Adventures on an Indian Visa (week 13): Visakhapatnam

Day 85

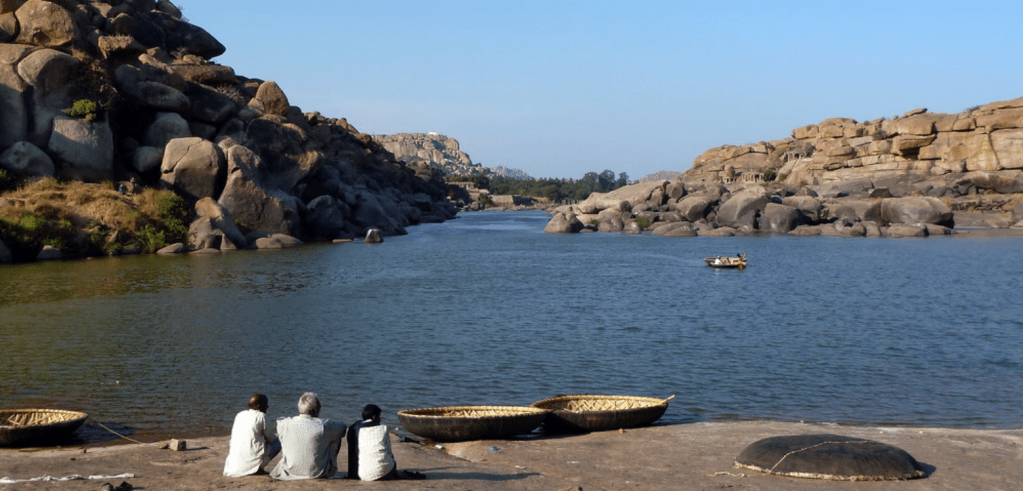

My first full day in the Telegu-speaking Visakhapatnam, or Vizag for short, was pretty cool. I like the vibes of the place. It turns out the cityhad beens conquer’d by the Vijayanagara Empire in the 15th century, i.e. it was ruled from Hampi, & so I felt some natural kinship already.

On joining in my obligatory, get-to-know-the-locals cricket game with some young Indians, I was befriended by seventeen-year-old Sameer. He was a likeable chap & very keen to hear of life in the West. He’s a Muslim to boot, & invited me to his house in the old port quarter of Vizag to meet his parents, who were quite simply lovely, & fed me like a trooper. Its mad, they literally all live off sixty quid a month – & Sameer just receiev’d a student grant for the same amount to last the whole year.

He & his sister are quite academic – hoping for better lives I guess – & we even discuss’d Shakespeare. It amazes me how the young Indian ploughs through the complex densities of Shakespeare like dull oxes ploughing the tough soil of Elizabethan English. However, seeing as they speak four languages fluently – Urdu at home, Telegu in the street, English at school & Hindi to other Indians – I guess they can handle the obscurer corners of Shakespeare’s lexicon.

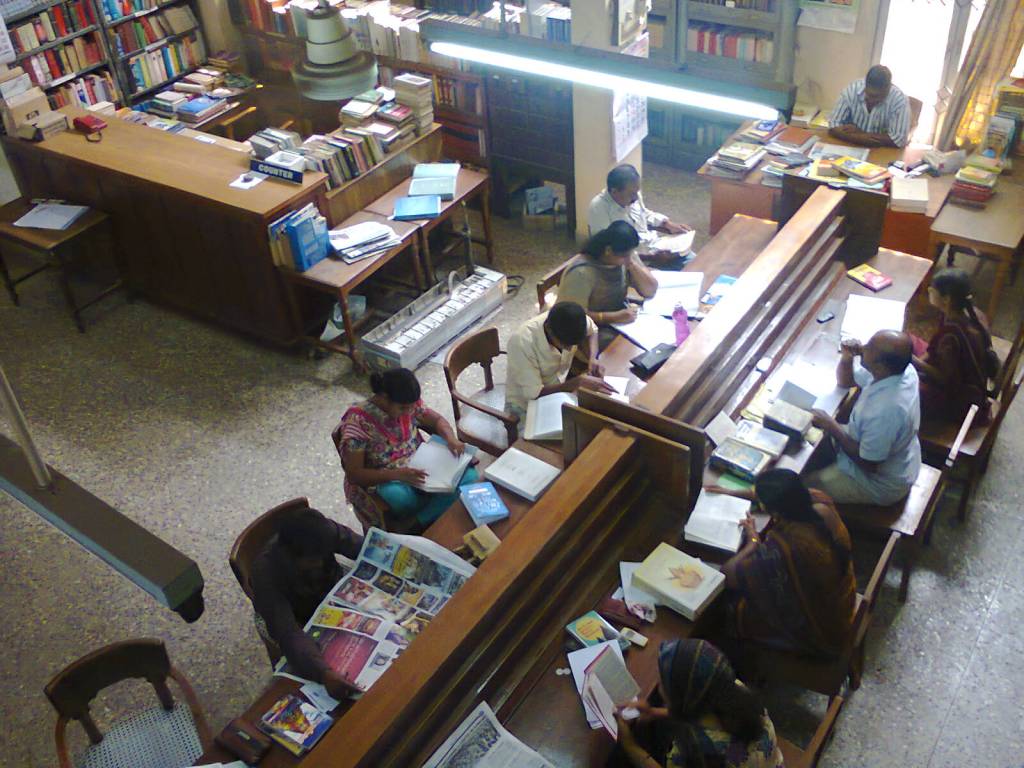

After a congenial couple of hours, Sameer then pointed me toward the only library in town. Ran by the Ramakrishna Movement’s ashram, it flew like an angel into my literary lap. It’s time to get mi head down & absorb this wonderful country thro’ words, as well as experience.

Day 86

Woke early to a glorious morning! Being so motivated by the weather & my exotic location, I attun’d myself to my vocation & plugg’d into the universe, setting myself some kind of daily routine, which has just been conducted thus:

5.30 AM: Wake up

6 AM: Walk to train station to get English newspaper, calling for poori breakfast on the way back

7 AM: Watch movies in bed playing guess the swear words – they silence the voice & put stars where the word should be on the subtitles. Despite being English language films, I think they put English subtitles in to help Indians learn the language.

10 AM: Internet café for an hour of work

Midday: Lunch

1 PM: walk to an internet place near the sea for a couple more hours of work

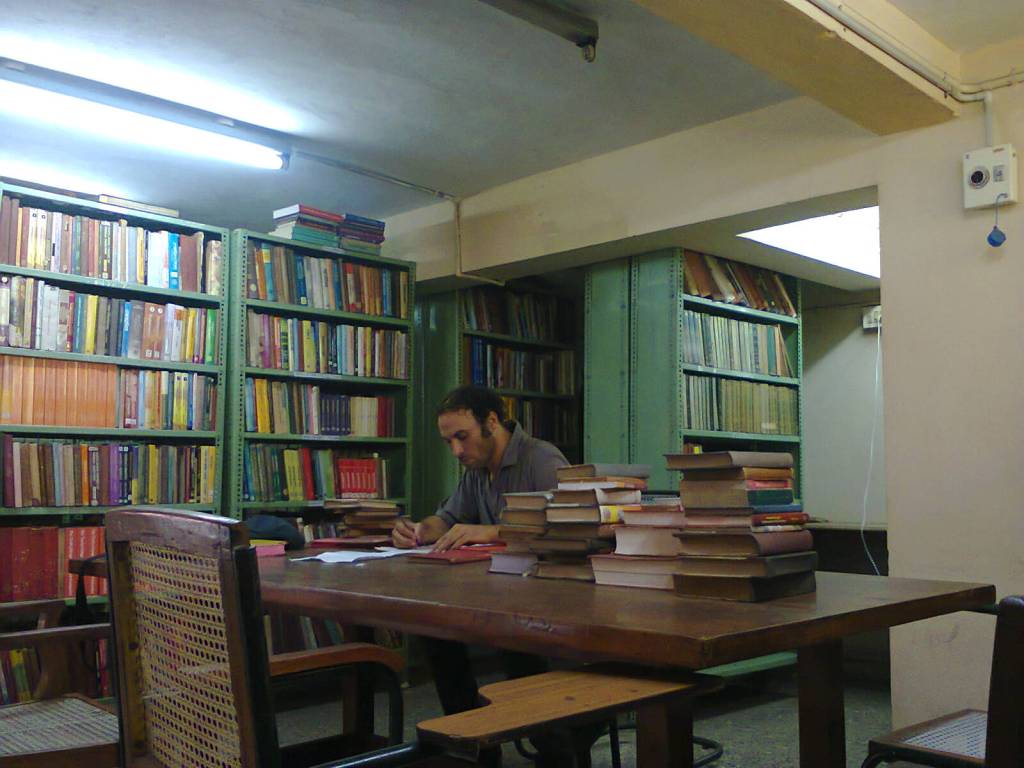

4 PM: The library opens where I hit the books – but only one at a time. They are all held behind locked up glass cabinets, & you have to sign each book in & out every time you use it. The library is on the beach road & my session is divided by trips to the kiosks on the beach for these beautiful samosas & ice cream cornets

