The Madness of Merlin

Those whom the gods destroy, they first make mad

Euripides

In recent years, in other places, I have demonstrated that King Arthur really did once exist, when from the obscure seed that was his life sprung up the legion of legends that constitute the Arthurian myth. If our great king existed, then, is it not also possible that the other members of his pantheon are also real? This leads us to Merlin, the spell-singing court sorcerer of Camelot, whose vitality supported by a wide array of sources. The Welsh chronicle known as the Annales Cambraie tells us.

573 AD: The battle of Arfderydd between the sons of Eliffert and Gwenddolau son of Ceidio; in which battle Gwenddolau fell; Merlin went mad.

A medieval Welsh triad sums up the battle perfectly;

The three frivolous causes of battle in the Isle of Britain.

…The second was the action of Arderydd, caused by a bird’s nest, in which 80,000 Cambrians were slain…

The battle of Arfderydd & Merlin are tied together in a number of old Welsh poems. They tell the story of a great civil war among the native Britons, climaxing at the battle of Arferydd. After the battle Merlin lost his mind then ran off to be a hermit in the Caledonian Wood. A sterling effort in finding the battle site was made by the great nineteenth century Scottish antiquarian, William Forbes Skene. His ‘Notice of the site of the Battle of Ardderyd or Arderyth‘ in the PSAS of 1864-65 shows this often brilliant scholar at his very best.

Where, then, was this battle fought? We ought, in the first place, to look for it in one of the great passes into the country; & a curious passage in Fordun gave me a clue to the probable situation. In his notice of Saint Kentigern, he describes, evidently from some older authority, his meeting in the desert a wild man, who informs him that his name was Merlin, & that he had lost his reason, & roamed in these solitudes because he had been the cause of the slaughter of so many men : ‘qui interfecti sunt in bello, cunctis in hac patria constitutis satis moto, quod erat in campo inter Lidel et Carwanalow situato. The last part of the Latin means, ‘fought on the plain between Liddel and Carwannok.’ Liddel, as is well known, is the name of the river which flows westward through Liddesdale, & joins the Esk about nine miles north of Carlisle. Near the junction is the border between England & Scotland, & from thence the flat & mossy district, called the Debateable Lands, bounded on the east by the Esk, extends to the Solway Firth

This nugget of information was the catalyst for Skene, who now begins to hone in on the battlefield, near Longtown in Cumbria, where a small settlement called Athuret immediately raised his heckles. Taking the train down from Edinburgh, Skene found a place to stay in Longtown, whose landlady was quite shocked to see anybody staying in the area at all. Skene continued;

About half a mile from Longtown is the church & rectory of Arthuret, situated on a raised platform on the west side of the River Esk, which flows past them on a lower level; & south of the church & parsonage there rise from this platform two small hills covered with woods, called the Arthuret Knowes. The top of the highest, which overhangs the river, is fortified by a small earthen rampart, enclosing a space nearly square, & measuring about 16 yards square. On returning to Longtown, I asked the old guard whether he knew of any place called Carwandlow. He said that Carwinelaw was the name of a stream which flowed into the Esk from the west about three miles north of Longtown, & also of a mill situated on it, & that beyond it was a place called the Roman Camp.

At this point Skene visited the ‘camp,’ which is today known as the Moat of Liddle. He thought it a magnificent native strength, & was taken aback by its splendid views, including the knowes at Athuret in the distance. He went on;

Between the fort & Carwhinelaw is a field extending to the ridge along Carwhinelaw, which is about half a mile off… The old farmer of the Upper Moat, who accompanied us, informed me that the tradition of the country was that a great battle was fought here between the Romans; & the Picts held the camp, in which the Romans were victorious; that the camp was defended by 300 men, who surrendered it, & were all put to the sword & buried in the orchard of the Upper Moat, at a place he showed me. This part of the tradition is curious, as the Triads mention the Gosgord of Drywon-ap-Nudd at Arderyth which consisted of 300 men.

The name of Erydon, which Merlin attaches to it as a name for the battle, probably remains in Ridding at the foot of the fort, & I have no doubt at all that the name Carwhinelaw is a corruption of Caerwenddolowe, the caer or city of Gwenddolowe, & thus the topography supports the tradition.

This is all breathless work, & leaves us moderns with a few scanty crumbs to discover. The only object of interest I could scrape up myself concerned another fortification, a mile or so to the North of the Moat of Liddel, where; ‘there is a slight eminence called Battle Knowe by Prioryhill farm near Canonbie. It feels like a burial mound & tradition says that a battle was fought here & human bones have frequently been dug up but no authentic information can be obtained to confirm the supposition. (Ordnance Survey Name Book 1858)

Having discovered battlefield where Merlin went mad, let us now practice the very modern art of Psychoanalysis on his mind. By studying the old poems & stories surrounding Merlin, it is clear he had paranoid schizophrenia, the modern terminology of a condition as old as humanity itself. Joan of Arc heard voices & in the first Book of Samuel, Saul shows all the classic symptoms of a lunatic. The following are extracts from a report by the World Health Organisation in 1992.

Paranoid schizophrenia is the most common type of schizophrenia in most parts of the world. The clinical picture is dominated by relatively stable, often paranoid, delusions, usually accompanied by hallucinations, particularly of the auditory variety, and perceptual disturbances. Examples of the most common paranoid symptoms are:

Delusions of persecution, reference, exalted birth, special mission, bodily change, or jealousy; Hallucinatory voices that threaten the patient or give commands, or auditory hallucinations without verbal form, such as whistling, humming, or laughing;

Hallucinations of smell or taste, or of sexual or other bodily sensations; visual hallucinations may occur but are rarely predominant. Thought disorder may be obvious in acute states, but if so it does not prevent the typical delusions or hallucinations from being described clearly. Affect is usually less blunted than in other varieties of schizophrenia, but a minor degree of incongruity is common, as are mood disturbances such as irritability, sudden anger, fearfulness, and suspicion.

Merlin appears the medieval tale Lailoken and Kentigern, which states: “…some say {Lailoken} was called Merlynum.” This name change leads us to the 9th Century Historia Brittonum of Nennius, which states that in the late 6th century, ‘Talhaiarn Tataguen was famed for poetry, and Neirin, and Taliesin and Bluchbard, and Cian, who is called Guenith Guaut, were all famous at the same time in British poetry.’ Nobody has ever established the further identity of Bluchbard, but the ‘Luch’ embedded in the name links it to the ‘Lok’ within Lailoken. Thus Lailoken the Bard easily becomes Luch the Bard, then Bluchbard. Perhaps, perhaps not, but there’s enough in there to believe it so.

Moving on from digressive conjecture, in the tale of Lailoken & Kentigern, Merlin is depicted as seeing visions & hearing voices, the classic symptoms of paranoid schizophrenia. On one occasion a voice from heaven says; ‘because you alone are responsible for the blood of all these dead men, you alone will bear the punishment for the misdeeds of all. For you will be given over to the angels of Satan & you will have communion with the creatures of the wood.‘ We probably all have experienced a moment in public when a person of obvious insanity wanders around screaming wildly & talking to themselves. Lailoken and Kentigern reports the same thing of Merlin, who used to interrupt the services of his clergy by shouting out prophecies. It also has Merlin seeing bright visions of ‘martial battalions’ lighting up the sky shaking their lances ‘most fiercely’ at him, & then dragged off into the woods by an evil spirit. In another text, the Itinerarium Kambriae of Giraldus Cambrensis, he is said to have lost his mind just before the battle of Arferydd when he saw a monster in the sky.

On Thursday 11th September 2008 The Independent ran a fascinating story about the son of Patrick Cockburn, a foreign correspondent. His name was Henry, who told the paper; ‘do I have schizophrenia? My mother and father and the dreaded psychiatrist definitely believe I am schizophrenic. They have grounds for their belief, such as my being found naked and talking to trees in woods. Yet I think I just see the world differently from other people.’ Patrick added, ‘Jan and I soon became familiar with the distorted landscape of the strange world in which Henry was now living. The visions and voices, though the most dramatic part, were infrequent. He spoke vaguely of religious and mystical forces and was extremely ascetic, adopting a vegan diet and not wearing shoes or underpants.’

Henry certainly sounds like a modern day Merlin. When the mind is being bombarded by extra-sensory stimuli, there is only one true way to ‘let of the steam,’ & that was summed up nicely by Henry; ‘my main strength was art, and it was through art that I understood my world.‘ Among the all the arts poetry is perhaps the oldest, yet its beauty is that anyone can write a poem. The writing of them is seen by modern psychology as a therapeutic tool to aid schizophrenia. In the Journal of Poetry Therapy (June 2010), Noel Shafi writes; ‘a patient exhibited negative symptoms including social withdrawal. Under clinical observation she successfully wrote renkus describing her everyday life & seasonal feelings. After 13 months of renku therapy the therapist observed improved social functioning &decreased negative symptoms in the patient.’

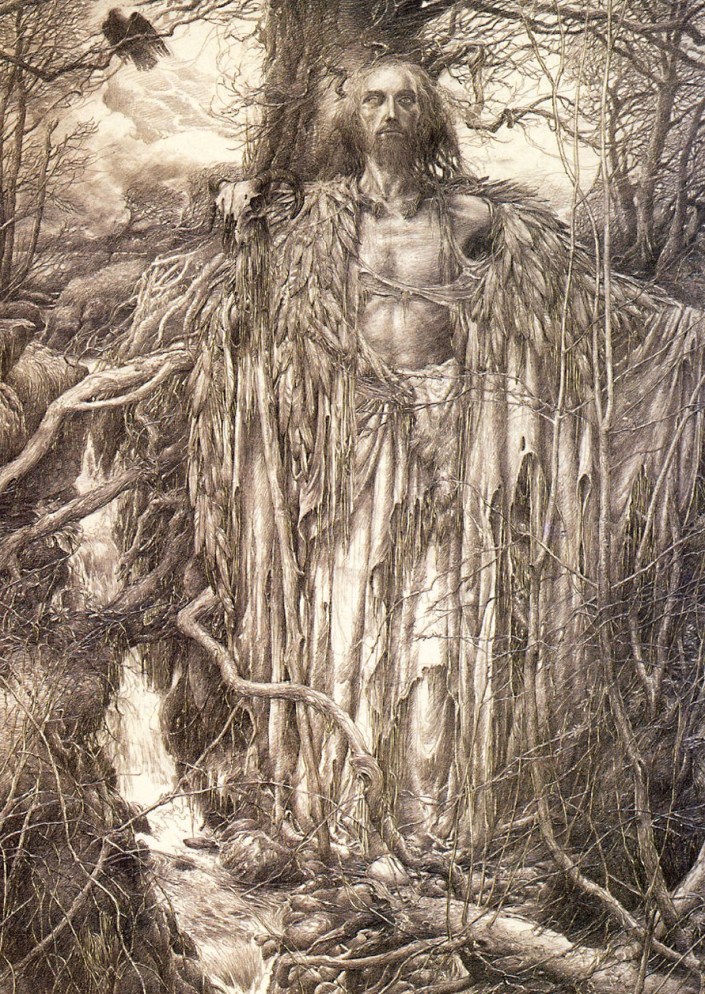

This brings us neatly to the ‘therapeutic’ poetry of Merlin himself. While he was in the woods, fuelled by the typical poetic salve that is insanity, Merlin composed a number beautiful poems, of which 6 still survive. In them solid traces of schizophrenia can be found. They also show the skill of an accomplished bard, the first step on the ladder to becoming a Druid. Inbetween is the Ovates, the title given to a bard after twelve years of intense poetic training. On attaining this second rank, the bard will develop visionary powers, being able to see into the future & commune with long dead ancestors. It must have been a total nightmare experience for Merlin once he lost control of his visionary mind. He was not the bearded wise-man of Arthurian mythology, but a man in need of series help.

