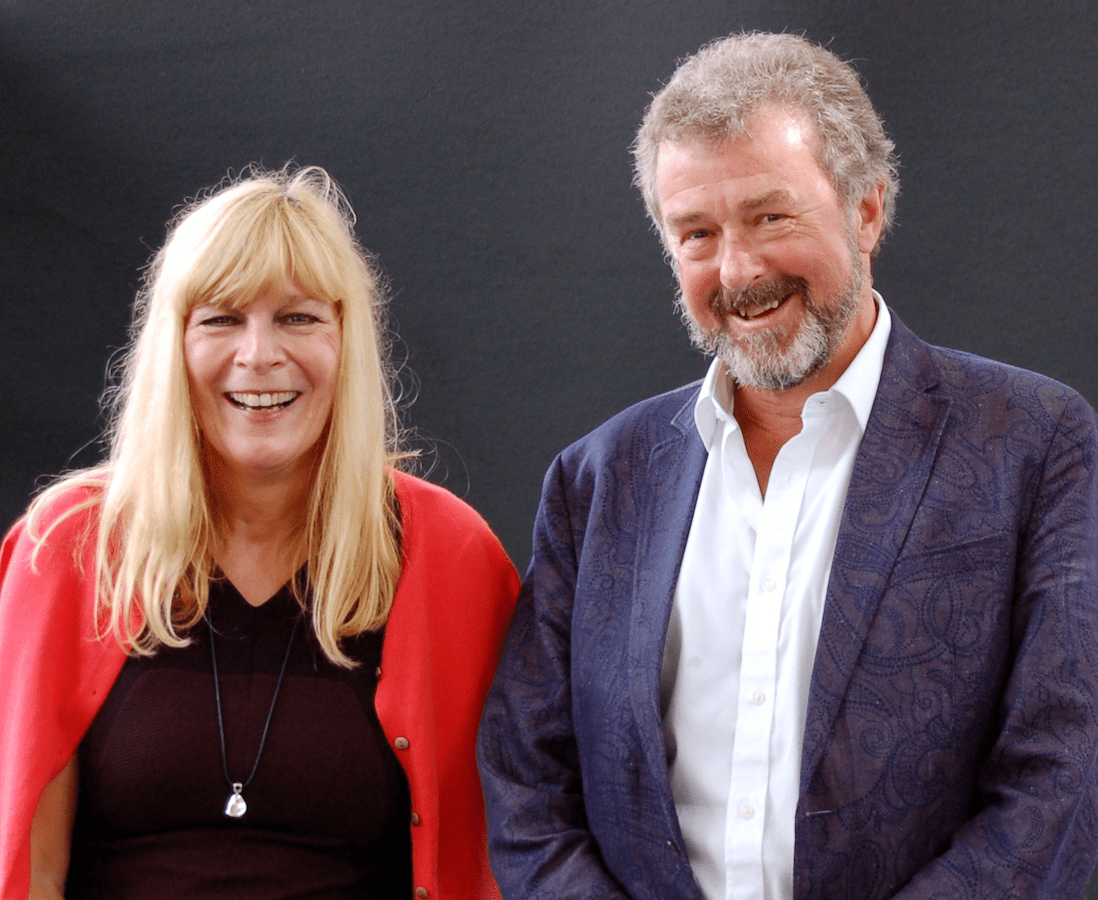

Josie Billington & Rick Rylance – Why Reading is Good for You

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Baillie Gifford Corner Theatre

23rd August 2017

In 1959 C.P. Snow, who was both a physical chemist and a novelist, delivered Cambridge University’s annual Rede Lecture, in which he spoke of the ‘two cultures’ of the humanities and the sciences, and how a gulf of mutual incomprehension had grown up between them. Today in the Corner Theatre we have been listening to speakers whose professional and academic efforts have continued both because of and despite that gap, in areas that have had a more than tangential relationship to the humanities in general and Literature in particular.

Josie Billington is Deputy Director of the Centre for Research into Reading at the University of Liverpool, and is also involved with the charity ‘The Reader’, which exists to facilitate reading groups where people who may be experiencing mental health issues can share readings of ‘great literature’. I have put quotation marks round that last term both to indicate that these are the exact words that appear on the web site of ‘The Reader’, and just to acknowledge that it is a term that has been challenged over the recent decades, though not today, Dr. Billington’s speciality being in the nineteenth century literary canon. Her recent book – and yes, this is an EIBF event so there has to be one – is entitled Is Literature Healthy? and it sets out the argument for the therapeutic value of reading.

Rick Rylance is Dean of the School of Advanced Study at the University of London, and Rector of the Institute of English Studies. Until recently he was also CEO of the UK’s Arts & Humanities Research Council, and his new book, Literature And The Public Good, comes from his experience as an advocate for culture and literature in particular to those who tread the thick-piled carpets of the corridors of power. Both Dr. Billington’s and Professor Rylance’s books are published by the Oxford University Press in a series of monographs entitled ‘The Literary Agenda’. The event was chaired by prominent Scottish GP and non-fiction writer Gavin Francis, who gave each of the main speakers ten minutes or so at the podium to explain the thrust of their books, before asking them for amplification of some of their points, and eventually moderating a brief Q&A.

Josie Billington spoke quite movingly about her work with The Reader, giving examples of literary texts that had voiced the inexpressible at the core of depression. There was a passage from Geroge Eliot’s Middlemarch, two lines by Christina Rossetti – “We lack, yet cannot fix upon the lack: / not this, nor that; yet somewhat, certainly.” – and two verses from John Clare’s ‘I am’. “Literature,” she said, “can make private and barely expressible things more personally felt and more publicly shareable.” A case in point was that of a reading group member who, on reading the verses by Clare, left the room for half an hour and, on coming back said “I need this language.”

Normalising the deep sadness that is often diagnosed and medicated as depression seemed to be the goal. I must confess to having mixed feelings about this, on the one hand being pleased for the therapeutic effect of literature on people who needed it, but on the other hand having to roll my eyes that something more than one person in my own family has fought very hard to have clinically diagnosed and taken seriously is now being brought back into ‘normality’.