8 PM: Walk back to my hotel, chomping on various street foods as I go

9 PM: Two & a Half Men on TV for several episodes, cups of tea, & sleep

Day 87

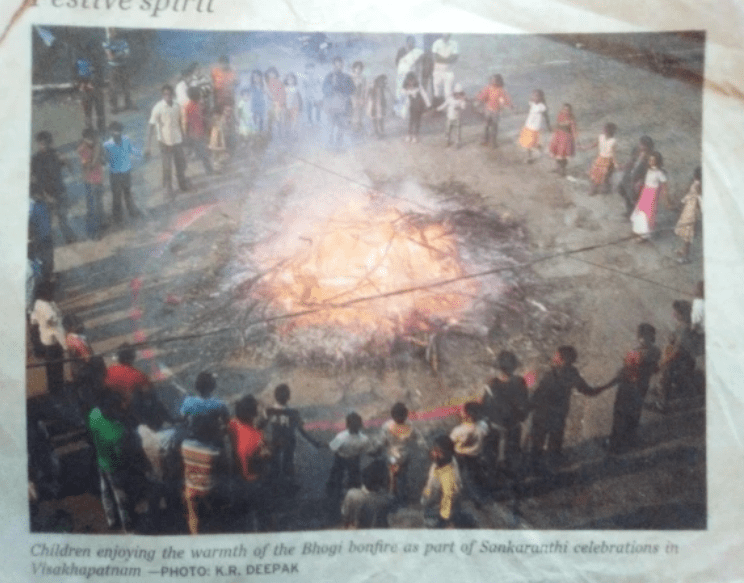

I have just play’d witness to the rather colourful Sankranti festivities of Andhra Pradesh. They are spread out over three days & are just so cool to wander about in. Today, the first day, was called Bhogi, which began at the unearthly hour of 4 AM. It is then that fires are lit across the city to banish evil spirits in the same way we burn sage when exorcising a house. I duly set off out into the darkness at four, & went on a tour of the neighbourhood’s ‘bhogi’ bonfires. The first one was just a guy on his own burning two four-by-fours in a shack, his mate snoring beside him. The second was a largish affair of long poles – but the clientele were clearly ruffians, one of whom was being beaten with a brush by an ancient woman half his size defending a bit of rope netting.

The third fire was a wee one, with a lone man boiling a large pot of water. Nearby was a chai stall doing its first business of the day, & by him a guy standing in front of piles of blue crates full of plastic sacks of pasteurised milk. The fourth fire looked like an oil drum, burning by a temple, but on nearing it I realised that it was a load of rubber tyres stacked in a tower, with wood inside it, belching off thick black smoke. The fifth fire was a family affair, at the crossroads of two narrow, Mediterranean-style streets, dominated by this fat controller guy who kept bringing wood out from nowhere to add to his massive pile.

The festivities were disturbed regularly by rickshaws & scooters trying to squeeze thro’ gaps in the road. Walking down the street I pass’d some startlingly psychedelic patterns chalked outside the houses. Then further on, the sixth fire burnt above me – on a bit of concrete sticking out from a half-built house. There was no-one sat by it, but it added to the scene. The seventh fire was on a mainish road, by a temple to Durga – the goddess perched on a tyger – & was predominantly women. I thought this would be a good place to stop, then, with seven being such an auspicious number; the Hindus have seven holy cities, rivers, etc, & the chicks were kinda hot too! This fire was pretty big & was built within a chalk circle, coloured in with flowers at the points of the triangles that formed the circle like Nepalese peace flags. I shared the moment with a Western girl from Luxembourg (her German boyfriend was asleep) & we silently watch’d the great pieces of wood turn reptilian in the flames.

From then it was pretty much the same routine as yesterday, but of course passing thro’ streets full of burning embers. At the end of it I got an email from Charlie. He’s doing very well, apparently, writing his memoirs or summat. Anyway, the plan is to meet him in a place call’d Puri in a couple of weeks or so, which is north of here in the state of Orissa. From there we’ll hit Calcutta then head up to the Himalayas together – should be fun now he’s calm’d down somewhat!

Day 88

A blazing hot morning on the second Sankranti day, the events of which celebration made the sky resemble a multi-coloured spectrum of wafting confetti, with paper birds filling the azure spaces over the city like the Luftwaffe over London during the Blitz. In the middle of all the smiling kids, however, I got myself all poignant. There was this sad wreck of a man sleeping – shaking actually – on the pavement. Perhaps he was dreaming of a time when he ran tho’ the streets with his own Sankranti kite as an innocent, fun-loving boy, long before life struck him to so lowly a state.

On Vizag’s promenade there is a cool monument with tanks & planes & even a submarine, which is a memorial to this war India had in 1971. I’ve never actually heard of it before. It only officially lasted a couple of weeks, but up in Kashmir has never really stopp’d, with frequent skirmishes over the LOC (Line of Control) established at the end of the war. One of the results was the establishment of Bangladesh, the former East Pakistan, which now broke away from Pakistan. In the months leading up to the conflict, the Pakistanis were proper rapist butchers, so it was definitely a good war to fight. In announcing the Pakistani surrender, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared in the Indian Parliament:

Dacca is now the free capital of a free country. We hail the people of Bangladesh in their hour of triumph. All nations who value the human spirit will recognise it as a significant milestone in man’s quest for liberty.

The last part of the Sankranti festivities occurred with a mad street party thrown to the local tutelary deity, Lord Balaje, a curious little black fellow who one sees everywhere. It was a bit like Notting Hill Carnival, & indeed there were loads of speakers belting out tunes top volume to the heaving mass of Indians wandering thro’ the streets. A street was lit up Blackpool illuminations style, with dolphins & green bars puking illuminous light onto the scene. All the kids had these wee vuvela things which gave out a dreadful shrieking sound – a bit like one of mi exes having a strop. There were loads of stalls – porcelain dolls of the gods, sugar cane – & a heavily decorated ox (called a gangireddulu) getting all four legs onto a little wooden stool while his keepers played drums & trumpet. There were cardboard boxes of chicken chicks spray-painted in pastel colours, there was a guy with a set of weighing scales charging a rupee a pop. There were corn-on-the-cob sellers fanning the cobs over hot coals – I tried one & it was very tasty indeed!

Day 89

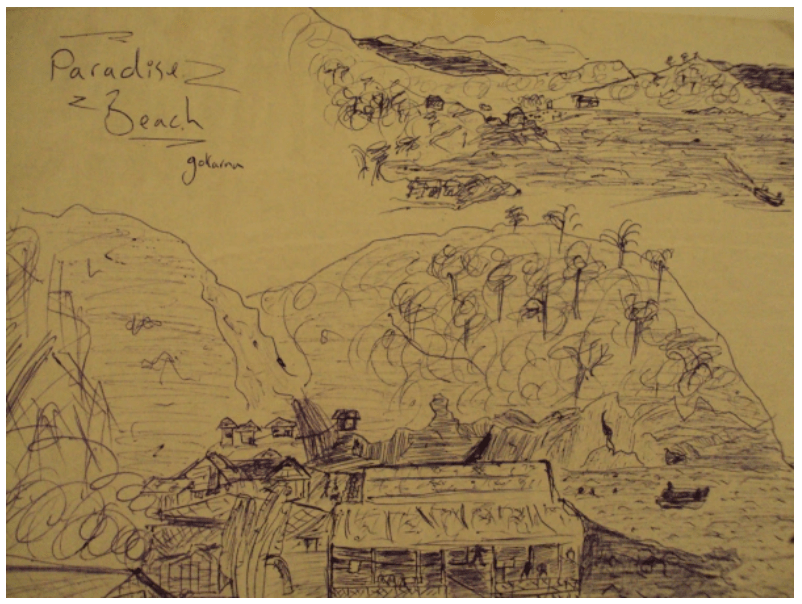

This was going to be my last day in Vizag before I set off north, so I thought I’d get back in the travel zone on the trains – I haven’t been on one since I pull’d into Chennai a couple of weeks back. So, I thought I’d have a little practice run, & this morning I found myself 15K north of Vizag at a place called Thotlakonda, a hill which houses the ruins of a 2000-year-old Buddhist complex. They weren’t particularly impressive, but the views were, of the gold-lined ocean below & the rolling upland greenery of the Eastern Ghats behind. The road to sea level was lined with blossoming trees, a very lovely walk which recharged the poet in me. At the foot of the hill I caught a bus which swept me along the ocean drive back to Vizag – which strangely enough felt like home.

With is being such a lovely poet’s day, I suddenly began to formulate a hybrid kind of sonnet using the Sanskrit measure I was studying in the library, which I’ll use as the mould for my Orissan experience – that’s, 15,16, 17 syllables worth of line. Here’s my first effort using the ‘Indian Sonnet’ form;

THOTLAKONDA

I’d been studying at the Swami Vivekananda library

Of how the tumbling Sanskrit couplet first utter’d by Valmeeki

& so, choosing its nuances to explore in composition

I left Vizag’s fair vibrancy on a morning’s musing’s mission

With my subject now the Buddha, or at least his teeming influence

I’m certain Jesus merg’d his teachings at an eastern confluence

Boneshaking bus pass’d Rushikund, tree-fill’d beaches, Goan hills,

& dropp’d me off at the colourful foot of Mangamaripeta

From where I climb’d a pleasant hill flank’d by pretty pastel blossom

Another Lingala Konda, another Gopalapatnam

Stood red & ruin’d where Ashvaghosha’s plays were once enacted

& like the Hill of Pigeons, the sacred rains cistern extracted

With views of hills & skies, & the breeze & an ocean sunrise

Far from Siddhartha’s vision, an aloofness to aid his demise.