Throughout his poetry we can detect the possible reason behind Merlin’s madness, the catalyst that sent him over the edge. It begins with the tradition of Gwendydd being his twin sister, which is given in the aptly titled, ‘The Dialogue Between Myrddin and His Sister Gwenddydd’ from the Red Book of Hergest.

Myrddin

Since the action at Arderydd and Erydon

Gwendydd, and all that happened to me,

Dull of understanding I am–

Where shall I go for delight?

Gwenddydd

I will speak to my twin brother Myrddin,

wiseman and diviner,

Since he is used to making disclosures

When a girl goes to him.

The tone of the first stanza is sullen & reflective. We can work out why from the following stanza from the Black Book of Carmarthen;

Sweet appletree that grows in the glade!

Their vehemence will conceal it from the lords of Rydderch,

Trodden it is around its base, and men are about it.

Terrible to them were heroic forms.

Gwendydd loves me not, greets me not;

I am hated by the firmest minister of Rydderch;

I have ruined his son and his daughter.

Death takes all away, why does he not visit me?

For after Gwenddoleu no princes honour me;

I am not soothed with diversion, I am not visited by the fair;

Yet in the battle of Ardderyd golden was my torques,

Though I am now despised by her who is of the colour of swans.

So here we have Merlin talking to the trees. It also introduces Rydderch Hael into the story, the King of Strathclyde who had married Merlin’s sister. With the line, ‘I have ruined his son and his daughter,’ we have a clue as to why Merlin went mad. If Rydderch is his brother-in-law, then the children in question were his nephew & niece. In the next line he says that ‘death takes all away,’ which hints that it was Merlin himself who killed them. No wonder his sister ‘loves him not!’ The emptiness of the last few lines portray his soul in dejected reclusion. His lord Gwenddoleu is dead & his mind is full memories of when he was wearing the ‘golden torques.’ The pathos of the piece gives us an excellent insight into Merlin’s mind at the time of his madness. He is obviously suicidal, a thread which the Dialogue poem expands on;

Myrddin

Great affliction has fallen upon me,

And I am sick of life–

I feel heavy affliction.

Dead is Morgenau, dead is Mordav,

Dead is Moryen, I wish to die!

Could Merlin, by surrounding himself with nature & solitude, be seeking reaffirmation with a forgiving god in the woods. Not wanting to disturb him too much, I think we should leave Merlin in the soft, safe confines of his Caledonian Woods. We find him talking to a little piglet & bidding him hide from the ‘dogs of Rhydderch,’– who were out to get them both – that classic delusion persecution, where conspiracies are found at every turn.

Listen, O little pig! happy little pig,

Do not go rooting on top of the mountain.

But stay here, secluded in the wood.

Hidden from the dogs of Rhydderch the Faithful.

I will prophecy–it will be truth!

There has always been a certain sense of the insane about the poet. John Clare spent years in an asylum churning out new cantos of Don Juan. TS Elliot composed his seminal Wasteland while undergoing psychological treatment at a clinic in Switzerland, while William Blake was blatantly as mad as a hatter. Of Baudelair, Jeremy Reed, in his Madness- the Price of Poetry (1989) wrote; ‘Baudelair was a prey to neurosis, his life is the record of an individual seeking to interpret incipient madness through the refinement of an aesthetic sensibility.’ So I guess Merlin & his madness are in pretty esteemed company, & I suppose you do have to be a bit mad to be a poet in the first place!

POEMS BY MERLIN

(& links)

The first three are found in the thirteenth-century Black Book of Carmarthen, with the others appearing in manuscripts from later centuries.

Yr afallennau – The Apple Trees

Yr Oianau – The Greetings

Ymddiddan Myrddin a Thaliesin – The Dialogue between Merlin & Taleisin

Cyfoesi myrddin a gwenddydd ei chwaer – The Dialogue between Merlin & his Sister

Gwasgargerdd fyrddin yn y bedd – The diffused song of Myrddin in his grave

Peirian Faban – Commanding Youth

The New Divan

I have just begun the transcreation of a book called A New Divan, recently released by Gingko. It had been inspired by the 200th anniversary of a collection of poems by Goethe, itself inspired by works of the medieval Pesian poet, Hafiz. I had no idea either existed, & thoroughly enjoyed my education into the texts at the recent Edinburgh International Book Festival, of which you can read more of here.

The main premise of A New Divan is to mirror Goethe’s subjects & themes using an international array of poets, whose creations would then be translated into English by another set of pets. Like a poetical UN. Intrigued, I requested a review copy from Gingko, which duly arrived yesterday. Running through the poems gave me the distinct impression that the collection was unfinished – that to match a production by Goethe, & the musical poetics of Hafiz, a single synthesizing mind had to work the ‘notes’ to order. With yesterday also being my last day reviewing at the Edinburgh Fringe, & with a full month’s worth of poesis stored in my creative antechambers, the catalyst had been sparked. I felt almost like Hammer did when hearing Hafiz in the original Persian for the first time, now compelled to translate it into German. I felt almost like Goethe did on hearing Hammer’s translation for the first time, now compelled to create a western reply to Hafiz.

Hafiz, Herr Goethe, wait for me!

Forming triplet fraternity,

By chance, or not by chance, I heard,

Entrancing dances of the word,

Rose Voice of East, rose Voice of West,

Where voices lay choice words to rest,

I’ll pluck them up, I’ll dust them down,

Then cap them with my laurel crown.

The vast majority of Goethe’s Divan is cast in octosyllabic metre, with simple but effective rhyme schemes. This of course I had to emulate, into which mould I would try & replicate the literary trickery of high-brow Persian poetics. Ultimately its the spirit of Goethe we are trying to please here, and I’m sure he’d be quite averse to Free Verse. Its still early days of course, but a project worth pursuing, the resulting piece, then, drawn from A New Divan, I shall name THE New Divan. Some of the fruits of my efforts thus fare are printed below.

Damian Beeson Bullen

CLARA JANES: The Song of the One Who Pours the Wine

As Shiraz roses sheer upclimb

These pages thro’, so hear the chime

Sung by the Holy Fool that stands

Beside the well at dusk – these hands

Reveal the decorated cup,

As if, from it, Jamshid did sup,

Containing worlds within wine-pools

Where ripple stars, submerging jewels,

Revealing patterns unimpair’d

By fauna & by flora shar’d,

A human heart or pulseless stone?

Upon a palm leaf focus hone

In some garden botanica,

Such as the one in Padua,

When famously illustrated

The metamorph you’ll see outspread!

As formula, in chimes, upswells

From caravans & tiny bells;

All things must change, all time must pass,

But even so, as higher class

Of thinker contemplates these things,

All fixed must be in place on strings –

Prayer beads of love & science.

Pour me another cup forth-hence,

Permitting detailed inspection

Of all that swims in reflection,

I’ll read the Cosmos as a sacred text,

Accepting what I’ll see I must acknowledge next.

Keeping electrons in a trance,

By atom procharge made to dance,

Like the limitless extension

Of the waves in curv’d connexion;

Deep secrets of this circuitrie

Reveals the links twyx atomie,

When object & subject between

Sees space collapsing mezzanine.

All this is held by such perfume

Exhaled by Shiraz rose in bloom,

Love is the scent-sway, & does etch

The first & best alphabet, which

Declaring in Persopolis,

This Human grace forever is!

Yet, falls the dusk, the Holy Fool

Sings by the well’s radiant pool,

The poet plucks from blazing flames

A flicker of all things, all names,

That brand my hands, together we

Repeat his arcane sorcery;

Nature, my one joy is to connect!

JAN WAGNER: Ephesus Ghazal

With tyrants who cavort like gods,

Our days cut-short at shortest odds,

Of these severe was one in faith,

His painters perpetrate a wraith,

With shaggy face & eyes like sleet,

Lads seven underneath his feet,

Prepar’d for freedom, so they hid

Themselves before Dawn lifts its lid.

Cavebound, the dog curl’d at their feet,

That loved them all with love complete,

While they first slept the Emperor

Gave rocks in cartloads the order,

‘Block up the entrance!’ Still they slept,

Dispersing trances, by them crept

Long centuries on centuries,

So deep that sleep it seems death is

Enmesh’d with slumbers – angel’s hand

As gentle as a grazing land,

Did turn them… dreadful, delicate;

Depending on which way the foot

Did point – to Heaven, down to Hell –

Limbs rolling as lads dreamlands dwell.

Eroded rocks, awoke hungry,

Thinking new morn was what they see

Just one night old; so sent to town

Their youngest, keenest, skills a crown,

Who found a bakers where once stood

The court, the baker’s face of blood

Drain’d white, straining for friends, in fear –

The proffer’d coin engrav’d, a clear

Depicted face, some king long dead,

“He was the emperor,” someone said,

A whole town came to gawp & glare

At this young marvel standing there,

Whose uncles & great-grandchildren

Were lang syne dust, distant aeon

In which he tried to grow a beard,

The townsfolk thought this very weird,

Tho’ simmering their pots were set,

They shrank Ephesus’ parapet,

To distant dots, even before

The millet cook’d; they wanted more

To see the cave, & when they did,

The other six no longer hid,

A clan of seven spread from death,

Who’d somehow shar’d eternal breath!

FADHIL AL-AZZAWI: Paradise on Earth

I see it as I leave the inn

The dark of night, an evil djinn

Pursues me close, each step I take,

These steps shall shudder as I shake

Dogs furious, a-bark behind

Like hunt-track wolves, outflung from mind,

I must drive this road’s solitude,

I must sing madly, loud & crude!

Dervish disguis’d as angel slips

Out from the mosque, threats on his lips,

Waving his stick thro’ air at me,

“Hey, you are losing your life!” he

Screams, “You have lost your life,” Adam,

Did you not know its forbidden

In this world to drink Eden’s wine?

But in Paradise, hey, that’s fine!

Go drink that wine, its bountiful

& free, search for the beautiful

Eyes, bountiful houris, gratis.

Oh master of my days, where is

This place, lord tell me where we are.

He points his stick up to a star,

“There,” utters he, “Eternity,”

Twinkling… blazing… “Up there!” says he,

Fluttering as the falcons rise

Evanishing in splendid skies!

I do not move, stricken with doubt,

I dare not move, Hafiz steps out

Arriving as he always does

As of-a-sudden surprises,

“My friend!” he laughs, “Why worry so?

Their walls are high & you have no

Wings there to fly – no – let us make

This mortal rock an angels’ lake ,

Look at these mountains rising up,

For when the flood oerflows the cup,

These seas, these oceans, all aswirl

With fish & gorgeous whales which whirl

About this Godufactured Earth,

Where even serpents maintain worth,

We must remember to release

Snakes from their cages, whom, in peace,

Shall twine around those fine branches

Of our tree – happy, glorious –

What more will we need than that?