Rick Rylance spoke of publishing and all associated enterprises accounting for seven percent of the UK’s Gross Domestic Product, being worth about £84bn per year, bigger than either the pharmaceutical or finance sectors. It is “a real and dynamic sector,” and culture in general lent the country diplomatic credibility and economic trust internationally. Reading is a mainstream activity, and “there is research that correlates ‘cultural participation’ with living longer.”

“Why,” he asked, “is cultural life in Britain, not least in policy circles and quite senior levels in government, seen as an add-on, a secondary phenomenon, a ‘nice-to-have-but-now-let’s-get-serious’?” A questioner from the floor suggested that the last thing the politically powerful wanted was the general population acquiring the kind of critical thinking that studying literature brings with it, to which he said this:

“My experience of Whitehall does not incline me to think that politicians are either the most intellectually or imaginatively generous individuals. They’re there for a quick fix, and they’re there for making a certain kind of impression, and to further their careers. None of that encourages me to believe they would be interested in critical thinking, because it requires a deal of work and reflection, and, frankly, knowledge […]” What worried him a little about the question, however was the idea that the humanities have a monopoly on critical thinking, when it was also a required and acquired skill of scientists and medics. “It’s a property of becoming intelligently informed, not of doing this discipline or that discipline.”

Despite the differences in the two speakers’ approaches to and uses of literature, they converged on many things. They saw literature as a ‘common possession’, and that it had to do not so much with private thought as with communication and transmission – economics and therefore politics could not grasp the way that the value inherent in a book, which may be lent or given away or discussed or used as a therapeutic aid, its concern with hopes and ambitions and emotions, is much more than its cover price.

There is also a problem with studying literature, however, when deep engagement or even pleasurable lightness, is sacrificed for “three or four talking points for an essay.”

Though other events this year may have given me a buzz through my being in the same room as a literary giant, this is the one which has engaged me most directly, the one which has been most intellectually stimulating and satisfying. Also I commend Dr. Billington and Professor Rylance for the clarity with which they argued their cases. I didn’t get an opportunity to buy either speaker’s book, but I may well do so at the next opportunity.

Reviewed by Paul Thompson

Richard English & Mark Muller Stuart – Does Terrorism Work?

