their own misfortunes or seeming lack of progress.

One of the potential benefits of cooperating with other Commonwealth countries is the ease of communication through a mutual language, but this also comes loaded with its own problems. One of the benefits of writing in English is that literature can be more easily promoted and reach a wider global audience. Tagore’s work, for example, once it was translated into English by a passionate Yeats, went global. Even the insistence on English for entrants in the Commonwealth Writers Prize, gives a huge headstart in the race to native English speakers. Issues of language and how it affects identity and the expression of one’s authentic self have been debated among Caribbean writers for years. Lord outlined the debates over the use of Standard English or national dialects in Caribbean writing, including the perception and accessibility of dialect, particularly French patois and Amerindian languages used in Guyana.

Tripathi considered the most useful role of the Commonwealth could be in the area of human rights, citing examples of times when Pakistan and Nigeria have been asked to leave over these issues. The panel agreed on the great possibilities of South-South cooperation, particularly in sharing culture to facilitate debate. I was interested in what the panel considered the most urgent but practical issues should in the huge topic of reparations, but there wasn’t time to go beyond the immediate issue of righting the wrongs of the Windrush scandal. In an era of complicated trade agreements, the stranglehold of the IMF, using the Commonwealth to strengthen South-South trade is perhaps idealistic. However, with the global growth of publishing houses, perhaps the publishing industry can tentatively lead the way.

Lisa Williams

EIBF: Carol Ann Duffy with Keith Hutson & Mark Pajak

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Baillie Gifford Main Theatre

14thAugust

Carol Ann Duffy doesn’t smile much, one never knows how to take her. So when it was announced at the beginning of the event that there would be no question-and-answer session at the end, and that the poets who were taking to the stage had asked us not to tweet during the performance, there was that kind of hush you get when everyone wonders whether this was going to be a po-faced afternoon. As it turned out, there was no need to worry at all, because it was a sheer delight from beginning to end, so much so that the hour went by in what seemed to be the proverbial twinkling of an eye.

Carol Ann has an ongoing policy of seeking out relatively unknown, emerging poets and championing them. The presentation today included two of her latest protégés, Mark Pajak and Keith Hutson. Neither of them had ever appeared in a Book Festival event before – Mark said he had been here as a punter – and when I asked them afterwards how it felt now it was all over, they both testified to the adrenalin still working. You wouldn’t have known that they were anything other than totally relaxed from how they came across in front of the audience; this isn’t really all that surprising, as they had both given readings before, that much is obvious.

Mark Pajak is a Liverpudlian. He has a careful, lilting delivery which – he won’t thank me for this – reminds me a lot of Roger McGough. I know, such comparisons are inevitable whenever a poet from Liverpool appears. In Mark’s case there is something about the timbre of his voice and in the questioning inflection at the end of lines that evokes this. It is a style of delivery that captures and holds the attention, however, and it makes an audience hang on his every word. There is a lot of humour in his work, and a lot of tenderness. His account, a love poem if you will, of a stupid prank that he and the best friend of his childhood and youth carried out, and how it led on to the rest of their lives was… all right, I’ll say it… one of the most wonderful expressions of friendship since Edward Elgar wrote ‘Nimrod’. Over the top – moi? I’m being honest here, it was a Scouse David-and-Jonathan thing.

Keith Hutson was either born in Lancashire and lives in Yorkshire, or vice-versa. Anyhow, the Roses cricket matches must be hell for him! In contrast to Mark, Keith delivers his poetry and the intervening patter with a broad if imperfect grin. One tooth is missing. “You should see the other poet. All I said was don’t give up the day job!” His speciality is the celebration of bygone stars and meteors of the music hall and variety. His subjects ranged from an impresario who, after a walk-out by his whole cast, performed solo on stage every character in the story of Dick Turpin, to bandleader Ivy Benson and the resentment directed her as an outstanding female in a male world, to railway-obsessed, RADA-trained (hah!) Reginald Gardiner. I think Keith was tickled when, afterwards, I said “Reginald Gardiner – that’s the ‘biddly-dee, biddly-dah’ man, right?” Readers, that’ll only mean something to my generation, people who remember ‘Uncle Mac’ on the radio on Saturday mornings!