REZA MOHAMMADI: Smoke

Unto the man I would return

Who once inside my shirt did burn.

At each lip’s precipice I fret

To find the voice I once did set

Down-dangling from a cigarette.

I ask the card-turn to unshroud

The revelations thro’ the crowd

That sweeps aside bird, plant & cloud.

Carry off, great Lord, this flower,

To tables fill’d by my mother,

& to the house of my father,

& to the fish of the rivers

Whom, three times a day, take lovers,

Suicide’s soft deliverers.

I’m six years old, care to buy bread?

What am I doing here, I said.

Carry my soul to the tented

Gypsy mystic, tinted, scented,

Take it to be finger-printed.

I’ll never leave this street, y’know,

That named a missile long ago.

You’ll see I only came to buy

Some rolls of bread – you’ll see that I

Have seen exactly six years by.

Before the next man join’d my thread

Morning stopp’d gorging on his head,

& like this poem’s folding, he

Was thrown, was caught, within old me.

Hey! This much wind my shirt won’t stand,

We should not let this much cloud land.

The blacken’d body’s shrapnel flew

Right back to eat, snack, feast on you.

Why should I be God’s kick’d up dust,

I flow like ink from His fingers.

The broken lighters of his feet

Flicker & flare in mine like heat.

His heart a wet, spent ciggarette,

His mother’s lashes crudely set

Inside his pocket, food for worms,

With sister’s hair that fistfull squirms,

& those barb’d eyelids of his wife.

I wish somebody in his life

Had told him moons dont burst in flame

When clad in clothes by top brands made.

The one runs from me as he ran

From his ma’s table & her pan,

Thus I would like to tell him this,

How poet’s metamorphosis

Grows on lips like little roses

Caus’d by earth – which decomposes!

Even the river dodges me,

Even the doves take flight to flee

& all the Judas trees within

Are made of debris from this bin;

How was your face made up, I said,

What shade the scarf swath’d round your head?

Black-sooted in black suit I stand,

A dandelion in one hand,

Addresses I can’t call to mind,

As on moth-wings descends dusts fine,

Dusts upon petals de-scend-ing –

Now I’m forgetting everything.

FATEMEH SHAMS: Electrocardigram

My back she aches again today,

Three months ago they mov’d my heart

& ledg’d my vital spine apart,

Then wedg’d it in the vertebrae,

Now each musk-fragrant breath depends

On one thin vein that empties blood,

From darkness to new heart’s blood wends

My idiotic bruise of vein.

My wanton whore of heart, the pain

My back endures nobody should.

My ECG supplies, these days,

My news, headlines from past suck’d out –

A woman used to laugh about

Her love for one man & his ways,

When lavish hearts love’s healths endow,

Form windows facing long exile,

These bunch’d red muscles bled servile,

I wish it were a mirror, now!

The medic team with smiles aflock

Chirps “We had to move it a bit,

& from today we must admit

By beating hearts please set your clock,”

Alarmic systems rotten grown,

My lover new has ask’d last night

“Are all our words & movements known?”

I thought he quizz’d me for to see

How paranoid & how crazy

I was, my shadows hid from sight,

For years my shadow’s eyes did hide

In dresses – cities far & wide,

The final shadow ran its part

& in his fist a bleeding heart –

The doctors are the shadow’s foes

& paranoia diagnose

Expertly well, & for exile

Prescibe a perfect potion’s phial,

Moving the heart to think & feel

In times when no heart’s scar could heal.

JAAN KAPLINSKI: The Great Axe

Knew everybody since childhood,

He’d dreamt he was a shaft of wood

By axehead topp’d, his foes to fight

To chop off heads & branches smite!

He grew & chopp’d & splinters flew,

Heads fell & everybody knew

He was the sharpest one of all,

Most pitiless of axeheads’ fall,

Him from the toughest shell was cast

The special spirit naught could rust,

Let no-one ken the truth display’d,

He was just normal, iron-made,

Of brittle rust was he afraid,

Standing alone before mirror

He would check, those new red stains were

Upon his blade? He tried to wash

Away the rust stains with blood fresh

From wounds, but not enough to hide,

Until his peace one day defied,

Smashing the mirror angrily,

He fell inside some phantasie

Beyond the Looking Glass’s ledge,

Near marshes large by forest edge,

& realised his place was there,

In that swamp’s pool, & full aware

He transformed could be back into

A fist of mud-brown bog ore goo!

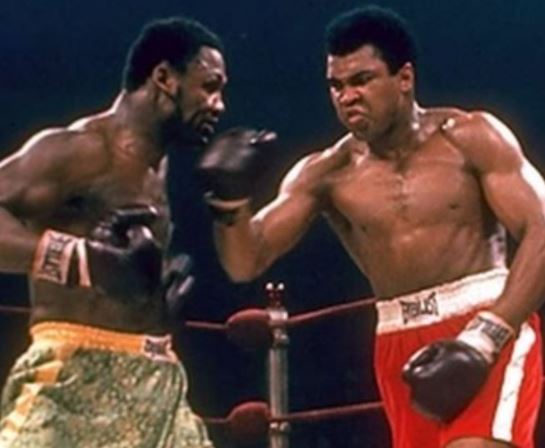

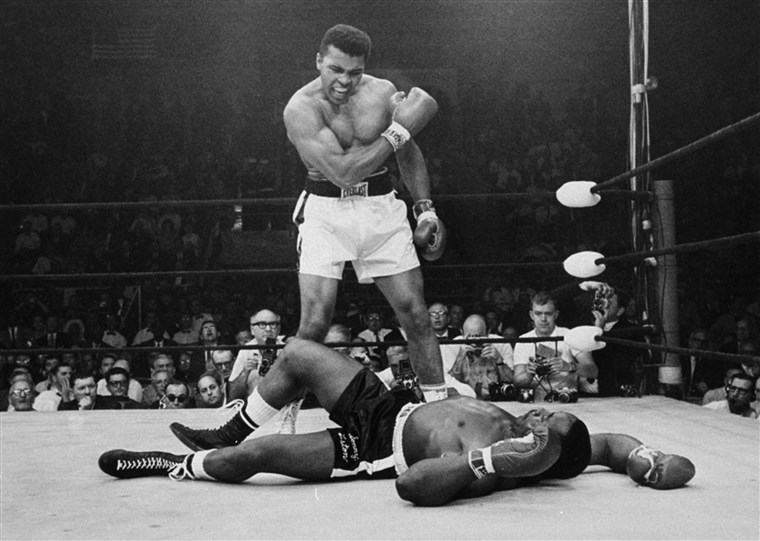

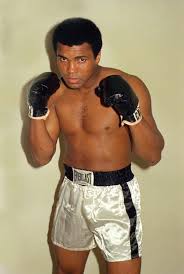

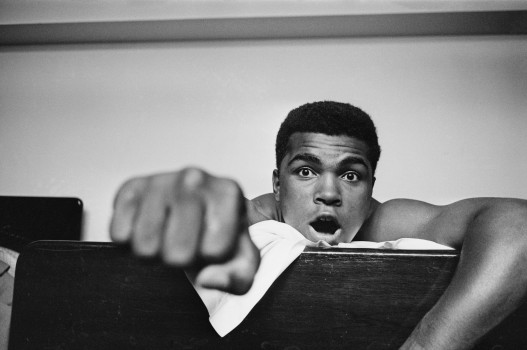

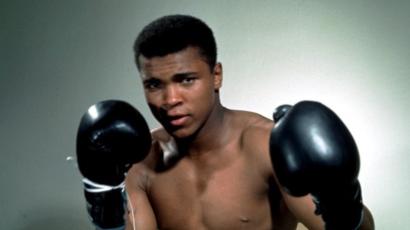

The Poetry of Muhammad Ali

The warrior poet is one of the more remarkable figures in history. In the English-speaking world, their zenith came with the horrors of World War One, when Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen & others veered away from patronising the soldier’s noble death with high-blown lyricism, & got down to expositing the true danger & desperation of combat. Fifty years later the world encountered a different kind of warrior poet, the boxer called Cassius Clay / Muhammad Ali who like a high-ranked bardic-trained Gaulish druid passed judgement on the age of Civil Rights.

I am America.

I am the part you won’t recognize.

But get used to me:

Black, confident, cocky.

My name, not yours.

My religion, not yours.

My goals, my own.

Get used to me.

Muhammad Ali

How Cassius Took Rome

To make America the greatest is my goal,

So I beat the Russians, and I beat the Pole,

and for the USA won the medal of gold.

Italians said: “You’re Greater than the Cassius of old´´.

We like your name, we like your game,

So make Rome your home if you will.

I said I appreciate your kind hospitality,

But the USA is my country still,

‘Cause they’re waiting to welcome me in Louisville.

LAST NIGHT I HAD A DREAM

LAST NIGHT I HAD A DREAM

Last night I had a dream, When I got to Africa,

I had one hell of a rumble.

I had to beat Tarzan’s behind first,

For claiming to be King of the Jungle.

For this fight, I’ve wrestled with alligators,

I’ve tussled with a whale.

I done handcuffed lightning

And throw thunder in jail.

You know I’m bad.

just last week, I murdered a rock,

Injured a stone, Hospitalized a brick.

I’m so mean, I make medicine sick.

I’m so fast, man,

I can run through a hurricane and don’t get wet.

When George Foreman meets me,

He’ll pay his debt.

I can drown the drink of water, and kill a dead tree.

Wait till you see Muhammad Ali.

Written by Muhammad Ali | Create an image from this poem

There live a great man named Joe

There live a great man named Joe

who was belittled by a loudmouth foe.

While his rival would taunt and tease

Joe silently bore the stings.

And then fought like gladiator in the ring.

CLAY COMES OUT TO MEET LISTON

Clay comes out to meet Liston

and Liston starts to retreat,

if Liston goes back an inch farther

he’ll end up in a ringside seat.

Clay swings with his left,

Clay swings with his right,

Look at young Cassius

carry the fight

Liston keeps backing, but there’s not enough room,

It’s a matter of time till Clay lowers the boom.

Now Clay lands with a right,

What a beautiful swing,

and the punch raises the Bear

clean out of the ring.

Liston is still rising and the ref wears a frown,

For he can’t start counting

till Sonny goes down.

Now Liston is disappearing from view,

The crowd is going frantic,

But radar stations have picked him up,

Somewhere over the Atlantic.

Who would have thought

when they came to the fight?

That they’d witness the launching

of a human satellite.

Yes the crowd did not dream,

when they put up the money,

That they would see

a total eclipse of the Sonny

VERSUS LISTON

I’m young,

I’m handsome,

I’m fast,

I can’t possibly be beat.

I’m ready to go to war right now.

If I see that bear on the street,

I’ll beat him before the fight.

I’ll beat him like I’m his daddy.

He’s too ugly to be the world champ.

The world’s champ should be pretty like me.

If you want to lose your money,

then bet on Sonny,

because I’ll never lose a fight.

It’s impossible.

I never lost a fight in my life.

I’m too fast;

I’m the king.

I was born a champ in the crib.

I’m going to put that ugly bear on the floor,

and after the fight I’m gonna build myself a pretty home and use him as a bearskin rug.

Liston even smells like a bear.

I’m gonna give him to the local zoo after I whup him.

People think I’m joking.

I’m not joking; I’m serious.