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Garden Theatre

25th August 2017

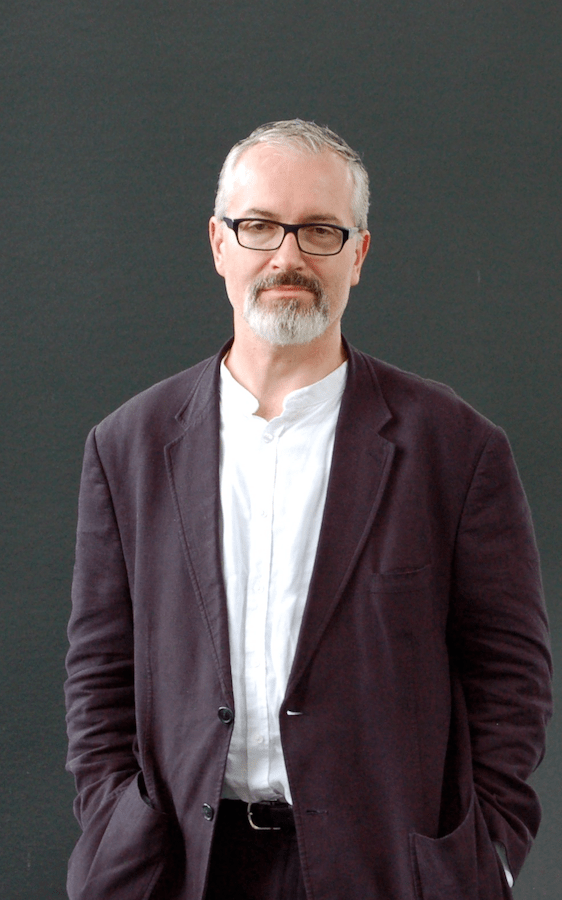

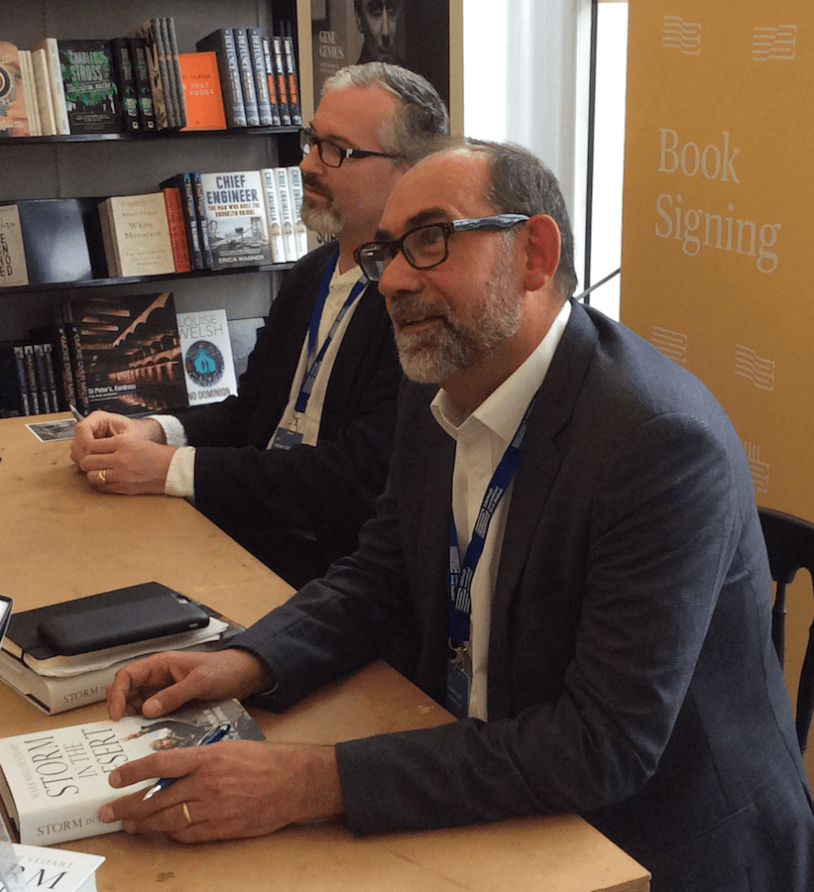

Today’s event here in the Garden Theatre was another one of those that punches above its weight. Sometimes the events with big ‘name’ writers can descend into chit-chat, which is entertaining in itself but can be froth rather than strong coffee. Events featuring distinguished academics or experts within a specialised field who do not, however, necessarily have the glitz and glamour of a celeb, are often where there is much more substance. Judge the weight of the two main speakers. Richard English is Professor of Politics at Queen’s University Belfast, and Distinguished Professorial Fellow in the Senator George J. Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice, and Fellow of so many other august bodies that our chairman, Australian broadcaster Michael Williams, had to apologise for not reading all of them out as we only had an hour available. Alongside, but by no means playing second fiddle, was Mark Muller Stuart QC, a distinguished Human Rights lawyer and expert in the ways in which negotiations with terrorists take place. The event itself shared its title with that of Professor English’s recent book – Does Terrorism Work?

Just a quick word about the way Michael Williams carried out his function. I had a chance to talk to him afterwards, and I commented that it had been bold to inject humour into the proceedings. For example, when he invited questions from the audience, he appealed for a female questioner, because so far, with three men talking on the stage, it had been ‘a sausage-fest’. He told me that he had seen his function as providing the ‘air’ in which the two main participants moved and operated. In fact this levity, almost flippancy, was no bad thing, as it prevented the whole event from going beyond seriousness into sombreness.

Michael first steered the talk to the issue of why it was necessary to ask this question – whether terrorism worked – at all, and Richard English was able to respond with a detailed yet condensed twofold answer. Terrorism, he said, is a way that people use to bring about socio-political change, and we can’t claim to understand the phenomenon of terrorism until we know whether it achieves that change, so there is an analytical value to the question. The practical value is that we are only able to respond appropriately to terrorism if we understand the ways in which it does or does not do what its practitioners intend it to do. Richard English was quick to state that of course it is not a popular question to ask – one reviewer described his book as “morally repellant” – and that the whole issue of ‘terrorism’ is often useful to people other than its practitioners, for example thrusting the label of ‘terrorism’ on a particular group can be an efficient way of closing down debate and suppressing discussion.

Mark Muller Stuart, in talking about how ‘non-state mediation’ came about, cited the post-9/11 ‘with-us-or-against-us’ paradigm put in place by President Bush and Tony Blair MP, which outsourced the definition of terrorism from the international community to individual states. The result of this was that it saw the definitions broaden to include any and all groups who used violence, or considered its necessity, to effect socio-political change. This in turn threw up all kinds of questions about issues such as the right to self-determination, which is defined under international law, and for which some leeway exists in that international law when it comes to resistance to oppression. This whole situation closed down the possibility of states or groups of states being involved directly in negotiations with movements they had outlawed, and made it necessary for those negotiations to be carried out in private by a body not associated with any state.

This was the substance of only the first ten minutes of the event, which will give you some idea of its intensity. Both main speakers talked very rapidly, but crucially they were clear-thinking and articulate, which means that nothing was lost, nothing passed the audience by.

I won’t attempt to summarise the rest of the session, but I will mention a couple of items that were brought up. Firstly Richard English made the point that research has indicated that the overwhelming majority of people who practice terrorism are, to all intents and purposes, normal, rational people – people with homes and families, with daily lives – rather than some kind of psychopath. They see, rightly or wrongly, violence as the only way to achieve a definite political aim. Far from being people to whom, according to the rhetoric of those they oppose, there is no point in or no moral justification for talking, it is often possible to end a campaign of violence without giving a terrorist group what it wants – Northern Ireland and the Basque region of Spain being two examples – but conceding something that the terrorists’ supposed constituency can be content with. A group such as ISIS, on whom there is much current media focus, is atypical, but that very media focus obscures the reality of other groups.

Secondly, in answer to a question from the audience about the female fighters in the cause of Kurdish Liberation, the point was made that the motivation behind their participation was often complex, and ranged from a belief in the cause itself to a wish to escape from a traditional life back home.

Both Richard English’s book Does Terrorism Work? and Mark Muller Stuart’s Storm In The Desert, about Britain’s intervention in Libya, are weighty, and neither is particularly cheap. But I now have a copy of each and I will reach for them. Several of Professor English’s lectures are available on YouTube, but I have decided to offer a link to a shorter piece by Mark Muller Stuart which he delivered to an audience in Glasgow last year.

This has been my last event at this year’s Edinburgh International Book Festival, I enjoyed it and the whole Festival immensely, and I’m already looking forward to more of the same next year.

Reviewed by Paul Thompson

Nikesh Shukla: Unwelcome Welcome

Edinburgh International Book Festival

August 15 2017

Bristol-based novelist and diversity activist Nikesh Shukla recently contributed to and edited the much-talked about book of essays and personal stories of 21 people of colour in the UK, The Good Immigrant. He leads a discussion with two of the contributors, Coco Khan and Miss L, which was informal and spirited. The book contains essays from many of the current leading lights of young culture and informed debate, including Riz Ahmed and Reni Eddo-Lodge. It was a sell-out talk, cheerfully and humorously chaired by Daniel Hahn, a writer and translator who was both shortlisted for and a judge for the Man Booker International Prize. In between some good-humoured jokes, he chaired an important and much-needed discussion in this Brexity climate of hostility towards immigrants.