So after preparing loads of notes for my poetic cruise around Orissa, I shall be starting in earnest at 6.50 in the morning. I’ve got to conduct a six-hour train journey through apparently beautiful scenery, including passing thro’ the highest train station in Asia. Cool! I’ve got my rough route worked out & one of the places I’ll be calling in on is a Maoist hot-bed. They are a secessionist group who have been fighting for their rights & lands against, well, less the Indian government, more the corporate conglomerates.

The bodies keep coming out of the forest. Slain policemen wrapped in the national flag; slain maoists, displayed like hunters trophies, their wrists & ankles lashed to bamboo poles

Arundhati Roy

Sounds like an awful lot of fun!

DAY 90

This morning I left Vizag by train, steadily climbing up the west side of the wooded Aruka valley, with the views growing spectacular by degrees. Every time we hit a tunnel, a huge cacophony of screams & yelps uttered forth from the Indians – in the end I realised they were playing with the tunnels echo-systems. After a few hours we hit Asia’s former highest railway station, Shimilguda, at 997 meters above sea level. It was usurped of the honour in 2004 by, I’m guessing, the express railway that links China & Tibet. From there began the steady drop into Orissa & Jeypore thro’ a landscape which look’d increasingly like the Highlands of Scotland.

ENTERING ORISSA

As I railway’d out of Vizag for to write poetically

Verses concerning Kalingan Kings mix’d with state modernity

Above breathtaking beauties, rising on the valley’s western side

More stunning than the Niligris, only a mile or more wide

A thick white bank of fog & cloud eagerly envelop’d the line

& I found it very wonderful for this world, sweet world, still mine

I’d nearly died on Andaman, but today my eyes were seeing

By Boddavara, steep hill-slopes perfect for a spot of skiing

But far too lush vegetation, as if the Cumberland fells

Had time-warp’d through to Jurassic days, as today the tunnel yells

Of giddy kids exhilarates climbing to Shimiliguda

Asia’s former highest station, a summerhouse for Garuda,

Beyond Aruka, scenery seems less savage Scottish sister,

We sierra thro this Spanish spaciousness of South Orissa

After the comfortable hotel at Vizag I’ve opted for a bachelor’s lodge in Jeypore; with my decent but basic room costing a quid a night. It’s a bit noisy at times, but I like the fact there’s no TV – a lot more conducive to literary endeavouring. This mental peace, however, was counter’d by experiencing the JAI CHITTAMALA Music Band Party. Witness a ramshackle sound system on four wee carts being dragged through the streets of Jeypore. On the heavily decorated carts were speakers & generators, plus a techno style djembi player & an eight-pad electro drum kit player. Providing the music was this cross-legged moustached guy & a Yamaha keyboard playing all sorts of celestial swirling sounds.

Walking alongside were a couple of singers, huddled like MCs at a rave. One was about eighteen, & his groove-surfing melodies were better than both Ian Brown’s & my own voice put together! Amazing stuff. On both sides of the carts were an assortment of snare players & trumpeteers, while directly in front & behind were the dancers. In front were a bunch of wee boys pulling off some amazing moves including cartwheels, while at the back were all the older men doing a lot of stuff with their hands. To the side of these were all the women, slowly walking & made up to the gorgeous Indian max – very hot – including the curious nose-bling that Orissa seems to be the home of. Behind them rode the reason for all this fun & frolics, a very handsome man, again decorated wonderfully, sat in an ambassador car, either on his way to, or coming back from, his wedding. The whole experience compell’d me to pen the following sonnet.

MANI WEDS SUKANTA

A wedding is a display of wealth in the garb of showcasing our culture

Ranee Kumar

It begins with an advert, on the internet increasingly

& discreet meetings to appease, spreading concord through each family

Then a swirling bull of energy erupts in flashing lights

Emanating from the envelopes of seven hundred invites

When disco beats down lane & street leads the groom thro Sakhipara

To his deer-eyed, lotus face of a bride, opening with mascara

It is a beautiful ceremony on an auspicious day

The priest presents which parts of the Vedas in Sanskrit he should say

Their hands are bound, happy promise of prosperity & children

Then the newly-weds share their joy midst many benign presences

Where women shimmer glamorous as the lads dance with aplomb

All hoping to avoid the pitfalls of Matrimony.com

“It’s all a lovely fairytale!” “O! the couple fit like a glove!”

“Well, its not long now, I hope, until their platinum day of love”

DAY 91

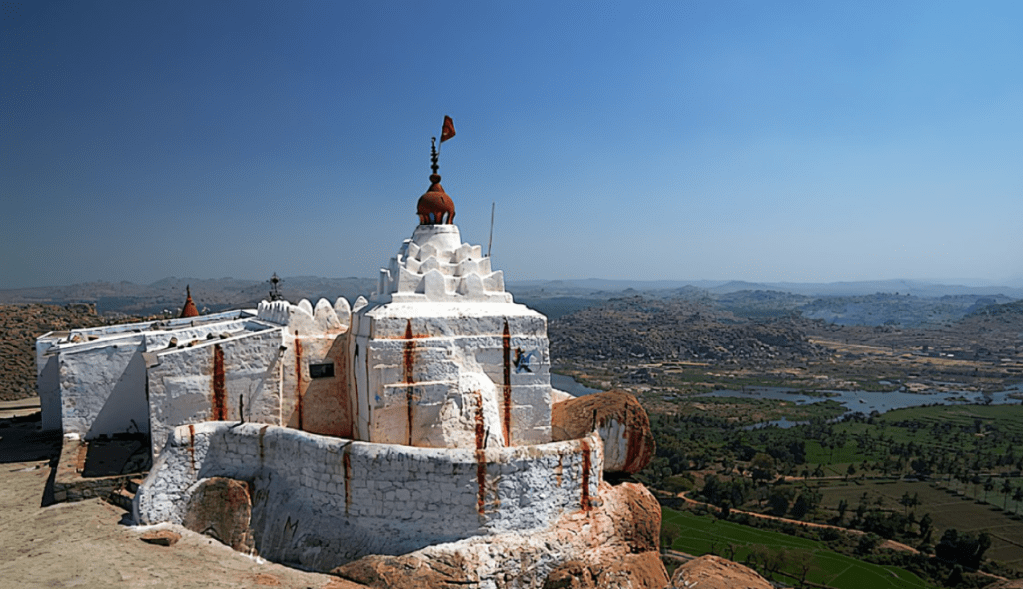

Jeypore town itself is not that big; its size & the way it peters out into the countryside reminds me of Wigton in Cumbria. However, what a countryside! On one side it’s a level plain stretching as far as the eye can see toward the state of Chittargarh. On the other is this wonderful horse-shoe of wooded hill, at the heart of which is this great hydro-electric dam. I took a walk over to it one day & came across this giant mace-wielding statue of the monkey god Hanuman, like a little slice of Disneyworld had been planted in India.

Back in Jeypore, one can find a shambling old palace in the centre of the town. You can’t get in, but can look down on it from neighbouring rooves like a sepoy sniper during the 1857 siege of Lucknow. There are also some proper filthy bits including this school whose playground is essentially a rubbish dump. Then there’s this old ghat, completely choked by weeds & rubbish. Still, I thought, I’ll take a wee walk round. En route I encountered 6 men having dumps, & had to avoid a thousand human faeces – not that nice an experience actually.

I met a really nice guy at the local internet shop, Niswa, whose name means world in the Oriyan language. We’d got on famously & he’d been playing me loads of Indian dance music, some of which I’m adding to my disco set. In return I gave him a load of western tunes, the like of which Jeypore has probably never seen. He says he’s gonna dish ‘em out to all his mates – so DJ Damo’s gonna be a big name in the Eastern Ghats, I hope.

He’s also invited me out for dinner tomorrow at a swanky local restaurant, which is really nice of the guy. Yeah, Jeypore’s great!

Adventures on an Indian Visa (week 12): Andaman Islands

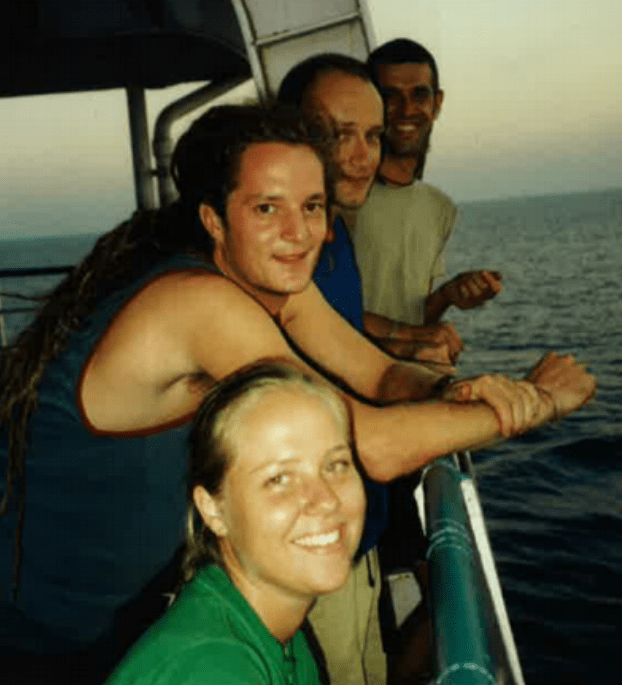

(Top to bottom): Kate, Phil, Steve, Duncan

DAY 78

The rickshaws in Chennai are the maddest I’ve came across. With the Andaman permit fresh in my hand & 50 mins til the boat left, I got this corrupt geezer who decided to drive me around Chennai with the meter on, clocking up a massive fare. Once I realised his game I scream’d at him, storm’d out in the middle of a busy main road & jump’d in an honest rickshaw. Of course , by the time I got to the port I disocver’d the boat was delay’d 5 hours – but of course this is India.