This will be the easiest fight of my life.

The bum is too slow; he can’t keep up with me;

I’m too fast. He’s old, I’m young.

He’s ugly, I’m pretty.

It’s just impossible for him to beat me.

He knows I’m great.

He went to school;

he’s no fool.

I predict that he will go in eight

to prove that I’m great;

and if he wants to go to heaven,

I’ll get him in seven.

He’ll be in a worser fix

if I cut it to six.

And if he keeps talking jive,

I’ll cut it to five.

And if he makes me sore,

he’ll go like Archie Moore,

in four.

And if that don’t do,

I’ll cut it to two.

And if he run,

he’ll go in one.

And if he don’t want to fight,

he should keep his ugly self home that night.

—Muhammad Ali

Ali ‘the poet’ must also go down on record as the author of the shortest poem in the language. According to Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, the shortest poem in the English language was Lines on the Antiquity of Microbes by Strickland Gillilan, which went, ‘Adam / Had’em.’ Ali beat this hands down with his sexy & supercilious, ‘Me / We.’ Yes, Muhammad Ali, you truly were the greatest.

READ

THE GODS OF THE RING

THE NEW DRAMATIC MUSICAL BY

DAMIAN BEESON BULLEN

The boy could fight too – sheer poetry in the ring, but he actually created a great deal of interesting, funny verse. Inspired by the barber-shop banter he heard in his youth, & driven through a supra-arrogant ‘I’m the greatest’ persona based upon a wrestler called Gorgeous George, the world became hooked on every word the young Cassius said – & he knew it, touching an entire planet thro’ his simple lyricism enabled by his global persona. “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.”

ALI V JOE FRAZIER

Ding! Ali comes out to meet Frazier

But Frazier starts to retreat

If Frazier goes back any further

He’ll wind up in a ringside seat

Ali swings to the left

Ali swings to the right

Look at the kid

Carry the fight

Frazier keeps backing

But there’s not enough room

It’s a matter of time

Then Ali lowers the boom

Now Ali lands to the right

What a beautiful swing!

And deposits Frazier

Clean out of the ring

Frazier’s still rising

But the referee wears a frown

For he can’t start counting

Till Frazier comes down

Now Frazier disappears from view

The crowd is getting frantic

But our radar stations have picked him up

He’s somewhere over the Atlantic

Who would have thought that

When they came to the fight

That they would have witnessed

The launching of a coloured satellite!

After becoming involved with the controversial ‘Nation of Islam’ group in the 60s, Clay changed his name to Muhammad Ali, which will stick unto eternity. His legacy is being forgotten by the millennial generation, unfortunately, as is his poetry. But there is a clear case that for while he was at the peak of his powers, more people heard, were touched by, & recited back his poetry than other individual on the planet before or since. Maybe not a better poet than Shakespeare, but definitely, during his hey-days, bigger!

ON THE ATTICA PRISON RIOTS OF 1971

He said breedom – Better Now

Better far— from all I see—

To die fighting to be free

What more fitting end could be?

Better surely than in some bed

Where in broken health I’m led

Lingering until I’m dead

Better than with prayers and pleas

Or in the clutch of some disease

Wasting slowly by degrees

Better than a heart attack

or some dose of drug I lack

Let me die by being Black

Better far that I should go

Standing here against the foe

Is the sweeter death to know

Better than the bloody stain

On some highway where I’m lain

Torn by flying glass and pane

Better calling death to come

Than to die another dumb

Muted victim in the slum

Better than of this prison rot

If there’s any choice I’ve got

Kill me here on the spot

Better far my fight to wage

Now while my blood boils with rage

Lest it cool with ancient age

Better vowing for us to die

Than to Uncle Tom and try

Making peace just to live a lie

Better now that I say my sooth

I’m gonna die demanding truth

While I’m still akin to youth

Better now than later on

Now that fear of death is gone

Never mind another dawn.

This poem was recited on air while in Ireland & depicts a hostage protest for better conditions which led to 29 prisoners being shot by soldiers. After reading the poem, Muhammad Ali related the struggle of the Afro-Americans for freedom and justice to the struggle of the Irish against British imperialism

THE LEGEND OF MUHAMMAD ALI

This is the legend of Muhammad Ali,

The greatest fighter that ever will be.

He talks a great deal and brags, indeed.

Of a powerful punch and blinding speed.

Ali fights great, he’s got speed and endurance.

If you sign to fight him, increase your insurance.

Ali’s got a left, Ali’s got a right;

If he hits you once, you’re asleep for the night

Written by Muhammad Ali | Create an image from this poem

To make America the greatest is my goal

To make America the greatest is my goal,

So I beat the Russians, and I beat the Pole,

and for the USA won the medal of gold.

Italians said: “You’re Greater than the Cassius of old´´.

We like your name, we like your game,

So make Rome your home if you will.

I said I appreciate your kind hospitality,

But the USA is my country still,

‘Cause they’re waiting to welcome me in Louisville.

LAST NIGHT I HAD A DREAM

Last night I had a dream, When I got to Africa,

I had one hell of a rumble.

I had to beat Tarzanís behind first,

For claiming to be King of the Jungle.

For this fight, Iíve wrestled with alligators,

Iíve tussled with a whale.

I done handcuffed lightning

And throw thunder in jail.

You know Iím bad.

just last week, I murdered a rock,

Injured a stone, Hospitalized a brick.

Iím so mean, I make medicine sick.

Iím so fast, man,

I can run through a hurricane and donít get wet.

When George Foreman meets me,

Heíll pay his debt.

I can drown the drink of water, and kill a dead tree.

Wait till you see Muhammad Ali.

Written by Muhammad Ali | Create an image from this poem

There live a great man named Joe

There live a great man named Joe

who was belittled by a loudmouth foe.

While his rival would taunt and tease

Joe silently bore the stings.

And then fought like gladiator in the ring.

Lines upon a Louisville Lip

Nine years ago, they said.

Before Liston the Bear Muhammad Ali would be dead.

But he went out. In just this way and with no fear,

Ali did the same trick to Foreman the Bull,

but this time in Zaire.

While you were waiting for George Foreman’s eye to mend

You said “Muhammad Ali’s reached his end.

He is too old, and has got slower,

And Foreman the Bull will bowl him over.”

When I said I was still the best

The suckers said: “He will never pass this test.”

But I pulled the wool over everybody’s eyes

And in round eight it was Foreman who was looking at the skies.

I float like a butterfly and sting like a bee,

But this time I showed my brain was the fastest part of me.

People said: “You can only win by slipping his fists,”

So I took them on and he could not resist,

For when the Bull began to slow

Muhammad Ali showed his punches,

by Allah, could land the blow.

Five million dollars is a lot to pay two men to fight,

And George’s showing is proof that this is robbery, not right.

Sure you need against him doublehitting power,

But Ali the Genius was the man of the hour.

Foreman’s a fighter of no great merit.

It is I who should receive the full five million credit.

Whipping George has made my day,

There is no nicer way I know of earning my pay.

But because this time I get one half the price I’m worth,

Next time Ali dances round the ring he’s asking twice the purse.

So next time ‘don’t match Bull and Master,

Because Muhammad Ali has shown he is much the faster.

I was perfect and Allah showed,

He’d realised, For as soon as I won

His lightning shot across the skies.

TRUTH

The face of Truth is open

The eyes of Truth are bright

The lips of Truth are ever closed

The head of Truth is upright

The breast of Truth stands forward

The gaze of Truth is straight

Truth has neither fear nor doubt

Truth has patience to wait

The words of Truth are touching

The voice of Truth is deep

The law of Truth is simple:

All you sow, you reap

The soul of Truth is flaming

The heart of Truth is warm

The mind of Truth is clear and firm

Through rain and storm

Facts are only its shadow

Truth stands above all sin

Great be the battle of life

Truth in the end shall win

The image of Truth is the cross

Wisdom’s message is his rod

The sign of Truth is the crescent

And the soul of Truth is God

Life of Truth is eternal

Immortal is its past

Power of Truth shall endure

Truth shall hold to the last

In the following interview, the controversial 1975 one with Playboy Magazine, Ali talks about his poetry & his newfound love of ‘sayings’

PLAYBOY:

Since a lot of people are wondering about this, level with us. Do you write all the poetry you pass off as your own?

ALI:

Sure I do. Hey, man, I’m so good I got offered a professorship at Oxford. I write late at night, after the phones stop ringin’ and it’s quiet and nobody’s around—all great writers do better at night. I take at least one nap during the day, and then I get up at two in the morning and do my thing. You know, I’m a worldly man who likes people and action and I always like cities, but now when I find myself in a city, I can’t wait to get back to my training camp. Neon signs, traffic, noise and people—all that can get you crazy. It’s funny, because I was supposed to be torturing myself by building a training camp out in the middle of no where in northern Pennsylvania, but this is good livin’—fresh air, well water, quiet and country views. I thought I wouldn’t like it at all but that at least I’d work a lot instead of being in the city, where maybe I wouldn’t train hard enough. Well, now I like it better than being in any city. This is a real good setting for writin’ poetry and I write all the time, even when I’m in training. In fact, I wrote one up here that’s better than any poem in the world.

PLAYBOY:

How do you know that?

ALI:

My poem explains truth, so what could be better? That’s the name of it, too,

Truth:

The face of Truth is open, the eyes

of Truth are bright

The lips of Truth are ever closed,

the head of Truth is upright

The breast of Truth stands forward,

the gaze of Truth is straight

Truth has neither fear nor doubt,

Truth has patience to wait.

The words of Truth are touching,

the voice of Truth is deep

The law of Truth is simple: All you

sow, you reap.

The soul of Truth is flaming, the

heart of Truth is warm

The mind of Truth is clear and

firm through rain and storm.

Facts are only its shadow, Truth

stands above all sin.

Great be the battle of life—Truth

in the end shall win.

The image of Truth is the Honorable

Elijah Muhammad, wisdom’s message is his rod

The sign of Truth is the crescent

and the soul of Truth is God.

Life of Truth is eternal

Immortal is its past

Power of Truth shall endure

Truth shall hold to the last.

It’s a masterpiece, if I say so myself.

But poems aren’t the only thing I’ve been writing. I’ve also been setting my mind to sayings. You want to hear some?

PLAYBOY:

Do we have a choice?

ALI:

You listen up and maybe I’ll make you as famous as I made Howard Cosell. “Wars on nations are fought to change maps, but wars on poverty are fought to map change.” Good, huh? “The man who views the world at 50 the same as he did at 20 has wasted 30 years of his life.” These are words of wisdom, so pay attention, Mr. Playboy. “The man who has no imagination stands on the earth he has no wings, he cannot fly.” Catch this: “When we are right, no one remembers, but when we are wrong, no one forgets. Watergate!” I really like the next one: “Where is man’s wealth? His wealth is in his knowledge. If his wealth was in the bank and not in his knowledge, then he don’t possess it—because it’s in the bank!” You got all that?

PLAYBOY:

Got it, Muhammad.

ALI:

Well, there’s more. “The warden of a prison is in a worse condition than the prisoner himself. While the body of the prisoner is in captivity, the mind of the warden is in prison!” Words of wisdom by Muhammad Ali. This is about beauty: “It is those who have touched the inner beauty that appreciate beauty in all its forms.” I’m even going to explain that to you. Some people will look at a sister and say, “She sure is ugly.” Another man will see the same sister and say, “That’s the most beautiful woman I ever did see.” How do you like this one: “Love is a net where hearts are caught like fish”?