Nikesh’s initial trigger for creating this collection was being invited to speak on a diversity panel on many occasions over a period of years, without seeing much progress in the acceptance and promotion of writers of colour within the publishing world in between. He yearned for the kind of book in the UK that we are seeing coming out of the USA discussing issues pertinent to people of colour in a racist society. He personally knew several great writers like Riz Ahmed that he could commission, and managed to raise funds easily through a Crowdfunding project, sidestepping the usual publishing routes with all its problems. The indignation at this sorry state of affairs comes through, rightly, without apology. And to the equally infuriating idea that now Blackness is ‘in’ and ‘cool’, he exasperatedly exclaimed, “It’s not a marketing trend, it’s our fucking lives!” Miss L is an actress of Asian origin and read her story ‘The Wife of a Terrorist”, about the disappointment of being typecast and held back by well meaning white tutors and audition judges. Coco Khan read us a hilarious and disturbing account of dating on the sly while living in a mainly Asian area of East London, and, as she put it bluntly, atttempting to get laid at her mainly white university just like everyone else, but running into problems being “Brown around Town”. Her own blog has helped to normalise and give a voice to young Muslim women navigating overlapping and sometimes conflicting subcultures within the U.K., and is now writing for the Guardian as well as other publications.

Nikesh said the book had two jobs; realising the power for people of colour in seeing themselves as visible, and for white people to fully humanise people of colour by realising the ‘universal experience’. Nikesh read his story ‘Namaste’, with its infuriation at cultural appropriation and the lack of respect for the origins of whatever trend happens to be fashionable and lucrative this season. The questions were from curious and concerned white people of various ages, who brought the discussion briefly to the burden of representation, getting past tokenism and what needed to be done in order to move forward. As expected, it comes down to the gatekeepers of power. In this case, who decides what gets commissioned, many of whom are benevolent but rather sheltered in their experience. Who perhaps unconsciously and unwittingly stand in the way because of their own preconceptions about people who don’t look or behave exactly like them. But there was no time to break this down further, which was a shame. We need details and strategy in this area to be able to fuel the kinds of ideas and momentum to move forward more swiftly.

It might just be a measure of my age, being at least 15 years older than the panel, but it did seem like many of the themes of the conversation among British people of colour were the same themes being discussed almost a generation ago, in the days when the theories of cultural theorist Stuart Hall were in the forefront. The difference, I think, this time, is perhaps the range of voices and the keen interest taken by the mainly white audience of all ages. In this, the book has served its purpose. At minimum, a solid platform has been created for people to have their voices heard, to express their frustration and disappointment at the systematic, structural racism that still unfortunately exists in this country. Are enough gatekeepers of power and the white consumers of culture listening and willing to move forward now? We will be all the richer for a true diversity of voices in a multicultural Britain where noone is made to feel like an unwelcome outsider, and there will no longer be any need for Nikesh to be wheeled out unwillingly to sit on another ‘diversity panel’. Because it will be completely normal to be accepted as fully British, whatever colour or religion you happen to be.

Reviewed by: Lisa Williams

Nalo Hopkinson, Ken MacLeod, Ada Palmer & Charles Stross: Rockets to Utopia?

Edinburgh Book Festival

August 18 2017

A panel of award-winning science and speculative fiction writers from both Scotland and the Americas blended their diverse perspectives for a fascinating conversation around speculative fictions imagining hopeful futures. Ada Palmer is a historian from Chicago who’s just published Seven Surrenders, the second in her Terra Ignota series. Jamaican-Canadian Nalo Hopkinson is the author of novels Sister Mine and many others. Representing Scotland were science fiction writers Ken MacLeod, author of many books including the Corporation Wars series and Leeds-born Edinburgh writer Charles Stross whose latest book is the Delirium Brief.

The Bosco Theatre is a circus style tent which is a new addition to the Book Festival, allowing its expansion into George Street. It can be noisy and a little distracting, as the tent flapped noisily in the breeze and allowed the sounds of Friday night revellers to intrude on the conversation. However the quality of the debate and the well-regulated and careful chairing by Pippa Goldschmidt made it a great experience. The first question to the panel from the chair was what each of them considered a utopia to be. Charles suggested that rather than a utopia being prescriptive, it was ‘simply’ an inverse of the golden mean; basically a system that minimized harm to others. Nalo referenced Thomas Moore’s Utopia, written in 1516 in Latin, and said she was suspicious about any utopia that included slavery in any form. That utopia was always an evolving process, which must include thought about how citizens can and should get along with each other. Ken used California as an example of a place that could be a utopia for some and a dystopia for others, with its over reliance on automation keeping us from our full destiny as useful and well-rounded humans. Amy agreed on the fact it was subjective, that it is necessarily a moving target because it has to feel better than our present reality to be regarded as a utopia.

The discussion moved on to how inclusive a utopia should be. It is generally regarded amongst science fiction authors and readers now that artificial intelligences should be afforded the same respect as human beings. Should this be anyone or anything the reader recognises as fully human? Or should we not anthropomorphize things or animals but just extend the boundary of what we should pay full respect? Did the authors feel a pressure or expectation of them as authors in this particular genre to explore and create visions of utopias? Nalo said she had her own personal expectations of herself in her writing. However, it was sometimes problematic. Using her novel Midnight Robber as an example, she suggested that the plot has to steer the characters into struggle and strife in order to fulfil the conventions and expectations of an exciting story. One strategy is for stories to take part outside the main culture, like in Star Wars, so that the utopia becomes as a reference point for any dystopia. Ken comes from a well known political background and his novels often reflect themes of exploring possibilities of communist and anarcho-capitalist ideas. He feels that there is a strong pressure to create the possibilities of utopia in people’s minds, seeing as it’s currently easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, drawing chuckles and agreement from the audience. He turned down involvement in a recent project for a graphic novel set in Scotland, as the rest of the contributors were fixated on imagining a ruined, flooded, dystopian Scotland, and he felt that he didn’t want to plant this in the imagination of young readers.