Carol Ann bracketed the event. She flagged up the humour of the event by opening with her short poem about encountering a gorilla at Berlin Zoo; they stare each other out, the gorilla’s gaze barely concealing rage – “with a day’s more evolution, it could even be President.” Okay, well-judged there, she took a chance that a certain politician currently prominent on the world stage is not popular in his ancestral country and it paid off. Her finishing poem was a sestina. Carol Ann can do this, she can bend old poetic forms to her will. This sestina depended on the repetition of six words (of course): arseholes, gatekeepers, chancers, tossers, bullshitters, and patriots. In passing, I wonder if, when she first wrote that poem, she speculated beforehand which of those six words spellcheck was going to reject, and whether she experimented just to see whether her computer would accept the American spelling of ‘arsehole’. Anyway, that’s hardly relevant, because her sestina wove those words and several homophones round themselves like the patterning on a Fair Isle jumper. I confess that I have never been her greatest fan, but reviewing a reading by her and, as is necessary in a good review, leaving my prejudices outside, I can say that I now see precisely why she was awarded the Laureate. Applause.

Overall, this was a splendid event to start of my personal tour of duty at Charlotte Square – thank you, Book Festival – but as always it felt much too short. I know, that can’t be helped.

Paul Thompson

EIBF: Rose McGowan with Afua Hirsch

Edinburgh International Book Festival

13.8.18

If any of you are for some bizarre reason unaware of who Rose McGowan is at this stage then its time to be introduced. McGowan was until recently mainly known as an actor, appearing in independent movies but also toying with the majors in films such as “Scream” and the successful TV show “Charmed”. All that changed though last year though when she became a Hollywood whistle-blower with regards to the sexual abuse prevalent in the film industry. Her courage in doing this helped to bring down Harvey Weinstein, one of Hollywood’s biggest players as well as encouraging other women to come forward with their own experiences kick-starting the ‘#MeToo movement’. But you knew all that already – unless that is you’ve been hiding under a rock for the last year. What you might not be aware of is that McGowan is now also an author and was here at the book festival to promote her autobiography, “Brave”. It was clear from the start of the interview that Afua Hirsch herself is something of a fan so I was concerned this was going to be a rather fawning affair – the acolyte stroking the ego of the glamorous movie star. Yet from the very beginning it was apparent that McGowan was not that kind of actor. Giving us a reading from the introduction to her book it became clear that her journey from Hollywood starlet to social justice warrior was complex and owed much to the harsh lessons of her early life.

McGowan described how her upbringing in a religious cult, “The Children of God” led her to have direct early experiences in the abuse of power which she feels is also so prevalent in Hollywood. She described how she feels the use of trigger words, punishments and similar cult techniques are used not only in Hollywood but also in the politics of Trump. In fact it was Trump’s election that encouraged her to contact the press to break her story early ( she was already writing the book). Sick of seeing the rise of sexism and racism his presidency seemed to foster she felt it was the right time to speak out. McGowan mentioned almost casually that when she was attacked by Weinstein she told people right away but was ignored or dismissed. Feeling voiceless she essentially just ploughed on with her work trying to distance herself from the culture of Hollywood whilst remaining working within it, an experience she described as being “a lonely road”.

Whilst working on her book and when she started to talk openly about her experiences she began to be hacked, stalked and spied on, an experience which has in part led her to selling her Hollywood home and living out of a suitcase. As she describes it “Hollywood acts like the mafia to protect its own’. This did not silence her however but merely encouraged her in the belief that she was doing the right thing. This steely resolve is clearly at the core of her as is a sharp self-aware intelligence which is critical of her own previous inability to see the warning signs of threat and danger in her early days in the industry. A former teenage runaway with ‘street smarts’ she could only put it down to being overwhelmed by the oily charm of ‘people who were not my people’. McGowan acknowledged that the last year has been tough on her and that “the stress of it almost snapped me’ but that it was fantastic that so many people were now coming forward to tell their own stories. When questioned if she had any inkling as to how big this would become she said that she didn’t think about it at all, that she just needed to act in order to as she put it “make it impossible to look away”.

The roots of the abuse she feels run very deep indeed and she described the serial abuse of aspiring starlets in the 1920’s as being not the casting couch but “the rape couch”. She described how she has been forced to look back over some of her early sexual experiences within Tinseltown in a new light as the molestations that they really were. Far from being merely an issue within the industry she feels that if women look back over their own lives they too will recognise this.

McGowan expressed her feeling that Hollywood holds a ‘fucked up mirror’ for all of us to gaze within and shows us a distorted image of the world which is damaging to both men and women alike. She feels that it is important for all of us to be self aware and critical of the culture we live within and be conscious that “what you have consumed from birth has formed you”. She feels that the images of women in much Hollywood product have a toxic effect on self identity and self esteem saying that “the men who thought they owned me think they own you too” This could all risk sounding a little hypocritical coming from an actor involved in the movie making machine itself but in fairness to McGowan she has remained mainly in independent cinema and been canny about her choices ( ‘Charmed’ being the longest running female led show in network history). She also is quick to point out how difficult this is admitting to loving ‘classic movies’ herself.