At the quay I met up with Steve, Kate, Jimmy Van de Mere & a couple of their mates call’d Duncan & Phil, the latter of whom had a bottle of liquid acid ready. Jimmy van de Mere had some ketamine bought cheap from a chemist in Gokarna en route, & I still had a bit of the opium left, an interesting ‘voyage’ felt on the cards.

So, towards the end of the afternoon we were in the bowels of the SS Akbar, a huge cavern of bunk-beds, all of whom are western tourists. We are apartheided from the Indians & we have a huge bunk class amidst the pipes that threaded thro’ the bowels of the ship. It is painted Kendal green & with all the ropes & rigging seems like a giant Jungle Jims. The other half of the ‘below ship’ bit is basically the same, but for Indians. Those with more money can take a cabin upstairs. It was cool, actually; lots of young, optimistic & excited travellers heading on a voyage of discovery, the spirit of which compell’d me to produce the following sonnet;

DEPARTING FOR ANDAMAN

Gazing across exotic ocean stream

Shamrock musing drifts to distant Burnley,

Where for as long as breathing there shall be

My family, my friends, my football team –

So far away, for following my dream

I am a stranger in a strange contree,

Though slowly hook’d upon its cup of tea,

Darjeeling serv’d up with a Devon cream.

The sun has fallen & the ship has sail’d,

The last lamps of the mainland shrink & fade,

A momentary notion has prevail’d,

Varuna on Makara far display’d;

Next time by solid ground my feet regaled

Into youth’s fleeting heart I shall have stray’d.

Day 79

My day on the boat started off mellow, reading in my hammock as it swung to the ships swaying, so I thought I’d try a bit of the opium again. Not long after I lick’d a drop of liquid acid from the top of Phil’s hand. I then had a jolly trippy time exploring my ship, the MV Akbar. The voyage was slowly turning into one massive mash-up as the only option from hanging out in the cramp’d & claustrophobic deck was getting wreck’d – a choice most people made. After sharing some opium with Jimmy Van de Mere, he whipt out a bottle of ketamine & cooked it up right there in the bunk. I tried a line & I had the most cosmic experience of my life really. I led back on my bunk & sort of sank into the universe – all I could see was an astral swath of stars, with a little chime of celestial music thrown into the mix. Then gaining some vague element of consciousness I lifted my body up & it was like breaking the surface of the sea, for suddenly I was surrounded by the blurr’d colours of the bunk class, but only for a few seconds as I suddenly reimmers’d myself in my opiod-ketamine-LSD ocean.

Eventually I came down enough to take charge of my faculties, & there follow’d a floaty few hours watching the ship scythe through the midnight sea. Being thrown into bunk class with another thirty Western tourists was cool, as I found a few new friends for the islands, which we’ll be arriving at in the morning.

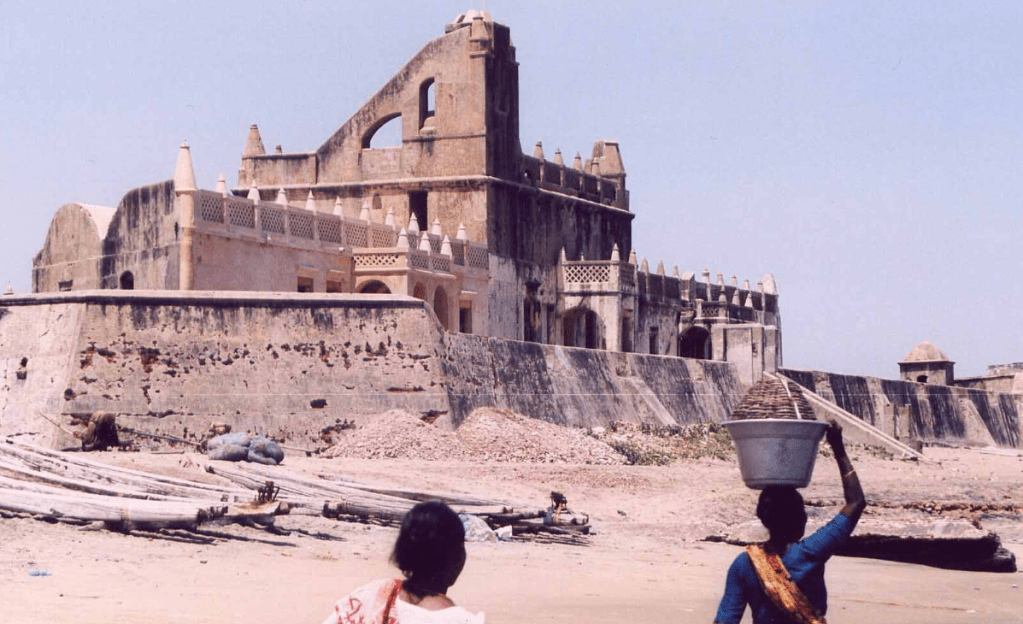

Day 80

This morning we pull’d into the Andaman capital, Port Blair, a sleepy little paradise with an old imperial residence swarming with banyan trees. The Andamans were once a post-1857 penal colony to deal with the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny, putting the ‘subversive’ anti-imperialists here rather like the Nazi’s Dachau, the French Devil’s Island & South Africa’s Robben Island. The Andamans are also like the English Channel Islands, being the only Indian ‘soil’ occupied by the Japanese during WW2, apart from a few cross-border excursions from Burma.

After a couple of hours pottering about the place – including an 8 egg omelette to counter the slops I’d been eating in Bunk Class -, a group of us (about 12 in total) bought some hammocks & then caught a boat to Havelock Island. I instantly hired a bike (my first one with gears) & razzed off round the island to Beach Seven (they don’t have names), making camp on the beach with Steve from England, a French guy & an Israeli lass, all in their early 20s.

The rest of the day was spent swimming, snorkeling, writing, & playing chess in the village with the locals. I’ve also found the next new Olympic sport… hermit races. Basically, you choose a hermit crab from the beach & place it in the centre of a circle drawn in the sand… first crab to the perimeter wins. We’ve also been cooking for ourselves & you will soon be able to taste the fruits of my newly acquired culinary skills – masalas & chapattis.

Then going to sleep above the scritches of en masse hermit crabs & the sounds of the Indian ocean, under a delectably bright balloon was beyond beautiful.

Day 81

My defining moment of the Andamans came this morning… Celia. She is a fine & feisty Norwegian Blonde, who while riding the rough track to the campsite I was struck by a fine ass, pass’d her, stopp’d & invited her for a spliff & a ride. So we took a tour of the island’s beaches, producing a moment to smile about til I die. On my left was the lumescent turquoise ocean, on my right the lush jungle, up above a perfect sun, down below a mighty motorbike, up in front the open road & right behind a gorgeous blonde. When spending a day at the office one likes to have pictures of sexy ladies to look at… I was sat writing my poetry while her skimpily clad curvature splash’d in the waves.

After dropping her off & getting back to the site, the police moved us on from our impromptu site this morning – no permits – so, I took a boat back to the capital where I had to soak my feet in Dettol water and cover them in plasters for frolicking among the coral has ripp’d them to shreds. You’ve gotta be real careful with your cuts, I’ve been told, as they can soon go bad in the humidity (and the fuckin flies know exactly where the sores are).

I am now in the wee townlet of Wandoor for a bit of solitude. My boat to Vizag leaves in two days, so I thought I’d have one last adventure before I leave – let’s hope it’s a good done !

Day 82

Fuck me! I have been genuinely unnerv’d, the closest I’ve come to death since a certain scampi pasta I cook’d up a couple of years back. This morning I bought a ticket for Jolly Buoy, a tiny island open to visitors for a few hours each day. We got there & sure enough it was paradise; jungle, white sands & shallow coral flush with lushly colour’d fish – thro’ my snorkel mask there appear’d an em’rald phantasie kingdom. So I had a couple of reefers & did a spot of writing whilst tucking into my pack’d lunch (major munchies) in a quiet, shady corner of the beach. After a while I went to check on when the boats would leave & to my horror found they had fuck’d off! I was completely alone on a deserted island with no sign of a boat anywhere – the boats might have come back in the morning, but after taking stock found I only had one third of a litre of water & half a samosa (vegetarian).

Across the waters fishing boats were hugging the mainland but they could not here my shouts over the sounds of the engines which chugg’d over the waves, then faded with the boats into the distance. So I was shipwrecked – & without a reality TV camera crew in sight! So, after stripping off naked I check’d out my possibilities. On one side of me was the ocean’s expanse (next stop Antarctica) & on the other, various islands of the archipelago. The closest one seem’d to be about a mile away, from where smoke seemed to be rising from the jungle… people! After two abortive attempts at swimming (not stoned enough) I tried to make a raft, which duly sank. Fish kept flying out of the water reminding me I was in tropical waters & I remember’d that someone had seen a four foot shark two days ago not far from here. After another spliff I thought fuck it, it’ll be an adventure & began to swim.