They broke down the distinction of utopia as either and adjective or a noun and took the examples of Orwell’s 1984 and the immensely popular Hunger Games series for young adults. Ken pressed the need to look carefully at the message of hope in the book, as although the Hunger Games is set in an extreme dystopia, the heroes successfully fight and win against it. They suggest the future of speculative fiction lies in looking at other cultures to bring fresh ideas and rework old mythologies, and that this kind of fiction often has to capture a particular point in time to be effective. Nalo discussed the impact of Japanese science fiction after the devastation and US occupation after the Second World War, featuring the iconic Astroboy, the original hero of science fiction. Intensely political, with utopian ideals prevailing despite a devastated landscape, but using veiled language to describe their oppressors. It was a unique generation involving international teamwork that gave it such a powerful focus. His name was even mentioned during a 2007 UN Peace conference, as people proclaimed ‘Let’s make a future that would not make Astroboy cry!’

The discussion moved to whether the role of science was essential in a utopia. Ken’s ideal being more of low tech ecotopia, where technology is necessarily limited, and work shared. However, in order to be credible for modern readers, it has to have a base level of necessary machinery to cut out the most difficult and energy-consuming labour. As they quoted historian Mary Beard, machinery for food production is indispensable, given our swelling world population, but brings up a very important question of who does the most disliked labour? Isn’t this the base of most of our inequalities and power struggles in all our societies? And what happens if a machine becomes your peer? Ken referenced William Morris as offering us a Marxist depiction of a utopia of a new England after a revolution. Nalo told us about her story Soul Case being influenced by the reality of the Quilombo, a Maroon (runaway slave) society in Brazil that managed to create not just an autonomous but a fully welcoming and inclusive society.

Ada points out the way that we draw on and feel nostalgic for certain periods in history is important, reminding us that the future is going to care about our present as it looks back in time, and decide why there should be a level of respect for ideas and arrangements of people in society. Nalo made the point that we should think about technology in a more expansive way to include song, which I thought was a fascinating idea. The elaborate systems of oral history that has been so important across the world in keeping traditions and history alive, is a technology in itself. As she suggested, if all the libraries burnt down, griots would be able to use the powerful medium and system of song to pass down history through the generations, placing its importance on a level with what we in the West refer to as ‘technology’.

Science fiction is a huge role to play in not just affecting politics but also inspiring scientists and social scientists, and a great way to discuss the ideas inherent in the concept of intersectionality. The audience members all looked liked they’d just left a meeting of Mensa, also asking further incisive and brilliant questions, and I was hugely inspired to start to delve in to the world of science fiction, joining the rest of the well informed, enthusiastic fans in the audience. I feel that I have been missing out for too long.

Reviewed by Lisa Williams

The Last Poets @ the EIBF

Bosco Theatre

23-08-17

Despite there having being a major war fought in the United States of America over the issue of slavery in the 1860s, over the next century or so, the Southern States in particular disenfranchised the free negro, using apartheid as a principle & divisory socio-politcal instrument. Cue Rosa Parks sitting on a bus, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, the Black Panthers &… The Last Poets. Springing from the vibewells of Harlem, several incarnations of the same ethos began to move & motivate the American mind. ‘Niggers are scared of Revolution,‘ they sang on their seminal first album, a call to arms which ultimately ended up in the Pax Obama. Considered as progenitors of hip-hop, they half-chant invective observations over a wild percussive sound, & work really well as socio-political sound-artists.

The Last Poets @ the EIBF consisted of a chit-chat with their pseudo-biographer, Christine Otten, a Dutch novelist who’d attached herself to both the mythomeme & the physical personages of The Last Poets, & created a novel about their story, rather than a conventional biography. This was published at first in Dutch, in 2004, it was only last year that it came out in English translation. ‘She’s a white, Dutch girl,’ said the Last Poets to inquisitive voices asking who the hell was this lady with an accent exploring the rock pools of their lives, ‘but she’s… OUR white, Dutch girl.’ During the talk, one could really feel that Otten’s presence was appreciated in the tight-knit world of the Last Poets, that she’d done a good job penetrating the egos, bringing out the humanity & telling ‘a decent story.’

The Last Poets – Baba Donn Babatune, Umar Bin Hassan & Abiodun Oyewole – are drifting back into the public consciousness, with a voice still resonant today – especially in the middle of all this Trump nonsense. After playing a gig in Edinburgh the previous night, the Last Poets are finally pouring their wisdom & love into the Scottish diaspora, & enjoying the experience immensely, comparing black subjugation to the English oppression of the Scots. So much so, that the talk spilled on for far longer than it should, but trying to get these guys off stage was hard work; neither they nor us wanted the moment to end, but when it inevitably did so, everyone just felt that little bit better leading & living their lives.

Reviewer : Damo

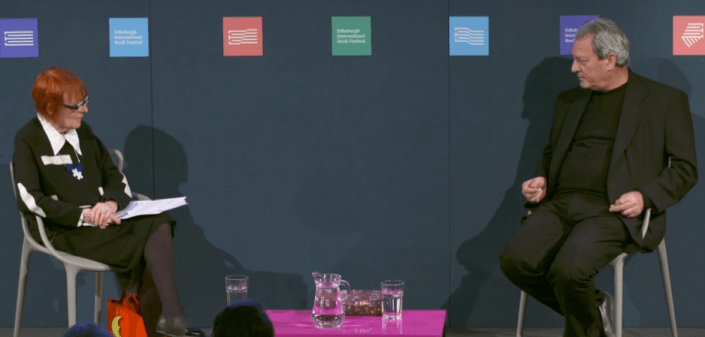

Paul Auster – New York Storyteller

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Baillie Gifford Main Theatre

18th August 2017

Cliché: ‘A giant of American Literature’. Justified: “he can out-Roth, out-Updike and out-Franzen the greatest” (Financial Times). I wrote earlier this week of selecting a flagship event for the Festival; well, unless I missed something else, this one would take a lot of beating. The sponsorship of the University of Edinburgh managed to net an appearance by an author for whom one can soon run out of superlatives. The problem of how to describe him doesn’t stop there. His first novel, The New York Trilogy…

Now hold on a minute! The New York Trilogy is a collection of three, separately-published novellas, only later gathered into a single volume. Start again. His first novella, City Of Glass…

Stop right there! What about Squeeze Play? That was published three years before City Of Glass. True, but under a different name. What is more, on being given a copy of both the trilogy and his latest book 4321 to sign by a fan this evening, he remarked very clearly “Ah, my first one and my latest one.”