McGowan sees herself as essentially an optimistic person, and believes that Trump is in a sense an enabler of the kind of radicalism she espouses. She has no fear of offending and admits that to an extent it has cost her a more conventional creative career but believes that “being well behaved was not working in our favour”. By the end of the talk I was a fully paid up member of the Rose Army and would have happily taken the Queen’s shilling to do battle on her behalf. She was an eloquent, passionate and bracingly honest speaker who’s courage in speaking out against one of the most rich and powerful industries in the world has given us all encouragement to challenge corruption where we find it. Long may she reign.

Ian Pepper

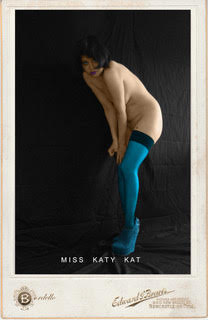

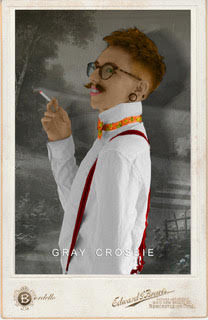

Poetry Bordello

August: 9th & 16th

Woodland Creatures (20.00)

The lovely thing about the night was that it was poetry – funny sexy, erotic, friendly poetry. The poetry the Ladies performed was of exceptional quality. Classy, twenty-something poems of love, & about lovers, including a sonnet to well-used and loved vibrators. There were thin poets, fat poets, beautiful lesbians, drag kings, & also Rosie Garland from my beloved Yorkshire, looking splendid in Whitby Vampire Clothes & incanting her muse to perfection.

All of the night’s poets were fantastic and all of them beautiful. To the mix were added two burlesque acts that were so bad, they were brilliant. Of these we witnessed Andromeda Mystik’s performance art, that really makes one think. I saw Andromeda perform her burlesque act at last years Fringe, I didnae get it then. But last night the penny finally dropped.

There’s a lot of visual and physical poetry being expressed on the burlesque stage right now, and the presence of physical performers in a spoken word gig is very inspirational to poets and encourages them to explore their own range of movements and visual appearances.

Read the full interview

All in all, it was a whirlwind hour in the quaintly titled Woodland Creatures pub. The performance space was like walking into a bohemian Parisian boudoir; sultrily lit, wooden pews, with a small stage on which a piano resides. Our host, Max Scratchman, the only Male performer of the evening also recited a newly crafted poem about love and the etiquette of love making. This was a top hour of entertainment and my word there is a lot to take in. The next Poetry Bordello is on the 16th August, so book your tickets soon, its going to be a sell-out.

Mark ‘Divine’ Calvert

————————————————————-

Poetry Bordello

Max Scratchman. (Host)

Andromeda Mystik. Performance art.

Carla Woodburn. Poet.

Katy Kat. Poet.

AR Crow. Poet.

Suky Goodfellow. Poet.

Angie Stachan, Poet.

Jo Gilbert. Poet.

Elizabeth McGeowan. Poet.

Taylor Swift, 666. Performance Art.

Rosie Garland. Poet.

An Interview with Max Scratchmann

The illustrious Max Scratchmann, parvenu extraordinaire, is bringing a bevvy of beauty & talent to Leith Walk this Fringe. The Mumble managed a wee blether…

Hello Max, so where ya from & where ya at, geographically speaking?

Max: I currently live in Edinburgh but I was born in India as part of the huge ex-pat Scottish community who worked in the jute mills there and brought “home” when I was six. I’ve since lived all over the Untied Kingdom from London to Orkney and I settled in Edinburgh seven years ago when I totally fell in love with the city.

Which poets inspire you, both old skool & today?

Max: I have very catholic taste in poetry and the people I read tend to range from Poe to Pam Ayres. I’m a great fan of the late 19th and early 20th century nonsense writers, like Edward Lear, Hilaire Belloc and Harry Graham – and of course the iconic Victorian to Edwardian female poets like Christian Rossetti, Emily Bronte and the absolutely stunning and underrated Charlotte Mew. Contemporary poet wise, most of the people I admire tend to be featured in my shows, since when I find a poet or performer who inspires me I stalk them until they agree to take part in a Poetry Circus gig. It’s hard to single any one poet out, they’re all so good, but I’ll make a quick mention of our two fantastic headliners, Rosie Garland and Elise Hadgraft, who really push poetry to the furthest realms of its borders and use words in ways that even cynical old grumps like me find themselves amazed by.

You have traveled to, & perform’d in, events all over Scotland. How do you find the Scottish poetry scene?

Max: Poetry ‘scenes’ differ from country to country and even city to city, but the Scottish scene is particularly imaginative and vibrant right now. Rana Marathon is doing wonders in Perth; Glasgow is flourishing with Sam Small and Kevin Gilday & Cat Hepburn putting on regular nights; and though we’ve lost Blind Poetics and Soap Box here in Edinburgh there’s still Inky Fingers, the Goddamn Slam, Loud Poets and, of course, new girl Jacqueline Whymark’s runaway success, From the Horse’s Mouth.