After 15 minutes of easy breaststroke I look’d back & realised the current was sweeping me out to sea! Panic kick’d in & I turn’d round for Jolly Buoy, but the current was really strong. For the first time in my life I was dependent on my own strength to save my skin. I swam & swam & swam, my life flashing before my eyes – nor more peachy lady bottoms, no more Yips Chips, no more black pudding from Burnley market, no more of my Gran’s Lancashire hotpot. Fuck, Gran, she’d fuckin’ kill me if I hadn’t just died in a rip-tide in the Indian Ocean.! Fortunately, after a full-on heave of effort my feet touch’d solid & I collapsed in the sand, listening to my thumping heartbeat in a state of shock…

thump…. thump… thump… thump… thump… thump…thump…chug….chug…chug-chug-chug…

Another fisherboat!

This time I shouted as loud as I could & waved frantically & almost piss’d myself when I saw them turn for the island. I quickly dress’d & greeted them passionately – they were very curious about me – & soon we were chugging out across the waters. I quickly skinn’d up & pass’d a spliff round my three new shipmates & lay back in the boat to watch the magnificent sunset – a sunset I was lucky to see! They also gave me a top tip – if u are ever stuck on a desert island you must wave a piece of material to signify you have been stranded (internationally understood).

At the astonished fisherman’s village I gave a geezer 60 rupees to drive me on the back of his bike to my hotel – about 30 miles all in all – where I order’d a huge feast. Like loads of fucking food, most of the dishes on the menu.

After telling my tale to my hotelier, he said apparently I was lucky not to have reach’d the island I was swimming to (with the smoke curls), as there was a good chance they might have in fact eaten me! It certainly seems that Sarsawathi has smil’d on my life today, & I’m not being allow’’d to leave this mortal coil this yet – more work to do, perhaps!

Day 83

A guy from the Forestry commission came to see me this morning & they will be taking action against the boat owner, despite my protestations as to the otherwise. I figured if their chief witness (me) had fuck’d off the captain couldn’t get into trouble & would be able to continue feeding his family, so I scarper’d back to the capital as soon as they left, penning the following sonnet;

Down southern Andaman lies Jolly Bouy,

Of rainbow coral, full of snorkling joy,

I spent an hour lagooning in a laze,

& fell astoned, then woke, to my amaze

The boat had left me, deserted, alone,

No rizlas, samosas, water, nor phone!

A mile or so across the sharky foam,

A trail of smoke show’d someone was at home,

I built a brushweed raft, but that soon sank,

So off I swam, my goddess I should thank

For showing me this was a wild riptide,

Young muscles haul’d me back, I’d nearly died!

Then, waving to distant boats, at sunset,

I’d be the strangest fish they’ve ever net.

With a few hours to kill before my boat, I potter’d about Port Blair again, completely reliev’d to be alive. I went to check out the Cellular Jail, the main hub of British oppression to where the naughtiest members of the Indian Independence movement were sent. Known as Kālā Pānī (‘Black Water’), the term actually means an overseas journey which strips someone of their caste, leading to social exclusion. Far from the parlour rooms of mercantile London, the full evil of British imperialism was showing its face, with an eventual 80,000 political prisoners facing “torture, medical tests, forced labor and for many, death.” (Guardian Sat 23 Jun 2001). Here’s a quote from that article;

“We are forgotten victims,” says Dhirendra. “Back then, all we wanted was food, and you gave us gruel that was riddled with white threads of worms. We demanded an end to work gangs, and we ended up chained like bullocks to oil mills, grinding mustard seed, around and around. We wanted medical aid for our fevers, and your doctors signed papers stating we were fit enough to flog Dhirendra Chowdhury

Towards dusk I boarded my ship to Vizag & away we went once more. Unfortunately I soon began to feel very sick indeed with some kind dysentry (have you ever shit blood?). Along with an Amsterdam whore I think a young man’s first tropical disease is an initiation into manhood – my body can do that!? The worst moment came when I was flopped on a crusted over ships toilets, sat down where one usually squats & to week to stand, with the ship’s rats scuttling about & my whole body liquifying & gushing out of me – & this only 36 hours after nearly drowning in shark infested seas !

Day 84

I stagger’d to the ship’s doctor this morning, who gave me some pills & before you know it I was feeling at least half better. So, I decided to finish off my opium, & read a book in my bunk. It’s call’d Life of Pi, a vivid, wonder-suffus’d Booker Prize winner by Yann Martel. Its a story about this shipwreck where this guys changes his fellow shipwreckees into animals – an orangutan, a zebra, a hyena, and a Bengal tiger – just to stay sane. In the book there’s this one amazing section which can describe Hindu in a way that I could never;

I am a Hindu because of sculptur’d cones of red kumkum powder & baskets of yellow turmeric nuggets, because of garlands of flowers & pieces of broken coconut, because of the clanging of bells to announce one’s arrival to God, because of the whine if the reedy nadaswaram & the beating of drums, because of the patter of bare feet against stone floors down dark corridors pierced by shafts of sunlight, because of the fragrance of incense, because of flames of arati lamps circling in the darkness, because of bhajans being sweetly sung, because of elephants standing around to bless, because of colourful murals telling colourful stories, because of foreheads carrying, variously signified, the same word – faith, I became loyal to these sense impressions even before I knew what they meant or what they were for. It is my heart that commands me so. I feel at home in a Hindu temple. I am aware of Presence, not personal the way we usually fell presence, but something larger. My heart skips a beat when I Catch sight of the murti, of God Residing, in the inner sanctum of a temple. Truly I am in a sacred cosmic womb, a place where everything is born, & it is my sweet luck to behold its living core.

After a lazy day sailing, in the dark of night, on first seeing the shore lights of the subcontinent, I penn’d the following sonnet’

At the back of the ship, at the height of the trip,

Drawn by the harmonies of Lord Vishnu’s call,

Navel-rooted lotus soft floats over waters

Absorbing the beauteous Bay of Bengal,

Transcending to milk, pearly seaway of silk,

Thou lavender cushion of infinite white,

Surrounding the foetal spirit centripetal

Sucking upon toenails painted starry bright.

“Rider, thou art return’d to India,

Saraswathi, I see, has smil’d on you,

Thy mortal aura bless’d in her prayer,

Thine energies hued in a rainstorm blue,

Come drape thyself in the Himalaya,

For there, thy Rose of Sylver shall renew.”

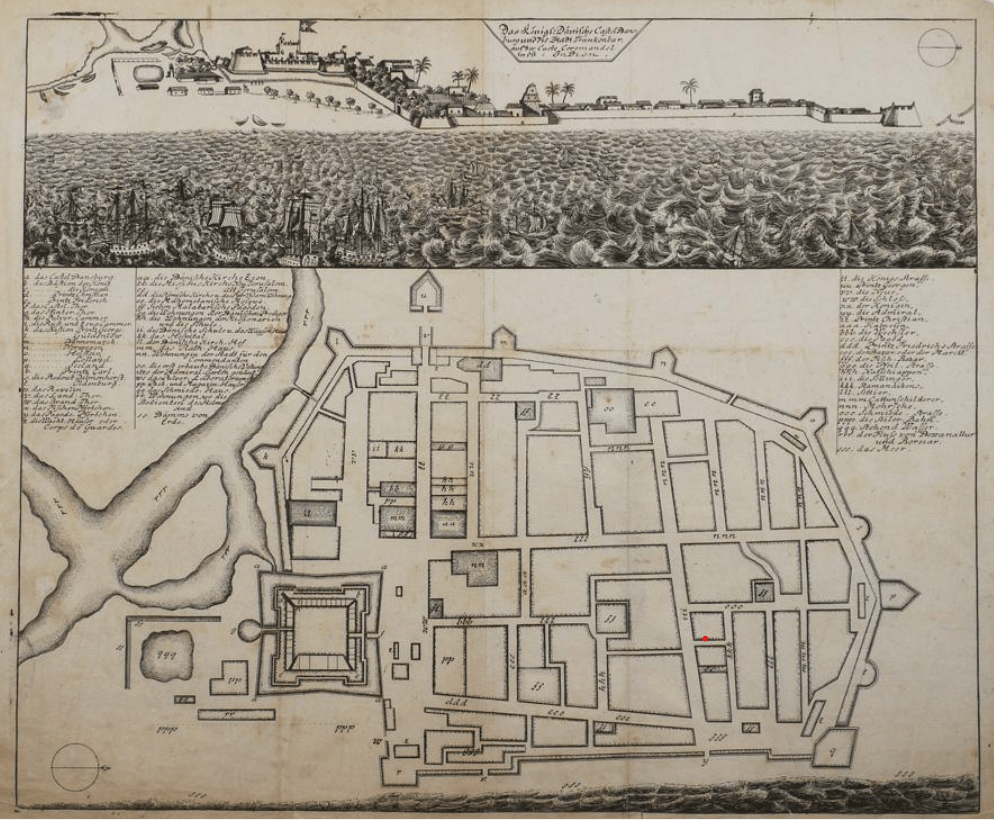

It was cool sailing into Visakhapatnam as it’s port is pretty ancient, being the only natural harbour on the east coast of India. The Romans were here, for example, & now an English poet was taking his first steps in the state of Andhra Pradesh via its funky harbour. Thus, I am now in ‘Vizag,’ the so called ‘City of Destiny.’ It’s nothing special so far – but I’ve only seen the port, a few streets & my hotel. I do have the feeling, however, that it’s gonna be a great place to hole up & explore for a couple of days!