PLAYBOY:

Isn’t that a little corny?

ALI:

I knew you wasn’t smart as soon as I laid eyes on you. But I know you’re gonna like this one, which is called Riding on My Horse of Hope: “Holding in my hands the reins of courage, dressed in the armor of patience, the helmet of endurance on my head, I started on my journey to the land of love.” Whew! Muhammad Ali sure goes deeper than boxing.

READ

THE GODS OF THE RING

The Requiem of Anna Akhmatova

Anna Akhmatova’s Requiem is a perfect piece

Of mid-20th Century epyllia

Anna Akhmatova is one of the greatest ever Russian poets, essayists & translators. During the climate of Stalinist oppression, between 1935 and 1940 she composed she composed the bulk of her long narrative poem, Rekviem. It was whispered line by line to her closest friends, who quickly committed to memory what they had heard. Akhmatova would then burn in an ashtray the scraps of paper on which she had written Rekviem. If found by the secret police, this narrative poem could have unleashed another wave of arrests for subversive activities. The poem would be published for the first time in Russia only during the years of perestroika, in the journal Oktiabr’ (October) in 1989. Mixing various genres and styles & forms, the poem’s scatteredness reflects the disintegration of self and the world that the old Russian order was experiencing- Anna had aristocratic blood.

Not under foreign skies

Nor under foreign wings protected –

I shared all this with my own people

There, where misfortune had abandoned us.

[1961]

INSTEAD OF A PREFACE

During the frightening years of the Yezhov terror, I

spent seventeen months waiting in prison queues in

Leningrad. One day, somehow, someone ‘picked me out’.

On that occasion there was a woman standing behind me,

her lips blue with cold, who, of course, had never in

her life heard my name. Jolted out of the torpor

characteristic of all of us, she said into my ear

(everyone whispered there) – ‘Could one ever describe

this?’ And I answered – ‘I can.’ It was then that

something like a smile slid across what had previously

been just a face.

[The 1st of April in the year 1957. Leningrad]

DEDICATION

Mountains fall before this grief,

A mighty river stops its flow,

But prison doors stay firmly bolted

Shutting off the convict burrows

And an anguish close to death.

Fresh winds softly blow for someone,

Gentle sunsets warm them through; we don’t know this,

We are everywhere the same, listening

To the scrape and turn of hateful keys

And the heavy tread of marching soldiers.

Waking early, as if for early mass,

Walking through the capital run wild, gone to seed,

We’d meet – the dead, lifeless; the sun,

Lower every day; the Neva, mistier:

But hope still sings forever in the distance.

The verdict. Immediately a flood of tears,

Followed by a total isolation,

As if a beating heart is painfully ripped out, or,

Thumped, she lies there brutally laid out,

But she still manages to walk, hesitantly, alone.

Where are you, my unwilling friends,

Captives of my two satanic years?

What miracle do you see in a Siberian blizzard?

What shimmering mirage around the circle of the moon?

I send each one of you my salutation, and farewell.

[March 1940]

INTRODUCTION

[PRELUDE]

It happened like this when only the dead

Were smiling, glad of their release,

That Leningrad hung around its prisons

Like a worthless emblem, flapping its piece.

Shrill and sharp, the steam-whistles sang

Short songs of farewell

To the ranks of convicted, demented by suffering,

As they, in regiments, walked along –

Stars of death stood over us

As innocent Russia squirmed

Under the blood-spattered boots and tyres

Of the black marias.

I

You were taken away at dawn. I followed you

As one does when a corpse is being removed.

Children were crying in the darkened house.

A candle flared, illuminating the Mother of God. . .

The cold of an icon was on your lips, a death-cold sweat

On your brow – I will never forget this; I will gather

To wail with the wives of the murdered streltsy

Inconsolably, beneath the Kremlin towers.

[1935. Autumn. Moscow]

II

Silent flows the river Don

A yellow moon looks quietly on

Swanking about, with cap askew

It sees through the window a shadow of you

Gravely ill, all alone

The moon sees a woman lying at home

Her son is in jail, her husband is dead

Say a prayer for her instead.

III

It isn’t me, someone else is suffering. I couldn’t.

Not like this. Everything that has happened,

Cover it with a black cloth,

Then let the torches be removed. . .

Night.

IV

Giggling, poking fun, everyone’s darling,

The carefree sinner of Tsarskoye Selo

If only you could have foreseen

What life would do with you –

That you would stand, parcel in hand,

Beneath the Crosses, three hundredth in line,

Burning the new year’s ice

With your hot tears.

Back and forth the prison poplar sways

With not a sound – how many innocent

Blameless lives are being taken away. . .

[1938]

V

For seventeen months I have been screaming,

Calling you home.

I’ve thrown myself at the feet of butchers

For you, my son and my horror.

Everything has become muddled forever –

I can no longer distinguish

Who is an animal, who a person, and how long

The wait can be for an execution.

There are now only dusty flowers,

The chinking of the thurible,

Tracks from somewhere into nowhere

And, staring me in the face

And threatening me with swift annihilation,

An enormous star.

[1939]

VI

Weeks fly lightly by. Even so,

I cannot understand what has arisen,

How, my son, into your prison

White nights stare so brilliantly.

Now once more they burn,

Eyes that focus like a hawk,

And, upon your cross, the talk

Is again of death.

[1939. Spring]

VII

THE VERDICT

The word landed with a stony thud

Onto my still-beating breast.

Nevermind, I was prepared,

I will manage with the rest.

I have a lot of work to do today;

I need to slaughter memory,

Turn my living soul to stone

Then teach myself to live again. . .

But how. The hot summer rustles

Like a carnival outside my window;

I have long had this premonition

Of a bright day and a deserted house.

[22 June 1939. Summer. Fontannyi Dom (4)]

VIII

TO DEATH

You will come anyway – so why not now?

I wait for you; things have become too hard.

I have turned out the lights and opened the door

For you, so simple and so wonderful.

Assume whatever shape you wish. Burst in

Like a shell of noxious gas. Creep up on me

Like a practised bandit with a heavy weapon.

Poison me, if you want, with a typhoid exhalation,

Or, with a simple tale prepared by you

(And known by all to the point of nausea), take me

Before the commander of the blue caps and let me glimpse

The house administrator’s terrified white face.

I don’t care anymore. The river Yenisey

Swirls on. The Pole star blazes.

The blue sparks of those much-loved eyes

Close over and cover the final horror.

[19 August 1939. Fontannyi Dom]

IX

Madness with its wings

Has covered half my soul

It feeds me fiery wine

And lures me into the abyss.

That’s when I understood

While listening to my alien delirium

That I must hand the victory

To it.

However much I nag

However much I beg

It will not let me take

One single thing away:

Not my son’s frightening eyes –

A suffering set in stone,

Or prison visiting hours

Or days that end in storms

Nor the sweet coolness of a hand

The anxious shade of lime trees

Nor the light distant sound

Of final comforting words.

[14 May 1940. Fontannyi Dom]

X

CRUCIFIXION

Weep not for me, mother.

I am alive in my grave.

1.

A choir of angels glorified the greatest hour,

The heavens melted into flames.

To his father he said, ‘Why hast thou forsaken me!’

But to his mother, ‘Weep not for me. . .’

[1940. Fontannyi Dom]

2.

Magdalena smote herself and wept,

The favourite disciple turned to stone,

But there, where the mother stood silent,

Not one person dared to look.

[1943. Tashkent]

EPILOGUE

1.

I have learned how faces fall,

How terror can escape from lowered eyes,

How suffering can etch cruel pages

Of cuneiform-like marks upon the cheeks.

I know how dark or ash-blond strands of hair

Can suddenly turn white. I’ve learned to recognise

The fading smiles upon submissive lips,

The trembling fear inside a hollow laugh.

That’s why I pray not for myself

But all of you who stood there with me

Through fiercest cold and scorching July heat

Under a towering, completely blind red wall.

2.

The hour has come to remember the dead.

I see you, I hear you, I feel you:

The one who resisted the long drag to the open window;

The one who could no longer feel the kick of familiar

soil beneath her feet;

The one who, with a sudden flick of her head, replied,

‘I arrive here as if I’ve come home!’

I’d like to name you all by name, but the list

Has been removed and there is nowhere else to look.

So,

I have woven you this wide shroud out of the humble words

I overheard you use. Everywhere, forever and always,

I will never forget one single thing. Even in new grief.

Even if they clamp shut my tormented mouth

Through which one hundred million people scream;

That’s how I wish them to remember me when I am dead

On the eve of my remembrance day.

If someone someday in this country

Decides to raise a memorial to me,

I give my consent to this festivity

But only on this condition – do not build it

By the sea where I was born,

I have severed my last ties with the sea;

Nor in the Tsar’s Park by the hallowed stump

Where an inconsolable shadow looks for me;

Build it here where I stood for three hundred hours

And no-one slid open the bolt.

Listen, even in blissful death I fear

That I will forget the Black Marias,

Forget how hatefully the door slammed and an old woman

Howled like a wounded beast.

Let the thawing ice flow like tears

From my immovable bronze eyelids

And let the prison dove coo in the distance

While ships sail quietly along the river.

[March 1940. Fontannyi Dom]