Can you tell us about Poetry Circus?

Max: Yes. Poetry Circus started way back in 2014 after a chance meeting between myself and the dancer/poet, Josie Pizer, at a writers’ workshop. We had both been bemoaning the lack of theatre in poetry gigs, and the tendency of some poets to stand hiding behind the mic with their nose buried in their very expensive Paperchase note book, mumbling what was often really good poetry. What we really wanted to see was more visually stunning work, and more of poets who could demonstrate a big personality on stage. We were also particularly keen on ‘poetry’ that was expressed with more than just words, and, before we quite knew what had hit us we’d formed a spoken word theatre company and, over the last four years, we’ve hosted dancers, performance artists and film-makers under our all-encompassing banner of poetry.

What does Max Scratchmann like to do when he’s not being creative?

Max: I think I’m always being creative. In addition to my writing and performance work I’m also a visual artist & animator and an occasional tutor and workshop facilitator, plus I find time to be an artist’s model and – currently – a living sculpture in an art installation.

You are stranded on a desert island with three good books. What would they be?

Max: They would have to be very long books that could stand re-reading! I’d have to say The DANNY Quadrilogy by Chancery Stone; Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie and the complete works of Kirsty Logan. What would really be better though would be a perpetual library card and mobile library that was driven by passing dolphins…

You’re about to shoot the meteor of dazzling wordplay that is Poetry Bordello back into the Fringe’s poetical stratosphere, how did you get involved & are you excited to be back?

Max: Because a lot of my personal work is comedic I’m quite heavily in demand for cabarets – particularly during the Fringe – and, as such, i became very intensively involved in the burlesque scene a couple of years ago and was blown away by some of the performers and performance artists on that stage. It occurred to me that a lot of burlesque acts were visual poetry and lots of the artists make statements on important issues like gender politics and personal sexuality, so from there it was only a short hop towards inviting burlesque performers to join the Poetry Circus regulars, and the chemistry that we’ve discovered between the artistes is electric.

Can you tell us more about Poetry Bordello?

Max: Poetry Bordello is a unique show because it fuses physical performance art and burlesque with spoken word and poetry and provides a safe space for poets to perform their more personal work on themes of sexuality, gender and personality in a supportive environment. Plus they get to dress up if they want to!

Who is the MC & is she any good?

Max: Because we’re running a Bordello we really needed a Madam, and we found the ideal one in the shape of our very own Madam Isla. Bearing a passing resemblance to the outstanding stand-up comedian, Isla Maclean, Madam Isla will steer you into the shady underworld of the Bordello and ensure that you have an amazing time. And, yes, of course she’s good…

What acts have you got for us this year?

Max: We’re totally thrilled to be presenting bestselling novelist and chanteuse Rosie Garland headlining on 9th August, and Elise Hadgraft aka Corporationpop on 16th August before she heads off to Berlin to start a world tour with her new punk band; plus a mouthwatering array of slam-busting performance poets including the Belfast Slam Champion, Elizabeth McGeown, Imogen Stirling, Gray Crosbie, Max Scratchmann, AR Crow, this year’s Stanza Slam Champ, Jo Gilbert, Suky Goodfellow, Orla – Sparklechops – Kelly, Katy Kat, Express Yourself’s Carla Woodburn and the poet laureate of Aldi, our very own Angie Strachan; plus we’re super chuffed to be welcoming back the renowned sideshow dancer and choreographer, Andromada Mystic, from Sanctuary of Sin plus astounding physical performers Taylor Swift 666 and Sharrow.

Why do you think the blend of spoken word & burlesque works so well – especially in the hands of Poetry Bordello?

Max: As I’ve said, there’s a lot of visual and physical poetry being expressed on the burlesque stage right now, and the presence of physical performers in a spoken word gig is very inspirational to poets and encourages them to explore their own range of movements and visual appearances. We’ve been doing a series of photoshoots over the last few weeks, using the themes of bordellos and Edwardian music halls, and in particular the photography of E J Bellocq, and the performers have been pushing their own limits and have a whale of a time.

What do you think the audience will take away from the performances?

Max: Hopefully, they’ll have a totally amazing time but also find themselves thinking about some of the themes raised and maybe want to rethink their own attitudes on gender stereotypes and sexual labelling.

You’ve got 20 seconds to sell the show in the street, what do you say?

Max: Did you really, really hate poetry when you were at school? You’ll love this.

What will Max Scratchmann be doing after the Fringe?