Adventures on an Indian Visa (week 11): Charlie Chennai

Day 71

This morning a took the chunk-a-long, but wonderful train back down to Coimbatore, which was soon follow’d by a pretty hot & tedious train journey to Chennai. It was all a bit wild & busy when I got there, & I just jumped in a rickshaw, said take me to a hotel & pretty much took the first decent looking one & had a quiet night. Charlie gets here tomorrow night, tho, which will be funny. The most significant event in my Indian education concerning my musing upon the land’s weird-to-me body language. A shake of the head means yes; when a rickshaw driver pulls up next to you & I say what I think is no, they take it as yes & follow me down the road until I’m forced to tell him to fuck off. In the West we turn the palm face down for a shoo-off gesture & face up for a come here. Well, our shoo-off is the Indian come here, so when I find myself with several waiters watching me eat, & tell them to shoo-of, they actually come closer. Trust me, it’s mad as fuck having your every spoonful scrutinized by up to 20 sets of eyes.

Day 72

Waking up in Chennai with a few hours to kill before the arrival of Charlie would completely disturb my erudite fen shui, I spent the late morning & afternoon at Madras University & its Marina Campus Library. It is situated right by the stretching golden sands of Chennai Beach, framed by the choppy waters of the Bay of Bengal.

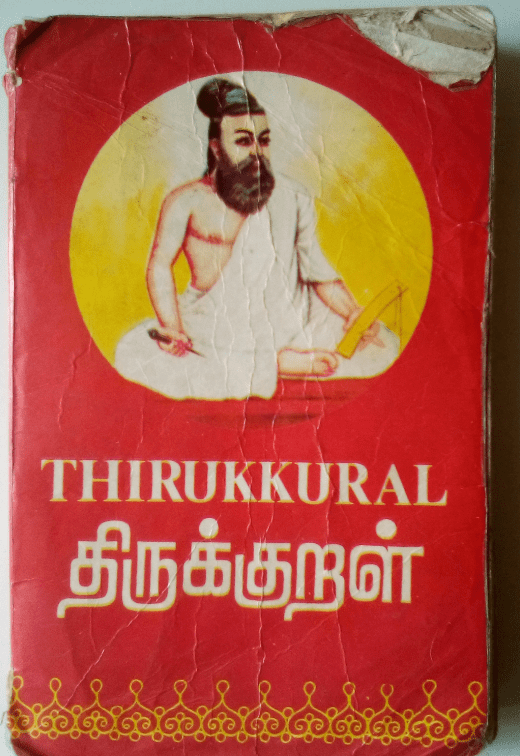

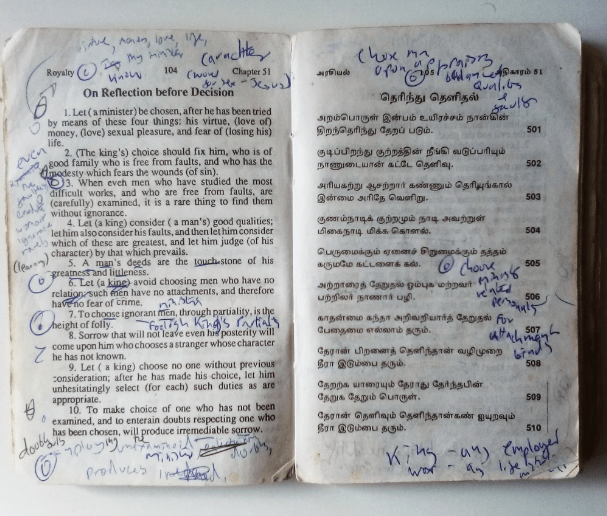

While on a wee break & wandering around the Ancient Indian History & Archeology Department of the Madras University, by some crazy chance I met a professor who, to cut a long story short, is up for teaming up with me to produce a new rendition of Tirukural, translating the introduction I composed into various Indian languages – an interesting project & one he says was sent to him by god. He even said I was an Indian in one of my previous lives, which kinda makes sense, & made me pray along to the Vedas with him, which I did awkwardly but silently…

What a contrast, then, when I met Charlie at the airport, clucking on cold turkey off practically every kind of drug, knocking back Valium like sarsaparilla tablets, wash’d down with neat vodka & immediately demanding we go searching for some crack. I soon discover’d the source of his hedonism. Apart from being on the run from the police, his landlord, the CSA & a couple of crack heads, he’s also nursing a broken heart. She was called Ketamine Karen, & had bled him dry, emotionally & financially, & turned him onto smack etc. However, I know the guy’s got a diamond soul, it’s just been buried in a whole heap of shit, so what’s a pal gotta do eh?

So, instead of paying the exorbitant taxi fares into town like an American mug full of dollars, we just caught a train instead, the station being a stone’s throw from the airport. Our tickets were 6 rupees each, about 8p & we were on the train with the vallies kicking in & Charlie staggering about & landing on this woman’s lap & here husband wanting to throw him off the train. I somehow managed to diffuse the situation & get him back to the hotel room, which Charlie said was the worst he’d ever been in. Trust me there’s worse – at least we have a western toilet, shower & TV (for a fiver). Admittedly, the area we are in is right next to a very busy, smoggy main road, & Charlie says its like holidaying in Wolverhampton. Anyway, the vallies soon did their magic & sent him off to sleep, which finally had a respite from Charlie’s tales of Great Harwood Football Club.

Fer fucks sake, I’d forgotten how badly he snores!

Day 73

Charlie was far too jet-lagg’d/vallied-up/clucking for crack to spend any time with today, so while he dozed about the hotel drinking cheap rum, I headed out into Chennai, the capital of Tamil Nadu. The city itself is just one massive heap of concrete lumped on the Tamil plain like a colourful pizza. No hills to break up the urban monotony, & very few parks. Albeit there’s the sea, but even this is manky, fed by the black stinking sewers & even ranker rivers that flow through the city. Still, for my studies it provided a double whammy, for according to popular tradition, one of the city’s suburbs – Mylapore – saw the martydom of St Thomas. How he got there goes like this;

Where the Didascalia (dating from the end of the 3rd century) states, ‘India… received the apostolic ordinances from Judas Thomas, who was a guide and ruler in the church which he built,’ elsewhere, the 7th century patriarch of Jerusalem, Sophronius, records that Thomas preach’d; ‘the gospel of the Lord to the Parthians, Medes, Persians, Carmanians, Hyrcanians, Bactrians, and the Magi. He fell asleep in the city of Calamina of India.’ Calamina is derived from Cholamandalam, which means ‘Realm of the Cholas,’ the rulers of ancient Tamil Nadu. Elsewhere, the apocryphal Acts of Thomas describe his death, burial, & subsequent disappearance of his remains;

And when he had thus prayed he said unto the soldiers: Come hither and accomplish the commandments of him that sent you. And the four came and pierced him with their spears, and he fell down and died. And all the brethren wept; and they brought beautiful robes and much and fair linen, and buried him in a royal sepulchre wherein the former (first) kings were laid.

Now it came to pass after a long time that one of the children of Misdaeus the king was smitten by a devil, and no man could cure him, for the devil was exceeding fierce. And Misdaeus the king took thought and sad: I will go and open the sepulchre, and take a bone of the apostle of God and hang it upon my son and he shall be healed… And he went and opened the sepulchre, but found not the apostle there, for one of the brethren had stolen him away and taken him unto Mesopotamia

For Mesopotamia read Syria, where a certain Ephrem writes in the forty-second of his ‘Carmina Nisibina’ that Thomas was put to death in India, and that his remains were eventually buried in Edessa, Syria.

It was to a land of dark people he was sent, to clothe them by Baptism in white robes. His grateful dawn dispelled India’s painful darkness. It was his mission to espouse India to the One-Begotten. The merchant is blessed for having so great a treasure. Edessa thus became the blessed city by possessing the greatest pearl India could yield. Hymns of Saint Ephrem