And there we have (already) a wonderful set of contradictions, when it comes to Auster’s world. His real world and his fictional. The trilogy uses the genre of the detective novel not to unravel a mystery the way Hammett or Chandler or Paretsky might, but to raise questions about identity and reality, existentialism and the absurd, meaning and meaninglessness. 4321, not only his latest but his largest work, presents four parallel stories where the same protagonist (possibly) lives four separate lives (possibly) in the turbulent 1960s. City of Glass contains sparse, economic sentences such as “Quinn had been prepared for this and knew how to answer”. In 4321, however, Auster has mastered the perfect, long sentence, many of which last a whole paragraph, some of which seem to go on for pages; “I started writing a different kind of sentence,” Paul said. “It had a kind of propulsion, a paratactic urgency. I wanted to create a different tone.”

This event was sub-titled ‘New York Storyteller’. Every time Jackie McGlone, chairing the event, mentioned an aspect of his writing, or hinted at a question, Auster would take the topic, either squarely and obliquely, and run away somewhere with it. Often relevantly, often interestingly, always away. And always taking the listener along. A New York storyteller is precisely what Paul Auster is.

He read a long passage from 4321, in which he described Ferguson the protagonist (which one – does it matter at this stage? Not until we read the book in its entirety, and then it will become relevant, or so we hope) dealing with the certainty (to him) that the world and what was happening to it – the Vietnam War, International reaction, US politics, New York politics, campus politics, personal opinion and experience – was made up of concentric layers. The passage itself was fascinating, not only for its introduction of this mental impression, but the facts it was conveying, the people, the names, the organisations and their initials and acronyms, jocks and radicals, politicians and protesters, counter-protesters and cops, and every so often, almost without breaking the flow, Paul would insert a note of explanation for the Scottish audience, a footnote, a snippet of commentary. And it felt like part of the continuing storytelling. He also gave us the opening paragraph, which contains a piece of humour which depends on the reader knowing about the Ellis Island immigration process in 1900, and a little bit of Yiddish on top of that. In a way it’s an old story, but I won’t spoil its retelling for you. I will say that in order to appreciate a little piece of incidental humour, Google the Empress of China’s maiden voyage.

Jackie McGlone steered Paul onto the subject of politics and the current situation in the USA. Could anyone have come up with a fictional character like Donald Trump? Yes, Alfred Jarry, who created Ubu Roi in 1896, only without all the orange. Comparing the situation in America today with that of the 1960s, Paul referred back further than that, to the founding and expansion of the United States:

“We haven’t gotten anywhere, we’re just exactly where we were half a century ago. Nothing has changed. And then, you know, you start to question the very fundamental building blocks of the country. This great country of America is built on two crimes, two enormous sins – the extermination of the Indians and slavery of black people. And we’ve never really faced up to these things, never confronted them, and I think it has poisoned us, and now it’s coming out more and more and more again, another wave of racism and nationalism of the ugliest sort.”

“I can’t keep quiet. It’s too dangerous. It’s too serious to stand back and watch the country melt… A lot of the American system will be eroded by the time Trump leaves office. We need to keep beating the drum.” Paul admitted to being pessimistic, citing the way that Donald Trump had used Goebbels’ ‘Big Lie’ principle to slander Barack Obama, and by the time of the election he could utter any falsehood and would be trusted by the people who had come to heed him.

But of course, tempting though it is to harp on about the political situation in the United States, and though to do so caresses the confirmation bias of Brits who, like myself, do not like the political flavour of things there, this was supposed to be a literary event, we are supposed to remember what Paul said about his books, his low-tech methods of writing, his seven day working week, and our excitement at such a major work’s publication after an apparent gap of seven years. The solid ovation and the queue of people wanting books signed attested to that. The combination of the Festival, the University of Edinburgh, and the author delivered.

Reviewed by Paul Thompson

Penny Pepper

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Garden Theatre

18th August 2017

It must be daunting to face an audience, even a small one at one of the Festival’s smaller venues, but to have to do so on one’s own because the person who was due to share the stage has had to pull out takes a lot of nerve. It would have been fascinating to have seen and heard iO Tillett Wright, but – let’s face it – Penny Pepper is now a veteran of appearing in public, having emerged from behind the pen name of Kata Colbert many years ago to become both a poet-performer and an advocate for people with disabilities, and if anyone could carry it off she could. I think this does challenge the Festival programming; a joint Wright/Pepper event would have been in interesting mini-colloquium, but either one of them could easily fill an hour with something unique.

Penny was primed and prompted by poet Ryan van Winkle (and yes, that is his real name), whose enthusiasm did occasionally cause him to talk over her more than a host should, but I’m guessing that was his delight in being there. It’s picky of me to mention it, I know, and by-and-large he did all that a host should do at one of these presentations.

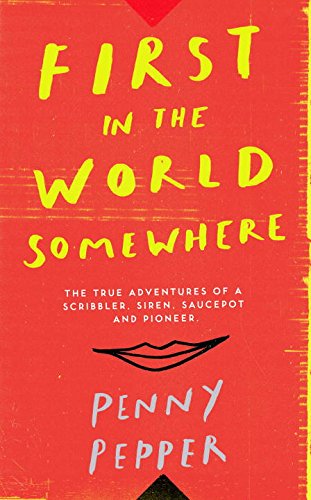

With the rain beating on the roof of the Garden Theatre, Penny read from her new book of memoirs, First In The World Somewhere. She has been an avid diarist for most of her life, and each section of the book, she told us, is introduced by a few lines from her journal. Such is the style in which she has written this – narrative, almost prose-poetry in places, the first passage she read out interrupted by curses and racist comments from her stepfather – that it was impossible to say where the journal extract ended and the creative memoir started.