Max: I’ll be producing a new show called Speakin’ Cajun with the Jennifer Ewan Band at the Traverse Theatre on 22nd September (and we’re doing a shorter Fringe version at Woodland Creatures on 22nd and 23rd August); plus I’ll be touring and appearing in cabarets and hopefully finishing my latest book of short fiction.

Poetry Bordello

August: 9th & 16th

Woodland Creatures (20.00)

www.facebook.com/poetrycircusevents

An Interview with Lily Asch

Real Talk is both a hugely beneficial social enterprise & the fertile bedsoil of a right good yarn. The Mumble caught its founder for a wee blether…

Hello Lily, so where ya from & where ya at, geographically speaking?

Lily: So I’m originally from Connecticut in the USA. I moved to Edinburgh when I was 20 and have been here for the past 5 years and it has become home to me.

When did you first realise you could tell a good story?

Lily: From a very young age I was enraptured with reading, consuming anything I could get my hands on particularly fairytales and high fantasy. I think that this early immersion in story made me naturally inclined to want to tell and share the stories I learned. My Mom constantly reminds me how I’d regale my family with minute details of my day each night at dinner (whether or not the audience was that interested). However it wasn’t until I got involved with theatre at age 9 that I really honed the more performative element of sharing. While I only acted for a few years, I think those foundational telling skills have stuck with me. So it has been a journey from loving to tell to actually developing my craft and I’m presently doing my storytelling apprenticeship at the Scottish Storytelling Centre and am a part of TellYours2018, a development programme for the next generation of UK storytellers.

You are stranded on a desert island with three good books. What would they be?

Lily: Oh my, this is really hard because quite a few of my favourite books are a part of a series… If I’m being cheeky I might bring along the entire His Dark Materials Series by Phillip Pullman in one book (which does exist because I have it). I’d bring along The Door by Magda Szabo, there is something haunting about it that makes me want to read it again and again, and then lastly the entire anthology of Grimm’s fairytales for a bit of variety :]

We are here to talk about an event of yours later this week, under the Real Talk banner. Can you tell us about the organisation?

Lily: So Real Talk is a mental health storytelling social enterprise. Our vision is world that celebrates transparency and authenticity around experiences of mental ill health and actively supports wellbeing. In practice we support people who have experienced mental ill health to learn how to share stories about their lives. We have a process where we deliver two workshops that use traditional storytelling tools to help participants craft a 10 minute story. After these 2 workshops we host a community event where these stories are shared to an audience and used as an entry point to speak about mental health more widely. We’ve found the process and these events really cultivate compassion for oneself and for others.

How did you get involved?

Lily: So I’m actually the founder of Real Talk. It was born out of my own experiences with mental illness and realising the need for more safe spaces for people to talk about their mental health and for other people to listen. It started as a passion project in 2016 and over the past 2 years I’ve been slowly transitioning to working on Real Talk full time. It has been quite challenging starting up a social enterprise but also so rewarding. I’ve met hundreds of people all looking to connect about mental health and excited about the power of stories. You can learn more at www.realtalkproject.org.

I can imagine there are some emotional moments involved. Do the storytellers find it a cathartic experience or is it sometimes too much?

Lily: There are definitely some deeply emotional moments along the process. There is catharsis in sharing a bit of yourself to an audience, empowerment in being to share your story in your own words but of course the nerves and tentativeness that comes from acts of vulnerability. I think this is where the process is really important, storytelling as a creative practice is a wonderful vehicle for holding people where they are. However we always emphasise that participation is voluntary (so if people don’t want to complete the process they don’t have to) and I hold a COSCA Counselling Skills certificate and Mental Health First Aid training so am always on hand to help signpost to further support if needed.

Can you tell us about the event at the Scottish Storytelling Centre?

Lily: On Friday the 27th of July at 7.30pm, we will be hosting one of our community storytelling sessions. 7 participants will have come through the process and will be sharing 10 minute stories to a public audience. After all the stories are shared I’ll facilitate breakout discussion between the audience members before ending with an informal Q & A between the storytellers and the audience. We’ve run 11 events to date and they are always magical evenings where people come together to witness each other.

How much experience do the storytellers have?

Lily: Most of the tellers have very limited storytelling experience in a performative way, though some people definitely have experience with public speaking. For some it’s actually their first time sharing a part of their story in this way. It’s a big range but that is exactly why we have this preparatory process, so everyone has had a space to decide what story they feel comfortable sharing and how they want to do it. I’m always humbled by the creativity, bravery and strength of each speaker, even if they don’t see it in themselves.

What do you think the audience will take away from hearing the stories?

What do you think the audience will take away from hearing the stories?