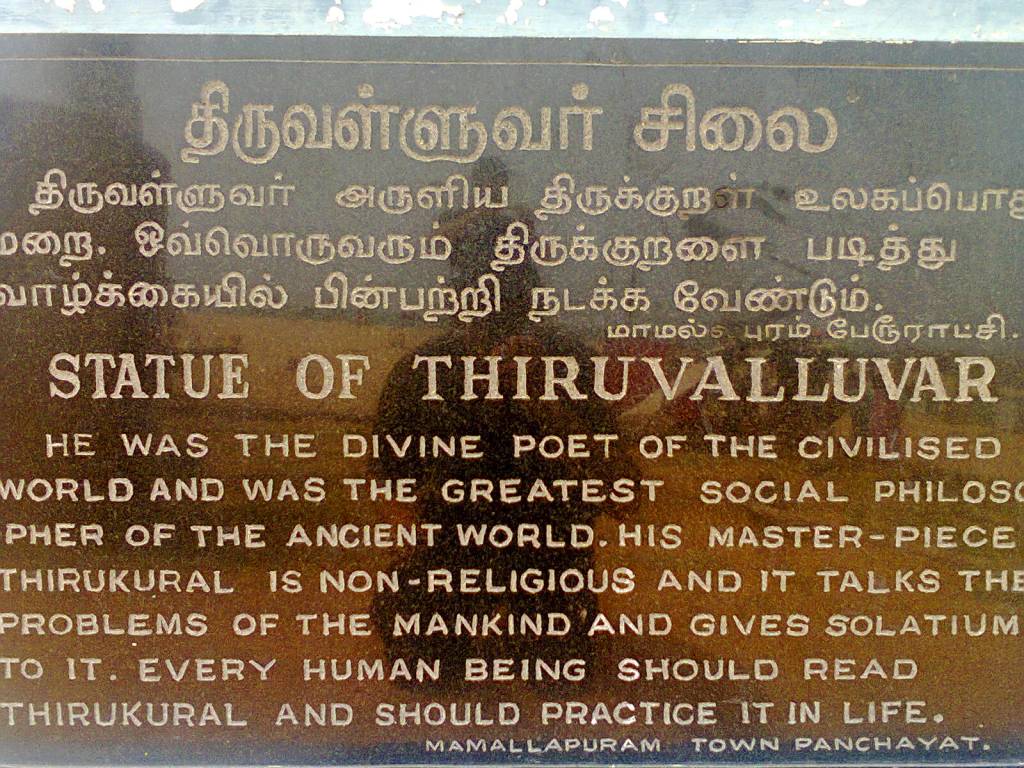

So much for Saint Thomas. Now the site of his passing, Mylapore, is absolutely fascinating, for it was also the reputed birthplace of Thiruvalluvar himself. My Thiruvalluvar. Now, there’s no such thing as coincidence, the Universal mind doesn’t allow it, so deep down inside my instinctual subconscious I’m like, what is the real connection between Thiruvalluvar & St Thomas, & swore a silent academic oath to find it, especially when one of the first western scholars to describe the poetical wisdom contained in the Kural was RT Temple, who declared it to be;

One of the grandest productions of man’s brain, much of which bears so strange a resemblance in thought to the Sermon on the Mount. It has accordingly been argued ere this, with much show of probability that the teachings of the gospel influenced the nameless weaver of Mayilapur

My rickshaw took me to Mylapore – a quiet enough spot on a hill overlooking the sea, with a monument upon the very spot where Thomas was purportedly slain. Mylapore was also the location in which Saint Thomas erected a church upon an ancient Hindu site called Kapaleeswara. ‘The first Portuguese historians,’ recorded Father Henry Hosten, ‘say that St. Thomas built his ‘house,’ meaning his church, on the site where a Jogi had his temple.’ It is even possible that Hosten’s ‘Jogi’ was Thurivalluvar himself! The idea that one influenced the other leads to an assemblage of sayings known as the Gospel of Thomas. Discovered near Nag Hammadi, Egypt, in only in 1945, this obscure Gospel is actually just a Kuralesque, nuggets-of-wisdom collection of 114 brief & wise sayings of Jesus made by a certain ‘Didymus Thomas.’

Jesus said, “He who will drink from my mouth will become like me. I myself shall become he, and the things that are hidden will be revealed to him.” (Gospel of Thomas)

Around pleasant, intelligent speakers / People swiftly gather (Thirukural)

Jesus said, “Whoever finds the world and becomes rich. Let him renounce the world.” (Gospel of Thomas)

Prefer destitution’s stark minimalism / Possessions befuddle mind (Thirukural)

Jesus said, “Fortunate is the man who knows where the brigands will enter, so that he may get up, muster his domain, and arm himself before they invade.” (Gospel of Thomas)

Adherence of wise counsel / Frightens our enemies (Thirukural)

On returning to the hotel, Charlie was now wide awake & up for an explore. So, we went for a walk which basically entail’d Charlie having a wee moan about everything from lack of non-sugary condensed milk to the bricklaying skills of the Indians (he’s a brickie himself). While we were struttin’ the streets, me & Charlie kicked off our own version of the East Lancashire cricket league. Apparently, & quite the sportsmen, he played for Read CC, while I used to watch Lowerhouse CC as a bairn. Anyhow, on coming across a couple of kids playing in the streets, we found ourselves using a tree for a wicket, & the kids for fielders. Charlie batted first & got 7 runs before I bowl’d him plumb LBW, much to his cocksure annoyance. However, I only made 5 runs before one of the kids gave me a wicked googly & Charlie gave rather a too triumphant cheer. His smile didn’t last long though – later that night he got himself lost. I think he went off hunting for ketamine while I was in the internet shop studying Saint Thomas in India. An hour after our appointed rendezvous I gave up waiting & went back to the hotel, where three hours later a rather fluster’d Charlie turns up, without any K (thank god), & several hundred rupees of taxi fares down. Apparently he’d driven past the hotel several times – funny as.

It was the perfect time to tell him I was taking him to an Ashram to sort his life out. I don’t think he quite heard, or perhaps understood. This is gonna be funny.

Day 74

This morning we woke to proper Pendle weather, with Chennai like a late autumnal Manchester. Apparently a cyclone is coming in from the Bay of Bengal to devastate fisherman’s lives & all that – which finally gave us the kick up the ass we needed to get out of Dodge. Three hours of train ride later, sitting in front of a baby with massive brown eyes & an even bigger brown splodge of paint between them, held by a guy listening to bangra on his mobile, we came to Tirupathi, a not particularly pleasing town at the foot of a sheer range of hills. If Chennai was Wolverhampton, said Charlie, this is definitely West Bromwich.

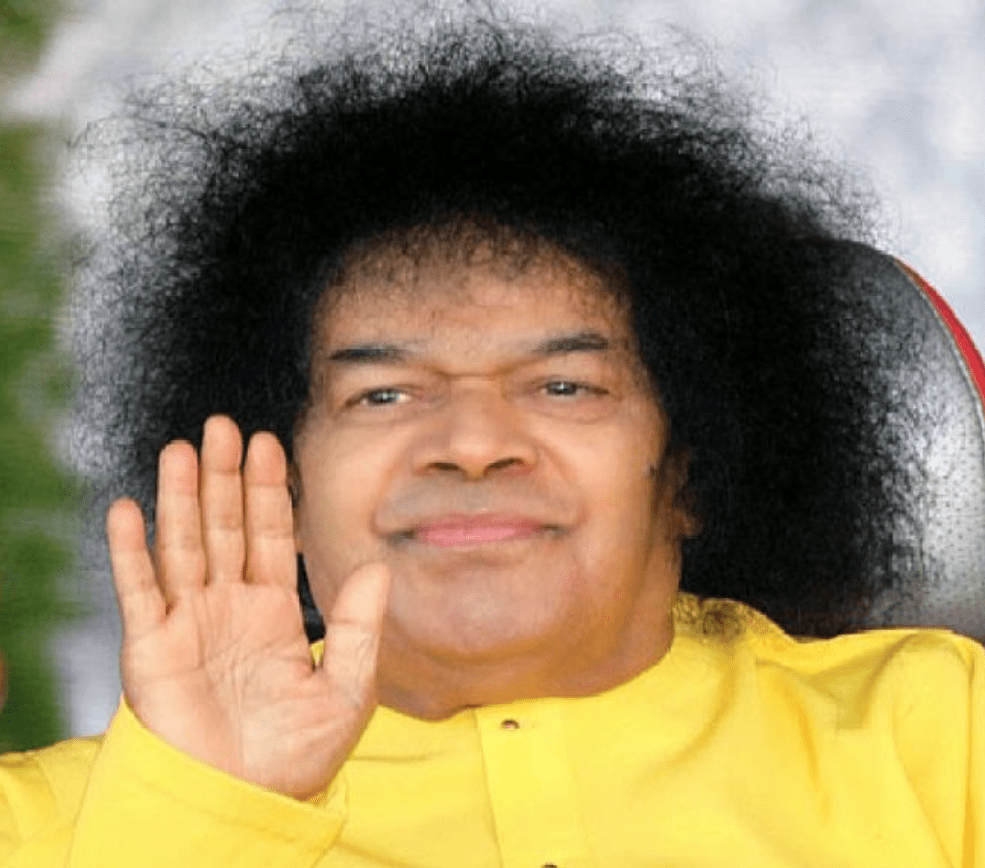

Our reason for being there was the temple of Tirumala, up on the hill range. It receives more pilgrims each year than Mecca & Rome put together, with most of the young guys shaving their heads – giving the appearance of a mass rally of the Asian wing of the BNP. We’re gonna join ‘em about dawn tomorrow, when hopefully the weather would have cleared, before travelling a few hundred K to stay a night at this very holy ashram – I can’t wait to see Charlie’s face when we get there & he can’t have a fag.

Day 75

Our journey to the ashram began with me attempting to invoke Charlie’s spirituality. We got up early, at 5.30 AM, to try & squeeze in a visit to the world’s most visited temple at Tirumala. Unfortunately, during the night both me & Charlie got a bout of Delhi Belly, & ten minutes into a bumpy ride decided it would be best if we get off & find some bushes, pronto. We did, call’d off the trip to the temple for fear of lack of bushes, & walked back into town, picking up some ‘stabilising’ medicine en route. At 9.30 am we caught the bus west. This was a nine-hour journey across the otherworldy landscape of the Deccan plateaux. It is basically a vast plain, peppered with bouldery hills, whose rocks seem to defy gravity as they balance at strange angles. The journey was broken up by the occasional crazy town & the growing feeling I was yet again in ‘endless India.’ I mean, we travelled about 350 k today, & hardly made a dent on the subcontinental map.