If you enjoyed this article

Please make a donation

***

Birth of a Poet 8: Rome, then Home

Concluding the 1998 European adventure

Which made Damian Beeson Bullen a poet

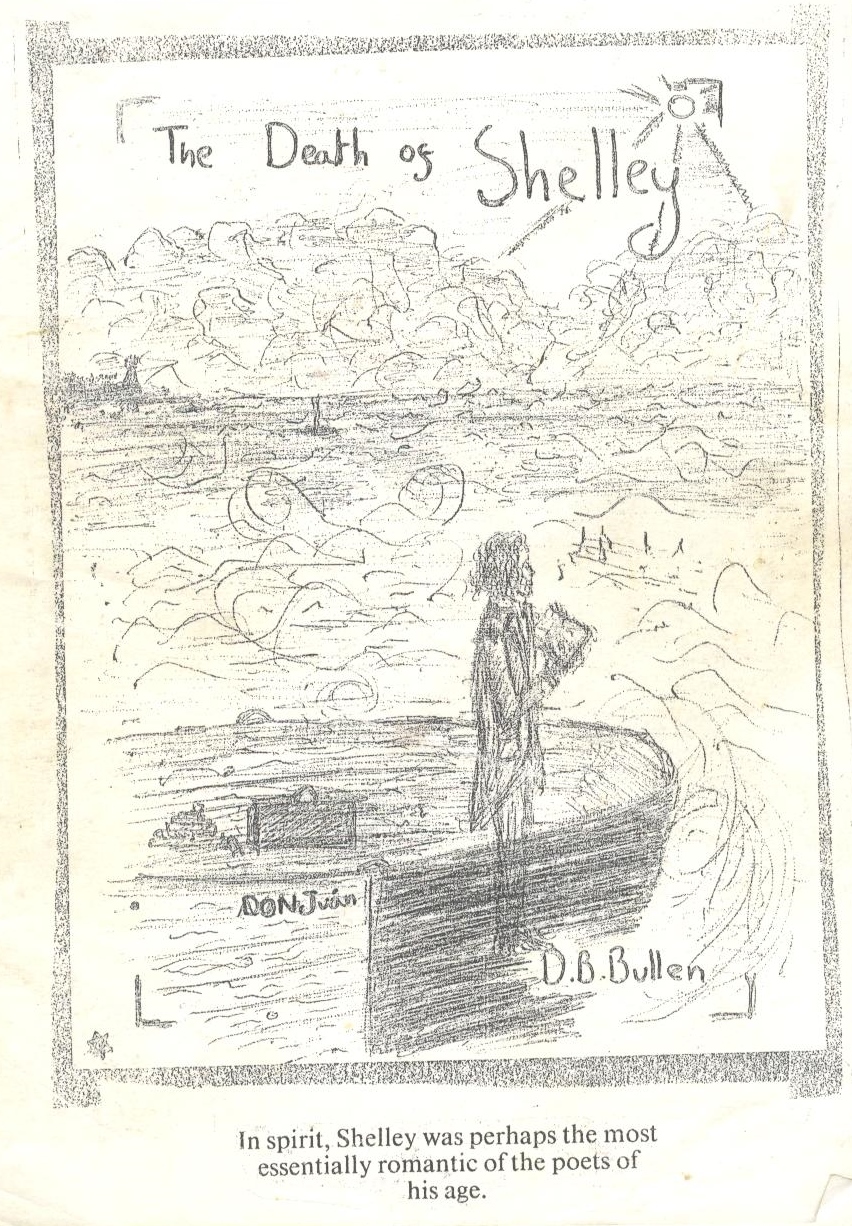

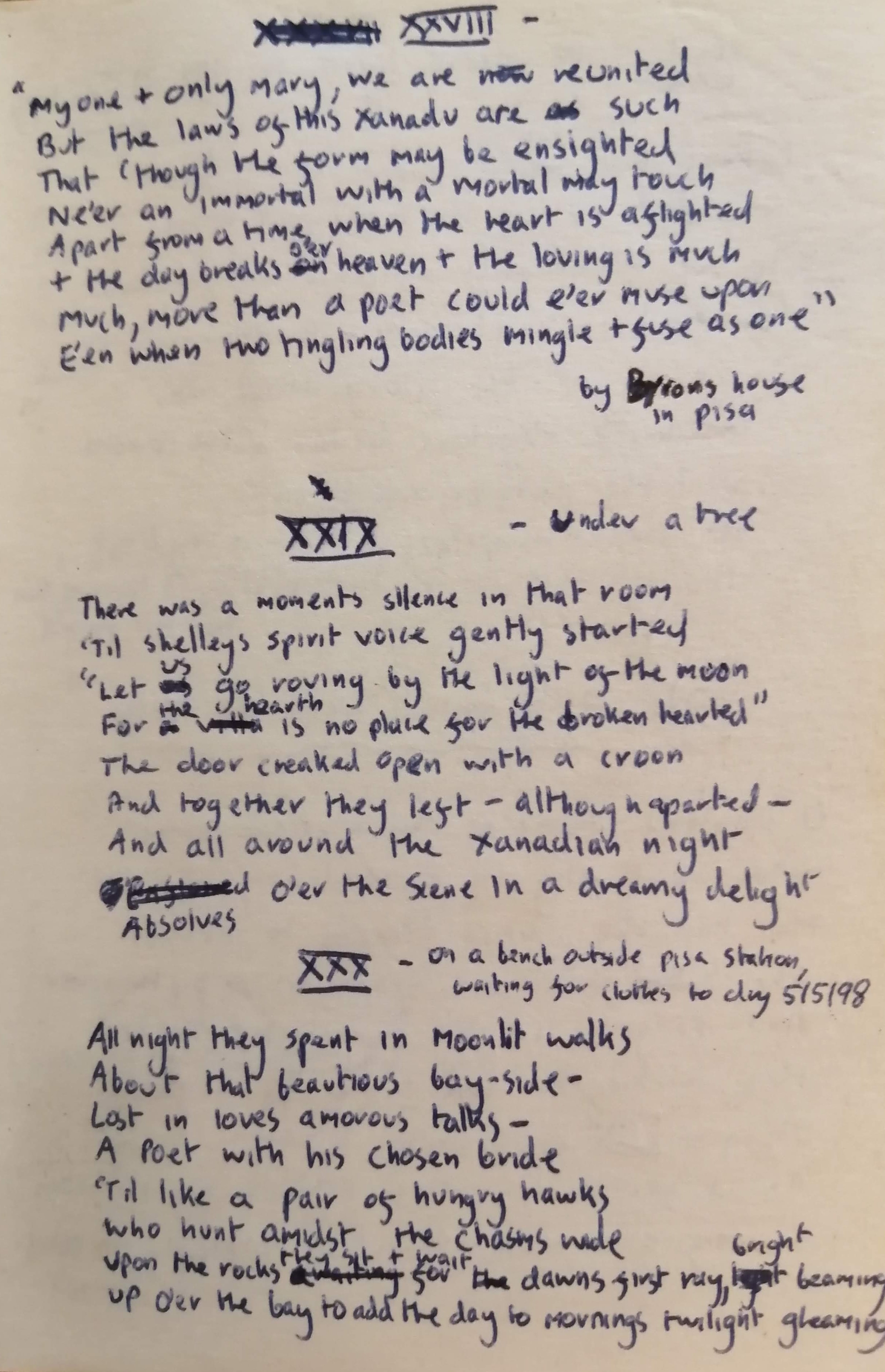

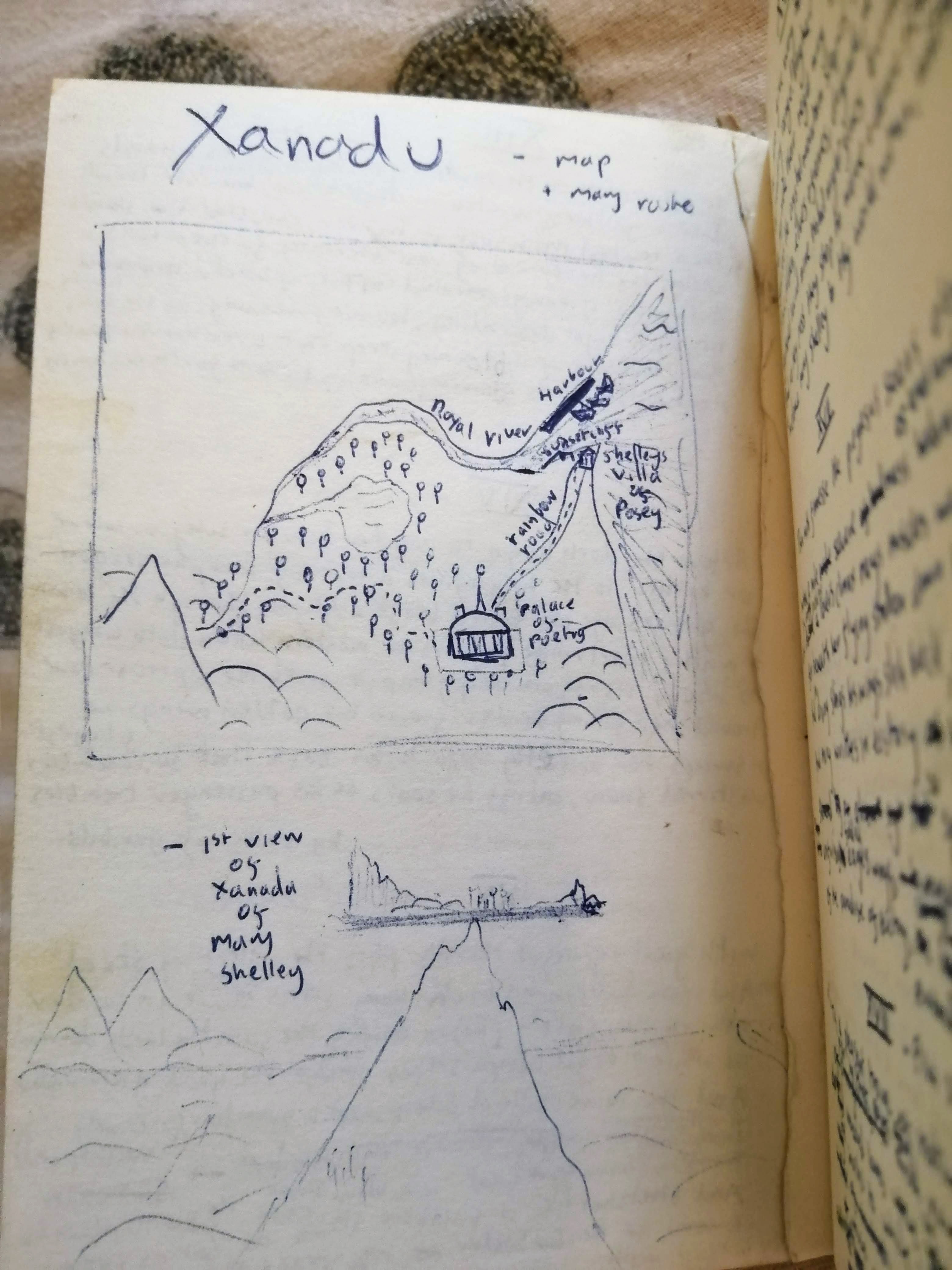

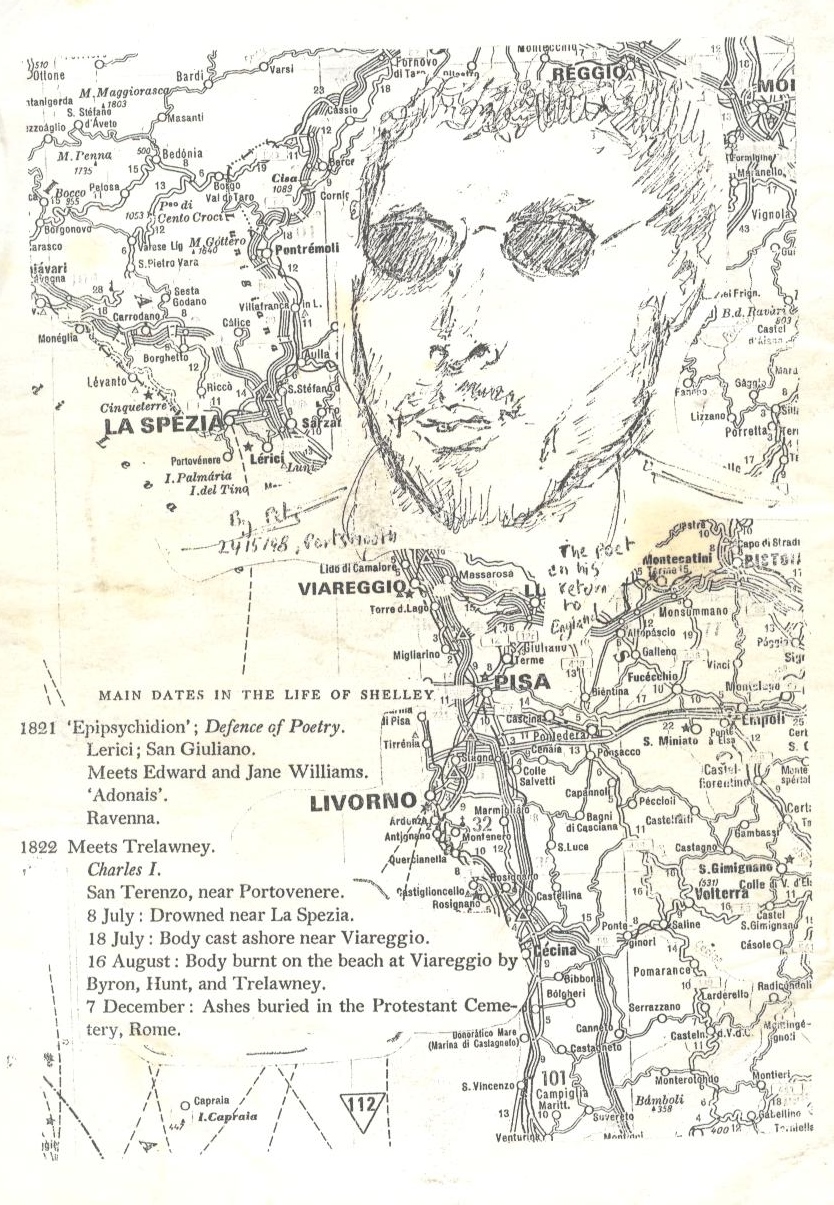

I am writing this in 2019, from my memory rather than typing up journals ad verbum. I will perform some of the telling with those stanzas of Ottova Rima I composed in Portsmouth, through the summer of 1999, as in them are my brightest recollections. As a general outline to my next few weeks on the road, from Le Spezia I first called in at Viareggio, a few miles down the coast, to the very spot where Shelley’s corpse was washed up & burnt, the painting of which began the whole ‘The Death of Shelley’ quest in the first place. I slept in my sleeping bag & built a little fire if I recall.

These were the very waters in which Shelley had drowned. He had been caught by one of the freak, sudden, snap-storms which lash this portion of the golden Tuscan coast. One of their number had consumed Shelley & his two companions, leaving forever a poet’s watery shrine. Shelley, in fact, had never learnt to swim. He was also an extemely proud individual & his turning away of help from the Italian fishermen while in the middle of the storm sealed the fate of himself, Edward Williams’ & the young Italian lad they had taken with them. These two factors had combined once before, upon Lake Geneva in 1816. Then, it was Shelley & Byron who were out sailing & caught by a sudden squall. Ther boat began to sink & Byron, being a swimmer strong enough to swim the Hellspont between Europa & Asia, offered to rescue his friend. But Shelley was adamant he would not be rescued & determined himself on going down with the boat. It took Byron’s invocation of Mary Shelley’s name to compel Shelley to consent to his rescue, but once on dry land he would never really get over this abashment of his pride.

(from) THE DEATH OF SHELLEY (1998)- Canto 3

Twas Leigh Hunt who came on O so fast,

Bringing bad news to below Byron’s window,

“By George, George, we have found him at last,

Wash’d up on the sands of Viareggio,

The anxious waitings of these ten days pass’d,

Bares sad fruit as his fate we now now!”

“Very well,” said his lordship, “We sleep here tonight,

Then tomorrow we rise & ride with first light.”Onwards, onwards, onwards rides the plot,

Soon all of the players shall be in their place;

Past the hovels of Viareggio two horses trot

As tho’ drawing a hearse at a funeral pace,

They reach the long beach, ever humid & hot,

Today the sands lie like a dead, desert waste,

Then stride to the side of the shimmering sea –

Awaiting with handshakes is grim-faced Trelawney!In the minute of which a lonely lifetime lasts

The swollen sands are stack’d into a heap,

Hunt stands agape, Byron stands aghast

As Shelley is unslumber’d from his sunken sleep

In horrid exhumation! his life’s light has pass’d,

Leaves a crack’d & blacken’d corpse where rotting flesh-things creep,

“Is – is – that a body?” Byron whispers, bleeding white,

“Aye!” sighs Trelawney, “Tis not a pretty sight!”With quickening quiet comes the onrushing roar

Of the hush’d seawashes in violences,

Shelley’s featherlite frame two young brutes bore,

Carried to the pyre amidst silences,

& crown’d! Hunt begins to over him pour

Frankincense & other oily essences –

A poet soon burning upon the gutted gyre,

His soul to the stars, his body to the fire.

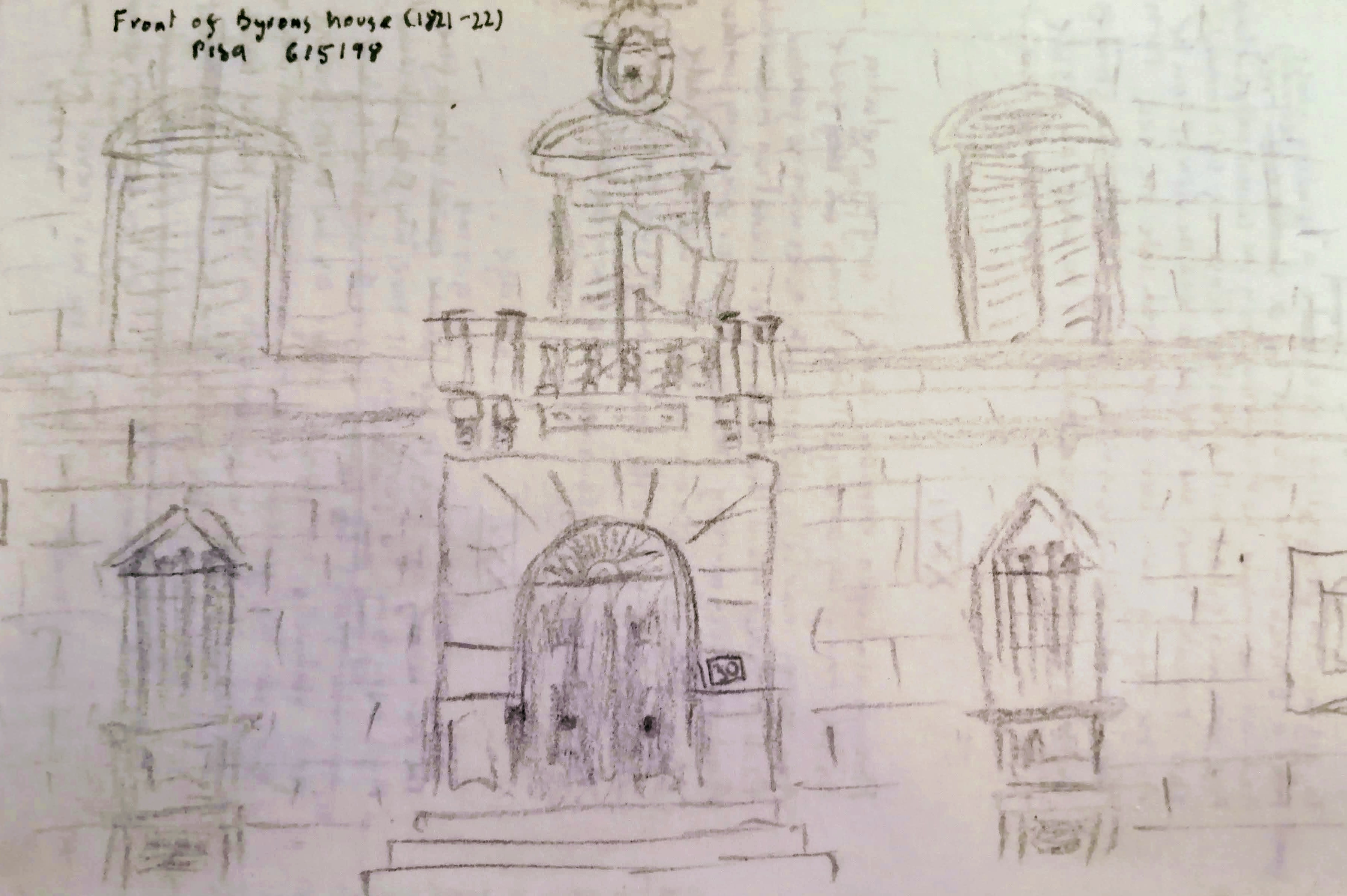