Lily: Insight, emotion, resonance, clarity, empathy. Because the audiences are diverse, everyone takes away something different but I think that having genuine insight into someone’s lived experience really breaks down stigma and barriers. Some are supporting a loved one who is suffering, so to hearing a real story helps them know how to help. Others might be suffering themselves and the power of realising you aren’t alone in your journey cannot be understated. Others are just curious and we hold safe space to talk about mental health openly, which we don’t always feel allowed to do during our day-to-day lives.

What does the rest of 2018 hold in store for both yourself & Real Talk

Lily: The rest of 2018 hold incredible potential! I’ll be working away at building Real Talk’s foundation as a social enterprise; building a team to help run it and expanding our event series. Hopefully we’ll be collaborating with other awesome organisations and supporting more people (feel free to get in touch!). Personally I’m hoping to graduate from my storytelling apprenticeship this year and start working as a traditional storyteller out with my work with Real Talk.

Real Talk: Story For Well Being

Friday, July 27th

Scottish Storytelling Centre

Tweets by @realtalkstories

www.realtalkproject.org

Don’t be afraid; art is for all.

How to get the most out of your gallery visit

How do you feel about visiting an art gallery? Do you go for pleasure, for education, self-improvement or to socialise? Or do you avoid them and feel that art is just not for you? Many people feel uncomfortable just stepping over the threshold of a gallery, whether it’s a huge and majestic Victorian building or a temporary white box as cutting edge as they come. Maybe you just nip in for some quality cake and a clean loo?

If it’s pleasure; at the appreciation of human-made beauty, the vision and talent in expressing it to us, the viewers, does the act of viewing the art actually engender a feeling of joy inside you? Can you express that joy in an environment where you’re frightened your shoes will make too much noise on the ancient marble floor? This may come more easily to the introverts among you, savouring the silence and opportunity to have your own private encounter with a beautiful painting and the mind of the artist. What about the extroverts among you? Can you express that joy when you’re trying to quietly cross that marble floor or tentatively pad across the carpet? Perhaps you’ve gone for self-improvement purposes. If so, it could be a little easier to gain some satisfaction from spending your precious time, as you add to your bank of cultural capital. Or you might simply appreciate the respite from a frantic life; a chance to feel solemn, silent and dutiful, like in a Presbyterian church or libraries of old.

Or do you prefer the ‘cocktail party’ setting of a smaller gallery, and relish jumping into the intellectual debate with passionate, quirky artists discussing cutting edge contemporary art? Or do you worry that you don’t quite understand, that commenting at all will mean missing the mark with an inane comment, or worse, unwittingly become part of an experimental performance piece? Does it feel like forced intimacy, standing awkwardly with your wine glass at smaller events, where you feel expected to say something worth ransacking the smaller, more homely silence of a white-walled box? Uneasy at a sense that the artists might be observing you observing their thoughts made manifest. Do most of us realise the extent to which we have been trained to behave in prescribed and acceptable ways as we enter these environments?

http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/articles/white-cube-and-beyond

I’m just as ambivalent about children making noise in libraries as in art galleries. I want to hush noisy children so I can concentrate on reading in our shared space, but perhaps I’m only resenting their freedom because we had to be quiet, back in our day. I’m glad they feel free enough to express themselves; perhaps they’re part of a budding, enthusiastic pre-school book group. Just not when I’m there. I relate to their childlike state in a way, as I seem to have something resembling a middle-aged onset of ADHD, where sitting still or concentrating for long periods is difficult, but I generally manage for others’ sake. I can’t bring myself to raise more than a whisper in a library, but, bloody hell, in other settings, I want to join in with the conversation, in an almost ‘repressed Tourette’s’ type way. I want everyone to join in. If I’m honest, generally I want all hell to break loose and it to become one big carnival. Politeness and shyness merge with bourgeois norms of behaviour in high arts settings, hell, even cinemas, and it drives me to distraction. British audiences are expected to refrain from moving their bodies or making any noise during a play, except for polite applause or perhaps a hastily wiped tear. Partly because in an urban setting, the audience are the maligned or tolerated ‘public’, rather than friends and acquaintances, and the British are still the last nation on earth to embrace a messy and unnecessary display of emotions. Unless it’s splashed across a wall or screen or stage and safely at a distance. Perhaps the tots in the library are leading the way forward after all.

We seem to edging back toward the boisterous interaction of Shakespeare’s audiences in theatre settings, and it’s becoming increasingly acceptable, even necessary, in visual art environments. Accompanying a school group to the National Gallery is much more engaging and fun than going alone. I learned more about the secret symbols embedded in paintings in an hour than I have in years. We could take over the space and not worry about annoying anyone else or depriving someone more deserving of the leather couch. If art galleries went the way of museums with hands-on activities, even for adults, or just meeting or watching artists at work it would make you feel part of the place and stay for longer. There’s a wee gem of an exhibition currently showing at the oft-overlooked Inverleith House in Edinburgh’s Botanical Gadens; yet another collaboration of poetry and art that both delights the senses and delivers an deep message. The gallery space is warm and welcoming for all ages, this time with quiet opportunities for children to allow nature to inspire their creativity.