Although Penny has happy memories of her father (still alive when she was a child) teaching her to read before she went to school, ‘home’ eventually became, in her words “a prison, Hell.” She did not want to live “the designated life of the cripple,” and so, full of Sex-Pistols-fuelled rebellion, decided to move from her rural home to an independent life in London. This took extraordinary self-belief because, as she told us, even the language of independence for the disabled did not exist back in the 1980s. One way of taking hold of her own life was to show off in her choice of clothing. Breaking out of stereotyping was also a way that a disabled person could express “a universal experience,” talk about love, sex, fun, even write to the Pope (yes, she did that – it’s a long story and I hope you hear it straight from the poet’s mouth some time).

The late seventies and early eighties was the height of the era of the fanzine. That’s a concept that the blogging generation would be hard put to get its head round, but this medium of do-it-yourself, audience-participation samizdat was where ‘Kata Colbert’ first emerged. A letter of hers was ‘Star Letter’ in Jamming magazine, and she issued a poetry cassette under the title of ‘My Heart Is Like A Singing Bird’ – she owned up to us that titled was borrowed from Christina Rossetti.

Ryan van Winkle quoted her as saying that “‘crip sex’ is still a taboo,” to which she replied “The taboo is a social construct… the body perfect is a construct… My bottom line is be human, it’s a human issue.” She also rejects, as a construct, the ‘charity model’ of disability, with its implication of gratefulness on the part of the recipient. She talked about having addressed the House of Lords and served on all kinds of diversity panels, notwithstanding her objection to the construct and the expectation that largesse was something to be handed down to the grateful. She talked about her good friend the actor Liz Carr, about Margaret Thatcher, about St Francis of Assisi (she was delighted with the idea that the birds he preached to might have been the carrion-eaters on the city dump when he became disillusioned with the people of Assisi), about her best friend Tamsin, about boyfriends, about Bill Grundy interviewing the Sex Pistols, and lots more.

If I have one… well… not a complaint but a regret, it’s that because the event was to promote her memoirs we didn’t get to hear her poetry. But there’ll be plenty of other opportunities to do that. Check your local What’s On! I had a chance to chat to Penny afterwards, and that was fascinating because she is utterly charming and much more approachable than some Festival celebs, but our chat is not what this review is about. Many thanks to Penny, to Ryan, and to the EIBF for allowing us to spend an hour with her.

Afterthought: do you realise that Penny Pepper has no Wikipedia entry? Get that sorted, someone.

Reviewed by Paul Thompson

David Olusoga @ The EIBF

Thursday 17th August

David Olusoga is a rather handsome mixed-race gentleman – half-Geordie, half-Nigerian – who has recently blazed an educatory trail of enlightenment across the world. His mission has been a continuation of the salvage jobs on black history made a generation previously by historians such as Peter Fryer. Through these joint efforts, the invisible voices of the African diaspora that permeated the white world, often brutalised by chains, are given at least some breath. The core of Olusoga’s directive is that there is something of a watershed moment taught to all our children, that British history remembers only the abolition of slavery, & chooses to ignore the desperate unholy years before emancipation. The same classroom texts are also stuffed full of spinning jennies & factory chimneys, but nowhere do we read of the cotton fields of America which were the lifeblood of the Industrial Revolution.

David Olusoga is a rather handsome mixed-race gentleman – half-Geordie, half-Nigerian – who has recently blazed an educatory trail of enlightenment across the world. His mission has been a continuation of the salvage jobs on black history made a generation previously by historians such as Peter Fryer. Through these joint efforts, the invisible voices of the African diaspora that permeated the white world, often brutalised by chains, are given at least some breath. The core of Olusoga’s directive is that there is something of a watershed moment taught to all our children, that British history remembers only the abolition of slavery, & chooses to ignore the desperate unholy years before emancipation. The same classroom texts are also stuffed full of spinning jennies & factory chimneys, but nowhere do we read of the cotton fields of America which were the lifeblood of the Industrial Revolution.

Olusoga is a man of spring temperament; charming, gentile, soft spoken, he expertly wove a comprehensive tapestry of his subject matter for a packed house. Then came the thirty minute Q&A, all chaired consummately by Celeste-Marie Bernier, & it turned out that Olusoga has almost accepted defeat, that the classroom is not the place to educate our future generations on black British history, but we should leave it instead to demographics, & perhaps TV programs such as the ones he produces on the subjects. This left an unusual aftertaste, for when something vitally important needed doing about rewriting black history, Olusoga actually did it, but has then almost lost faith in what he has done. Even so, the forest of hands that remained straining at the end of the Q&A is proof that there is a lot more debate to come on black history, & it is through passionate historians like Olusoga & those to come that this will hopefully occur.

Reviewer : Damo

The Power of Translation: Nick Barley introduces Daniel Hahn, Kari Dickson, and Misha Hoekstra

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Garden Theatre, Charlotte Sq.

16th August 2017

Many events at the Edinburgh International Book Festival are hard to ignore. In some respects picking events to go to is rather like sifting through a longlist, narrowing it down to a shortlist, and deciding who gets the prize of your attendance. We all have our own views about what is, or was, or will the best event this year. However, when a contending event is chaired by the Director of the Festival, who was also the Chairman of the 2017 Man Booker International Prize panel, and the event includes a fellow judge who happens to be the Festival’s go-to-guy in matters of translation, and one of the other participants translated one of the shortlisted books, AND the remaining participant is a fine translator in her own right (reviewer pauses here for breath), that event has to be on the mother of all shortlists.

Setting aside the issue of whether literary prizes help perpetuate an attitude to fiction where gatekeepers tell us what is and is not ‘literary fiction’ as opposed to popular fiction, this event was outstanding for the way it gave an insight into the art and science of translating. It was so fascinating that by one third of the way though I forgot I had to review it and found I had stopped taking notes. So what follows are impressions. This will not be the last time I will say this, but an hour, with forty-five minutes of chaired talk and fifteen of questions and answers is too little for events like this. On the other hand, the audience leaves with its curiosity whetted and a book or two on their shopping list. Nick Barley, in the chair, steered things with great ease, and the early intervention of a question from the auditorium about dialect enabled him to bring that very issue to Kari Dickson, who recently worked on a Norwegian text full of dialect. The Norwegian language exists without the burden, some would say, of a ‘Received Standard’ version. The country’s population is roughly the same as Scotland’s, but spread out over much further. Every town – every village, every valley, according to Kari – has its own dialect, and all are regarded as valid ways of speaking Norwegian. But translating a remote Norwegian dialect into English is a different matter. In the UK dialect and accent are the fuel of value judgments. So rather than translate into an identifiable dialect from a British region, Kari chose to construct one. That’s not without its problems when, in two adjacent lines, someone shouts “A want t’fuck,” which looks as though it ought to be Lancashire-speak, and someone says ‘thar’ for ‘there’, which seems distinctly Appalachian.