From Viareggio I spent a few more days in Pisa with the boys & my music, while hurtling thro’ canto 2 of my poem, which took only a week. Pisa is a perfect size, with everywhere walkable in about half an hour or so. The legacy of its empire is notable in its many noble buildings & beautiful churches. It is no wonder, then, that Byron & Shelley chose it as their place of residence. During my own stay I would often sit outside Byron’s old house & watch the sun set into the Arno, with its delicious blend of colours. Then, as I concluded the canto by Byron’s house, I was ready to go to Rome.

Heading down south on the click-clack train track

Its two AM, the conductor finds me

With a bag of books, the rags on my back

And in my hands a copy of Shelley.

I expect a Hampshire inspector’s flak

But he hands me his poetic pity –

Six hours later, the twilight before dawn,

I walk the streets of Rome awaitin’ morn.

I had chatted to Megadeth previously, who gave me two addresses – one for free nun’s food & another for the Forte Prenestina – a place where I could & has always been an oasis for me at the heart of the city ever since. I was only there last October reviewing a play, for example. I also went to see a play not far from the fort which starred a beautiful young actress I’d met on the lawn by the tower of Pisa. A delightful experience which found a way into my poem & my heart. On what was to be my last full day there I met a gorgeous young actress named Manuela, & we spent the day in perfect harmony. She was travelling with a show & had performed in Pisa the previous night. On discovering we were both bound for the capital the next day, it was agreed that I would come along to see the play. Here is a stanza I wrote to remember the occasion.

She is to me as the first star of eve

With ocean eyes & smile of teeth pearl white,

And breasts & bum like you wouldn’t believe,

My heart melteth at the sensual sight

Of beauties first essence, which I receive

In raptures, as we, by the Arno’s flight

Are as one with the sweet serene sundown –

“Meet me in Rome,” we kiss & she leaves town.

As I completed ‘The Death of Shelley’ in the Protestant Cemetary in Rome, on my beloved grandmother’s birthday (16th May), after two months of travel I was seriously ready to get home. I was penniless at the time, except for the emergency ten pound note which I had held in reserve, plus a tin of Hungarian beef I had been carrying with me since Budapest. After cashing in my money I immediately bought an ice-cream, reducing my funds by a further pound. Obviously this was not enough to get me home, but I had dodged the fares on trains from Belgium to Budapest & all the way to Rome, so felt confident of hitting the Channel coast at least.

I cash’d in my emergency tenner,

& with canned beef I bought in Hungary,

To busk up a little extra lira,

I hunger’d up the length of Italy

Whereon my last evensongs of Pisa,

Already it all seem’d a memory,

For Kapitano had moved on to France

To work the World Cup with a beggar’s dance.

I managed to jump trains all the way to Turin, stopping off in Pisa for one last romantic night of busking. From Turin my plan was to catch a train to the French border & from there make my way to Calais. However, things did not go to plan, for as my next train pulled into its destination, I was surprised to see, not a small border station, but tall statues, gorgeous pillars & a vast marble floor. Then in huge letters above me I read the words MILANO. I was now over two hundred miles off course in completely the wrong direction. Cursing my stupidity & sheer bad luck I got out my map & worked on another plan. The quickest way home was north through Switzerland & Germany, so I caught the last train that night toward the Swiss border.