There are huge debates about why certain ‘demographics’ are less likely to visit British art galleries. Mostly between people who are not from ‘those demographics’, who, in awkward terms, display some imaginative ideas of what, for them, constitutes ‘the other’. Some of it is simply a ‘perception problem’, that art galleries are for the white and middle-class, and indeed, there is often a very real psychological discomfort for certain people in places that are not, perhaps in small but significant ways, welcoming to all. Women artists, working-class artists and artists of colour are still underrepresented, marginalized and ‘othered’ by curators and board members who are not from these backgrounds, partly because of the narrow understanding that results from stultifyingly homogeneous social and professional networks. As talented artists and their works suffer unduly from the lack of exposure that they deserve, whether through tokenism, pigeonholing or downright exclusion, some important conversations about history and society are also being omitted from the mainstream art world. The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s idea of ‘cultural capital’ is often used to explain why the intellectual elite, reared on a steady diet of high art from childhood, frequent and feel at home in high art institutions, which generally cater to their particular interests. Content, and how and by whom the content is curated, of course, can also be key, and is currently the subject of heated debates. http://www.voice-online.co.uk/article/black-people-dont-go-art-galleries.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/may/04/baltimore-museum-art-warhol-artists-of-colour

With major prizes going to women artists of colour recently, notably, Lubaina Humid’s 2017 Turner Prize win, and Barbadian-born, Glasgow-based artist Alberta Whittle claiming the 2018 Margaret Tait award, this no doubt encouraged the new director of Glasgow International to hold a variety of exhibitions, talks and performances by artists of colour. This was particularly welcome in the wake of Transmission’s Gallery’s funding recently being unceremoniously cut by Creative Scotland. The decision was made despite Transmission receiving high acclaim for their work and social impact by the very same organisation. The artist-run institution, founded by Glasgow artists in 1983, has continued in its radical tradition to encourage important conversations, particularly around Black art and artists, gender and sexuality; pushing boundaries and inspiring new ways of thinking. One of these artists is Camara Taylor, exhibiting at GI this year. Seeing as this is exactly the raison d’être of contemporary art, this has been a massive blow to both the artists and Scotland’s modern art scene. https://frieze.com/article/why-did-creative-scotland-defund-storied-glasgow-art-gallery-transmission

One of the exhibitions I attended at Glasgow International was ‘(BUT)..WHAT ARE YOU DOING ABOUT WHITE SUPREMACY? which included powerful live performances to a rapt, multiracial audience. https://manystudios.co.uk/syfu/ Sometimes the conversations that result might be unsettling for some people forced to reflect on and reframe some of their most cherished or simply unconscious beliefs about their own history and identity, but that’s precisely why art must make space for them.

The fear of ‘wasting time’, is a real one. Whether you’re hustling on the breadline, trying to make ends meet with three dead end jobs, or hustling as a CEO of an investment bank, the risk of wasting time aimlessly wandering around a gallery that doesn’t immediately serve your needs, is not one you are going to take. Even the visitors don’t like to waste too much time. Various studies have shown the average visitor spends 30 seconds in front of a painting, perhaps a masterpiece that has taken decades to complete, with careful patronage from a house of aristocrats or royalty. It’s rather like gobbling up a beautifully cooked and arranged dinner in 5 minutes flat. But, hey, don’t stay there just because you feel you should. The gallery will be gaining extra points for a steady stream of punters anyway. But why might you want to go to a gallery in the first place? What do you expect to gain from going? Seeing as most other arts, from novels to songs, involve story-telling of some kind, perhaps the emotional connection can’t be had easily without knowing something of the back story. Of the artists, the time, the place, the emotional state they were in during the period of creation and who else and what else they may have been responding to. I’ve been doing some research into Scottish historical figures and how their personal stories relate to wider themes, and it’s been exciting to spot them in both the National Portrait Gallery and the National Gallery, and realising how just how limited and misleading the information plaques very often are.