The problem of whether to translate a well-known Danish phrase by using its well-known British equivalent was also raised. Misha Hoekstra translated Dorthe Nors’s Man-Booker shortlisted Mirror, Shoulder, Signal. Those words are a precise translation of how learner drivers are taught the skill of turning in Denmark. So why not call the translation ‘Mirror, Signal, Manoeuvre’? The answer is that the English translation also goes on sale in North America, where the routine for turning a car is taught differently again. So the decision was made to stick to a direct translation. But then there was how to render the idea of a pedestrian crossing – in the end that became the transatlantic ‘crosswalk’.

Misha and Kari gave us readings in Norwegian and Danish, and if beforehand we had been tempted to think of all Norse languages as being somehow interchangeable, hearing them spoken in juxtaposition highlighted their differences in sound and cadence.

Perhaps the ‘star of the show’ – if that is a valid description – was Daniel Hahn. He is no stranger to the Festival, and when asked to speak about the books that had made it onto the Man Booker International shortlist he spoke rapidly, fluently, and clearly. If there was anything I would liked to have time to ask him directly, it would have been a follow-up to his remark in answer to a question from the audience about punctuation. The questioner had noticed a difference between the speech marks used in Norwegian and English texts. Although the question had been directed to Kari, Daniel intervened to say that the practice was to aim for the most ‘neutral’ usage in the target language. It had been in my mind to ask about the danger of assuming that the target language in a translation, particularly if it is the translator’s own, is somehow a neutral medium. But I didn’t get the chance to ask it, and it didn’t really matter.

Yes, these sessions often seem to short, and yes they often raise more questions than they answer, but that’s no bad thing. And as long as the Festival keeps serving up events like this, I’ll be only to happy to go along to them.

Reviewed by Paul Thompson

Teju Cole: Blind Spot

Edinburgh Book Festival

13th August 2017

Teju Cole is hard to pin down into a category, and I expect he likes it that way. An award-laden Nigerian-American author, photographer, art historian and critic, including for the New York Times, Teju was talking with Chicagoan Elizabeth Reeder, currently Lecturer in English and Creative Writing at Glasgow University. The hour began with photographs from his new book displayed on the screen, as he read the poetic and intriguing text that accompanied each one. It’s a huge, 300-page tome of both photographs and accompanying text, which takes longer to read than a novel of similar length due to the time taken to study and reflect on each image. He’s the author of four books, seemingly unrelated, but actually forming a loose quartet of themes. Reeder talked about Cole’s circular technique of ‘return’, looking at something again and again to explore it in a different or deeper way, similar to the spiral-like structure of Toni Morrison’s more complex novels.

The images ranged from a young boy in sea water wearing a black glove, eerie simple wooden crosses at the US-Mexican border, a potentially ominous water standpipe in Brooklyn, scenes in London, Lagos and the French countryside. He lets us see these snaps of life through his personal lens, anchoring each one with a snippet of story, history and meaning; the pathos of the the disabled daughter like ‘an astronaut far away from home’, and the beauty of ‘the bunting of vintners’ blue nets’. The name Blind Spot plays on several ideas. The lack of meaningful reference points, our blind spots when looking at unfamiliar peoples and places that are barely, superficially or falsely represented in the mainstream. Cole’s own brush with temporary blindness in 2011, which no doubt spawned a renewed appreciation for the gift of sight, and a sense of double vision; looking outward and inward at the same time. Because he is a multi-media artist, when his work is in a gallery, he is able to play with form, structure and logic to different effects, and may just compress his show into just 7 chosen slides. He’s open to new forms, including live performance, depending on whatever channel the work needs to express itself through, and has been inspired greatly by film.

Cole regularly revisits, in his own words, several particular themes. Human fragility and the uncertainty of the body, issues of faith and religion, and thirdly, political tension, and quotes the enduring influence of Homer’s Iliad on his world view and art. Because he is both a photography critic and photographer, one set of skills and knowledge intimately affects the other. He admits that the text can both explicate and complicate, which provoked of the audience members to ask for more explanation. “I don’t know,” he said with a smile, “I could just make something up.” He suggests that having words with pictures forces the viewer to slow down and gaze at the pictures for longer, even though he humbly suggests that the images themselves are “aggressively banal”.

Reeder wondered about travel and how it informs his work. He said the work was never about travel per se, but more “how to go to places and be completely depressed”, making his the anti-travel memoir. He explained that although certain symbols have become instantly recognisable symbols of a place, acting to supposedly differentiate it from other places was often actually false representation, being only espoused by a tiny minority. Scottish men in kilts, for instance. He prefers to look under the surface and find the essential differences in the history of what created the peculiarities of that particular place, precisely because each place has a vested interest in suppressing its own history.

Yet the love for the art forms themselves is strong. As well as to make people think in new ways, his goal is also creating pleasure. His satisfaction comes from the fact he is able to shape and prepare an experience for the reader/viewer. Just like a pianist playing legato, where the flow of the notes creates the beauty and the feeling of pleasure, good writing does exactly the same. His metaphors and worldview lean to his Nigerian background and culturally holistic patterns of thought and debate, such as allowing ‘windows for spirits to get in and out’. We’re keenly aware that we are just being allowed a peep into his vast, hidden depths and wish he could continue in his humble and softly-spoken way, with what he finds most difficult and we find so wildly compelling; ‘making his vulnerability formal’.

Reviewed by: Lisa Williams