So leaving gentle Arno to her flow,

Jumping trains to an uncertain future,

I once again view’d Viareggio,

Le Spezia, then pass’d thro Genoa,

Spent sunset in the streets of Torino,

Then caught a sleeper to the French border –

But travel does not always go to plan,

Somehow my train had landed to Milan!

The atmosphere on that journey was surreal, tracing the outline of the Italian alps as they sat black against the moonless gloom. It was sometime after midnight when I pulled up to Switzerland, & cheerily made my way to passport control. Unfortunately, when asked how much money I had I could only offer a few lira & a tin of Hungarian beef, & was promptly refused entry. The policeman planted a no entry stamp on the back of the page which sported my signature & address in Britain. Then he walked me to the border & tossed me into Italy, past a number of curious Italian police.

I was now sev’ral hundred miles of course,

& how it happen’d did not understand,

But youth is driven by a hidden force,

& made me jump a train to Switzerland

At whose harsh border found a smart resource

For they had rejected me out of hand –

I look’d like a tramp – past midnight grew tense,

Until I found a hole shewn from the fence.

Being twenty-one at the time, & in no position to be stuck at the border, I proceeded to tear out the page with the no entry stamp, find a hole in the fence & sneak into Switzerland. I made my way thro the empty streets like someone who had just escaped from Colditz, returning once again to the train station. There, while looking on the times of trains, I suddenly heard a “HALT!” & turned to see the same Swiss policeman who had thrown me out fumbling at his holster for his gun, which was soon trained on me. It is a strange sensation to have a gun aimed at you & so I thrust my hands in the air & awaited my fate. This was an ignominous kick up the ass, literally, back into Italy past the laughing Italian gaurds.

This was the final straw for me, & so once again returning through the hole in the fence I travelled into Switzerland for another five miles to the next station & waited for a train. The sun was just beginning to rise at this point, with dawn ever brightening the scene. Unluckily for me this made me visible & I began to worry as a police car suddenly began to drive toward the station, park up & eject two burly looking men.

“Your passport please?” they asked on discovering my nationality. I could tell they knew something was wrong, but looking through the passport could find nothing. It was very difficult to hold back the cheer as they gave me back my passport & drove away. However, that cheer did come when the 5 am train arrived & whisked me North.

Things would soon take another curious turn. I made Zurich safely enough, & pottered around on the trams for an hour or two, before catching a train to the capital, Bern. However, the mornings exertions had worn me down & I soon fell asleep, instead of jumping the train. Imagine my surprise, then, to be woken up at Bern by the conductor & two policemen, who frogmarched me off the train into a room at the station. From there I was taken to a holding cell, shared by four West Africans & a Kosovan, all in the country illegally. All there was top do there is eat the megre meals, take an hours exercise a day & watch endless reels of MTV. Fortunately for me I had a passport & it was soon decided that I would be deported.

I shyall always carry one incident with me. Not long after being locked up I desired the return of my notebooks & pen. After pouring my soul into the composition of the Death of Shelley, I wanted the manuscript close to me. The thought of it being lost by the Swiss autharities rankled me, & besides, there were a few corrections that needed making. So I began to press the contact button in order to get its return, but my request was refused. This wound me up, so I proceeded to tap out a percussive rythym on the buzzer, which I knew would infuriate the gaurds. A few moments later I had been taken to a solitary cell of confinement – & still no notebook! So I proceeded to go through the first album by the stone roses at the top of my voice, acapella style with bongo accompaniament, & got as far as She Bangs the Drums before five massively-forearmed gaurds burst in with a flurry of punches, calming me down somewhat.This I completely ignored & insisted on the return of my notebook. Finally my protestations were heard & I was given the poem & immediately fell as quiet as a mouse.

They marched me on a fancy Swiss Air Jet,

Handcuffed until the very last moment,

For I had slipped right thro their border net,

Back to mine own contree had to be sent,

On fine french wine my flight home growing wet

& thanks to their filthy rich government –

I had thirty-five pounds worth of Swiss Francs,

To sexy stewardesses kiss’d my thanks.

Two mornings later I was taken from the station, placed in a cell upon a train & transported to Zurich, where I was given twenty-five pounds in Swiss Franxcs & a seat on a swiss air jet bound for London. The cuffs were finally taken off me at the entrance to the plane, from where I found a nice window seat & helped myself to the free wine the attractive stewardesses insisted on giving me. Two hours later I had landed home in Heathrow, a little worse for wear from the wine but immensely relieved to be home. Whether it was enormous luck or not, ever since that moment I have been convinced that, if the poet will devote himself to the art, then the muses will always look after their own.

That evening I turned up at my pal’s house in Hackney and finally opened my tin of Hungarian beef. I can’t recall it’s taste too well, I think it was good enough. Maybe I should have waited to sober up off the Swiss wine to fully appreciate it!

PASSPORT POST-SCRIPT

I travelled widely following those amazing few days that whisked me from Rome to London, & had only ever had one bit of trouble with what is, in essence, an invalid passport. In 2004 I sailed through the enigmatic archipelago to the East of Stockholm & across the Baltic sea to Tallin, the charming capital of Estonia. I was making my way to the city to visit some friends of mine, & was very much looking forward to arriving. Unfortunately, at passport control I was very laisez faire about the matter & chose the rather podgy, matron like battleaxe of a woman to show my documents to, resulting in the denial of entry. I quick call to the British embassy resulted in them agreeing to get me a new one – but this would have reduced my vodka drinking funds & also given the nasty Swiss border gaurd an eventual karmic victory. With my friends waiting for me it was quickly agreed that I would go with them to the embassy & leave my bags at the port, collecting them later on when I had a new passport. Once inside the country, & suitably fortified on strong Finnish vodka, I decided to try my luck back at the port – especially as I remembered the five ecstasy tablets that I had left in my luggage!

On return to the harbour, past the leviathian soviet architecture & enigmatic Estonia city walls, I was delighted to find different members of staff in the room where my bags were. I quickly smiled, picked them up & hurriedly made my way tout of the complex, only to bump into the very woman who had denied me entry in the first place.

“So you have got a new passport,” she said.

“Ehh! yes,” I quickly answered.

“Then welcome to Estonia!” she said & I was off in a taxi in a flash.

THE BIRTH OF A POET

************************

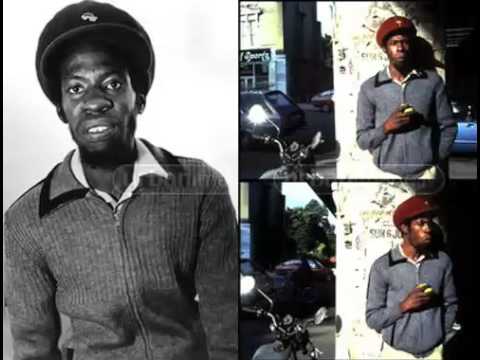

Remembering Mikey Smith

Linton Kwesi Johnson, Roger Robinson & Anthony Wall

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Sun 18 Aug, The New York Times Main Theater

With typical insouciance the dapper master of reggae poetry graciously bats aside the initial question of compere, Jamacain-raised author Leone Ross. He takes to the mic, regaling the Book Festival’s reverential, po-faced audience with the best known work of his friend and fellow genre-founding father, Mikey Smith.

Mi Cyann Believe it

Mikey Smith – social worker, writer, died in murky circumstances at a political rally in ’83 – composed a strident paean to the Jamaican diaspora, specifically those who landed on these shores. Smith’s first visit to Britain was documented in the 1982 film Upon Westminster Bridge by BAFTA-winning film maker Antony Wall – who was also on the Book Fest’s three-strong panel. The other being all round chief Rocker Roger Robinson.

Robinson, a protean talent, is affectionately teased for his whippersnapper status in the eyes of the godfather of Jamaican patois, who later delivers a blistering ‘half-poem, half-rant’ referencing Grenfel Tower and Windrush issues that LKJ avers ‘show us how far we have to go ‘ Happily it seems the legacy of LKJ and Mikey Smith is in safe hands.

Anthony Wall contributed a port-stained whine about the plethora oflLiterary festivals, the horrors of free wine, and the insight that Mikey Smith was not only the most important poet of the 20th Century, but almost as good as some English poets; whilst reducing the immeasurable contribution of the man recoiling beside him to absurdity by describing it as a ‘A fuck you to the man as we would call him.’ I kid you not!

After 15 minutes of inchoate waffling, the following Q&A consisted of the usual ‘I love you, you’re great, you saved my life sycophancy,’ along with the inevitable posh nob bleating a surreally unconnected anecdote about a pony before, RR ripped it up and finally LKJ himself had the audiences’ eyes brimming with his peroration to his dead father .

A true master

Irish Adam

Lin Anderson and Jacob Ross: Forensic Cops Delve into Horror

Edinburgh International Book Festival

20th August 2019

Lin Anderson, well known in Scotland as a Tartan Noir crime novelist and screen writer, has just published Sins of the Dead, her fourteenth book in the Rhona McLeod series. She is also the cofounder of Scotland’s annual festival of crime writing, ‘Bloody Scotland’. Anderson was born in Greenock, but with her latest novel located on the Isle of Skye in the west of Scotland, it was an inspired move to pair her for a discussion with fellow crime writer Jacob Ross. Currently living in Leeds, but born in Grenada, Ross has just finished ‘Black Rain Falling’, a crime novel set in the ‘fictional’ Caribbean island of Camaho. Following on from The Bone Readers, Black Rain Falling is the second book in his four-book series, the Camaho Quartet. The name is a nod to ‘Camerhogne’, the original Kalinago people’s name for Grenada. Ross has been a master of the short story form for several decades now, and is a polymath of the literary world; working also as an editor, creative writing tutor and judge. Al Hunter confidently chaired a lively and playful discussion that successfully drew out the author’s motivations and struggles in the process of writing crime fiction.

There are strong similarities between the protagonists of each book, though carrying out their work on either side of the Atlantic. Rhona MacLeod and Michael ‘Digger’ Digson are both forensic scientists, who have sidekicks with their own strong and memorable characters. There are also similarities in both authors’ approach to language and their defence of their use of local dialect in their writing. Ross has been speaking of this for many years, suggesting that the reader should not be patronised in order to enjoy a book. Anderson spoke of her jealousy at the musicality and rhythm of Caribbean cadence and yet both shared their fights with agents and publishers to keep important words and phrases that, if replaced with standard English, would lose the nuance, the emotion and the exactness of the cultural reference. Ross appealed to the sophistication of British readers who delight in the beauty of a different turn of phrase and will willingly work a little to understand unfamiliar words. Anderson shared her insistence that the evocative Scots word ‘boaked’ could and would not be replaced with the English word ‘gagged’. The conversation turned to the liberal amount of swearing in both books, and knowing both Grenada and Glasgow pretty well, I know it would be hard to ‘keep it real’ without some effing and blinding. Chair Al Senter wondered whether our more liberal times allowed for this, and the audience chuckled at Ross’ 85 year old mother’s disapproval, exclaiming that “I did not bring you up like that!”, but Ross pointed out the irony in taking offence at taboo language while simultaneously enjoying gory details of grisly violence. Often writers mention the strange freedom that comes with the death of their parents, and for Anderson the embarrassment had come from writing about sex.