Big galleries are free, open, not demanding of a special invitation. You can stay as long as you like. In theory, it is entirely democratic, as it’s yours to share during opening hours. Yet, for many people, it doesn’t feel that way. The National Gallery in London changed their stairs at their entrance because apparently people found them intimidating. Do you like the majesty of columns and chandeliers or does going into these buildings, with architecture that stems from a tradition of an entrenched class structure, make you feel like you don’t belong there? Temples all over the world have stairs. Even the Christ statue in Rio has 220 steps… Ordinary people make the pilgrimage. Yet how familiar might we find the surroundings, let alone the people, of Oxford University if we haven’t gone to a top public school? How at home might we feel in the Houses of Parliament? The Vatican? Do we need to feel a sense of belonging? Does the beauty elevate us or oppress us? Edinburgh is well known for its snobbery, and tribal groupings easily coalesce around ‘low’ and ‘high’ art. Neu Reekie! is a local arts organisation that loves to mess with this dichotomy, and enjoys taking over otherwise solemn spaces like the National Galleries with an irreverent mix of poetry, music and animation, creating an atmosphere that’s a little freer. http://www.theskinny.co.uk/books/events/neu-reekie-does-titian-national-gallery-of-scotland

Collective (www.collectivegallery.net), a contemporary art gallery that’s been based in Edinburgh since 1984, has recently made the heights of Calton Hill its new home. It states emphatically that a major part of its mission is to be the friendly face of contemporary art precisely in order to encourage dialogue. Accessibility is its watch word; extending itself to offer an experience welcoming to all, adapting the trails to the site and the exhibitions to accommodate visitors who are blind or partially-sighted. I’m sure with advances in technology, visiting an art gallery as a blind person will be just as fulfilling as for a fully sighted person https://www.rnib.org.uk/blind-artist-launches-genuinely-audio-visual-art-exhibit-aid-talking-books.

However, a couple of years ago, I excitedly stumbled across their temporary gallery, in use while the painstaking restoration process was being finished, but I was left to my own devices in an exhibition I found bewildering and incomprehensible. I had no idea what I should ask the assistants to help me understand, and instead was happily distracted by the incomparable view of the city which in itself gave me the sense of elevation I needed. I hope Collective put their money where their mouth is for their relaunch later on this year, because their relaunch is a very impressive and ambitious project. They hope to create a visitor experience that encompasses not just contemporary art but heritage and science, having restored Playfair’s original observatory from 1818. They’ve put a great deal of effort into letting visitors choose the level of freedom or support and guidance that they might need and are hoping to create a space where people feel especially welcome, relaxed and inspired to observe their own reactions and engage in dialogue with others.

And of course, this should perhaps be the main point of creating, funding, and visiting contemporary art in the first place. The thoughts, conversations and debates that follow from experiencing and being affected by the art; the blending of the unique personal resonances that each viewer has due to their mood, life history and hopes for the future. I’m always interested in the ways one might catch something of the possibly ephemeral responses, solidifying them for just long enough to transmit a spark to the next along the circuit of new ideas, filtering through and co-creating a change in the zeitgeist. Or this is perhaps too much like pinning down a butterfly, for no one can foresee where or what a thought or word might spark. The Sunday lunchtime poetry events that accompany the Royal Society of Artists annual exhibition have recently drawn me back again and again, to look at the artworks through someone else’s lens. The poems have been written in response to selected artworks, and the events allow time for questions and discussion about the themes that emerge. https://www.scotsman.com/lifestyle/culture/art/art-review-the-rsa-annual-exhibition-2018-royal-scottish-academy-edinburgh-1-4739530 Fortunate to attend the private viewing, I enjoyed reading Raman Mundair’s powerful poem accompanying a short film by Pernille Spence/Zoe Irvine. However, I felt rather rootless wandering around the vast exhibition alone. Returning to their poetry events and sitting next to the artworks has given me the time, space, comfort and company to enjoy the exhibition’s varied works in much greater depth.

Often people are simply afraid they will have nothing to say, or won’t have the required background knowledge to make comments that are informed enough without feeling embarrassed. Part of this perhaps stems from the fact that our hierarchical education system lays down very early whose ideas carry the most legitimacy and weight. What if we fully integrated both democratic dialogue and art into mainstream schools in the UK like Paolo Friere advocated, or alternative schools like Krishnamurti schools do? Rather than relegate it to a separate, second-class subject? If children’s ideas were treated with more respect from the beginning, and a constructive and ongoing dialogue was encouraged in the classroom, we might have a generation of learners who, as Sir Ken Robinson would say, are not afraid to make public ‘mistakes’.

In the meantime, the risk of appearing foolish or wasting precious time can be mitigated by friendly gallery staff, and creative ways to engage the viewer, without doing all of the ‘work’ for them. If, as a punter, you’re still a little unsure, here’s some handy tips to make the most of your experience. At least let people know they can have an exhibition list for basic information about what they are looking at. If people have some background knowledge of an artist and painting, or their sense of curiosity is piqued with the help of a friendly assistant, they might just spend longer than 30 seconds in front of it…come and see it again..read about it online..discuss it..respond to it artistically..maybe even buy it!

Lisa Williams