We then hit Puttupathy, passing the Sri Sathya Sai Super Speciality Hospital as we went in – a gorgeous pink Taj Mahal of a thing. We soon found ourselves in Sai Baba’s ashram called the Prasantha Nilayam, or hill of peace. On the way in there was a security check, & they took Charlie’s fags off him which really upset him, it was hilarious. On the brighter side, we got a bed in a dormitory full of international devotees for only 20 rupees – about 25p. The food was just as cheap, & we finally had a few western birds to check out. There was obviously no chance of getting laid, like, especially with a still brooding Charlie in tow. Outside the ashram we found your typical traveler-world – loads of shops selling jewellery, clothes & sitars, mingling with internet joints, hotels & restaurants, between which roam’d posses of beggars. It is a weird contrast – on one side of the street there’s this big meditation centre, & on the other a great cathedral to capitalism. If you ask me, Sai Baba’s raking it in like a modern-day Idi Amin. We even passed his private air strip as we arrived. Plus, as we ate our food in one of the several halls, this sign looked over us with just his hypnotic eyes staring down, reading;

WHY FEAR

WHEN I AM HERE

Trippy shit – there was also this board, which read;

Camera / Video Camera / Calculator

Big Bag / Battery / Binocular

Tobacco / Time piece / Toffeebags / Umbrella

Mobile / Plate / Time Piece / Needles

Blades / Water Bottle /Eatables

Scissors / Cassettes / CDs / Calculator

Knife / Book / Lighter / Cigarettes/ Pen

Flowers /Footwear / Flashlight / Walkman

MATERIALS NOT ALLOWED DURING DARSHAN

The whole ashram reminds me of a holiday rehab camp – there’s loads of accommodation – the westerners get bunk beds while the Indians sleep on mats on the hard floor. The night’s sleep reminded me to get some earplugs – Charlie’s bad enough, but nothing to the Russians. I kept moving about the dorm from bed-to-bed avoiding a snorer, but as soon as I’d settled, the guy next to me would start – proper did mi head in. In the end I got an hour’s kip, & with Charlie’s arms bitten to a volcano range by the local mozzys, we left the ashram, passing a mini-darshan on the way. This took place in a great ballroom style area, with chandeliers draping down & a couple of hundred white-clothed devotees sat on a polished silver floor, singing along to this guy at the front chatting through a PA. While I observ’d all this, I penn’d the following sonnet;

AUM SRI SAIRAM

Indian & international descends on Puttupathi,

Form the swarming cult of the new Sai Baba swami,

A mark’d contrast to the monstrosity park’d outside,

That cathedral of consumerism, devotion’s grotesque bride,

But safe behind those guarded gates one meditates quite freely

& joins in Dharsan with, oft-times, Sai Baba, tho’ him eighty,

Being the second avatar of a word-wide, tutelary spirit,

That three times only this green planet will grace with a visit;

Upon his death the first foresaw his rebirth after eight years

In obscure Puttupathi, where many years after the prophecy,

The teenager toss’d flour on the floor in the middle of a thrashing,

Spelling out Satay Sai Baba – the boy had always been holy,

& soon the world’s second largest NGO, after the UN of course,

Springs up, a shaft of light providing free health care for all.

Day 76

This morning I said my goodbyes to Charlie & agreed to meet him in a few weeks somewhere near Calcutta. I’m gonna sail back from the Andaman islands via Visakapatnam & head north thro Orissa. He’s fine with it, he knows he needs it & this morning I already noticed a wee change in his demeanour & aura, but he still kept nipping outside the ashram for fahs & a cheeky rum.

While waiting for my train back to Chennai, a very funny few hours began. There was this cute Israeli girl – a 24-year-old called Gal – who I approach’d, as one normally does when surrounded by Indians in a case of ‘I’ll watch your bag if you watch mine.’ I said I’d also ‘protect’ her from any cheezy sleezy men. Anyhow, something happened on that train, a wee spot of Cupid I think, & found her gazing at me with these big, brown, dreamy eyes. The Indians around us thought us man & wife & after a while it actually felt like we were. Changing trains, we were stood on the bridge over the platforms, the sun just setting, & making out like crazy.

Sensual spontaneity at its most romantic, yet I felt a wee bit hypocritical as her protector had ended up hitting on her. We had two more hours together. My train was heading east & hers was heading south. Unfortunately, the railway retiring rooms were closed (we were both up for it) so we just found a bench on a quiet platform & hung out. She was a great kisser by the way.

After one last snog to the sound of engines & cacophonic tooting I left Gal & I got on the Chennai train. There was plenty of food being touted up & down the aisles, from ice cream & samosas, to full meals & packets of sweet cherries, with the beggars not far behind; the blind, the limbless & the decrepit. There were also two ladyboys who did their weekly ‘shopping.’ They turn up with an aggressive hand clap & basically demand money off the men – which they invariably get. Apparently they are only allowed to do it on Fridays & Saturdays – something for the weekend I dare say.

I finally return’d the vast Westernesque sprawl of Chennai (Madras) where tomorrow I intend to get a permit for a visit to the paradisial Andaman Islands. Steve, Kate & Jimmy are due in as well, so it’ll be quite the reunion, one expects. I’m looking forwards to it very much.

Day 77

Spent today sorting out my permit to visit the Andamans. I hired a rickshaw for the day & had an idea of buying a fleet of rickshaws & build track at home so we can all play Rickshaw Races – with a couple of guys hanging out of the windows with baseball bats! For a cheaper price for hiring my drivers, we rocketed around on loads of crazy missions – they get paid for taking westerners into luxury shops -, including a trip to his weed-dealing cousins, the overall net result of which was I get my permit tomorrow morning at 9 AM & there’s no actual guarantee of gettin’ on the ship. Fortunately there’s about twenty others in the same boat (pun intended), including the Goa gang, & we’re all gonna go down en masse waving 500 rupee notes & smilin’ widely. If they don’t let us on, we’re gonna sink the bastard!

Adventures on an Indian Visa (week 10): Hill Stations

Day 64

After completing the pen & paper version of the Thirukural, I printed out the first draft of my transcreation this morning, & was looking forward to a leisurely editing process, printing it out, drinking a few beers over a few plates of tasty food, scribbling away in a poetic half-dream. Of course I was wrong, this is India, too many variables, too many chances to progress on a plan. It begins with my new-found love for a possible new-found vocation of being a ‘literary archaeologist’, to whom the libraries of exotic countries are like the mausoleums of antique emperors, the treasures of which have lain undiscover’d under centuries of dust… & so to the central library at Madurai. I’d decided to spend a few hours there, unwinding & studying a few Tamil poetic measures, when I stumbled across the Nalatiyar. Well, less stumbl’d, more guided there by the statue of Thiruvallavar downstairs. It turns out that this collection of 400 quatrains is actually the revered sister-poem of the Kural, tho’ nowhere near as famous. There is an old Tamil proverb praising which says;

The Nalatiyar and the Thirukural are very good in expressing human thoughts just as the twigs of the banyan and the acacia trees are good in maintaining the teeth

I felt a bit like Howard Carter as he found a new door in the antechamber of what he thought had been the main royal tomb in 1922. Beyond that door lay Tutankhamun. “Great,” I thought, “a good reason to come back to Tamil Nadu… wait a minute, fer fucks sake I’m here already!”

I decided there & then to ‘have a pop’ at it’s transcreation, shov’d the book up my shirt & left the library with my now stolen copy of the Nalatiyar. Life’s all about taking risks sometime, & this wee crime was something I just had to do. The Nalatiyar’s form is actually in quatrains, not the couplets of the Kural, but what I’m gonna do is find the main spirit of each quatrain & kuralize them. So tomorrow I leave the scene of the crime & head for the hills, where Kodaikanal sounds like a much more salubrious location to compose. It’s supposed to be a very gorgeous hill-station, with lakes & trees & shit, so happy days.

Day 65

This morning I printed out my version of the Kural at a nearby printers a shack – a rupee per sheet -, & as I flick’d through them walking back to my pad I felt like Thiruvallavar would have felt as he carried his palm leaf manuscript about the streets of Tamil Nadu 2000 years ago. It was now time to check out, but before I did I thought I’d get one of the hotel’s advertis’d continental breakfasts. It was basically a jam butty & a cup of coffee & after a lengthy parting argument with the owner he’s agreed to change the menu heading to ‘sub-continental breakfast.’ At the bus stand I topp’d up on poori instead & hopp’d on a bus to Kodaikanal, a journey which swept me plain-to-plain over the Palani Hills – a mountain spur that juts out easterly from the main chain of the western Ghats.

The final stages of my journey to Kodiakanal here were ones for the soul, my bus sluggishly climbing the winding mountain roads for a good 50 kilometres. At every turn the scenery was wonderful, from mile-high waterfalls to the glittering lakes in the plains far below. The lush greenery was pepper’d with purple, pink & orange flowers, & the landscape seem’d very much like that of the Pyrenees. As India once more alter’d breathlessly its natural prospect, I recognised how much of a global microcosm this single nation is.

So, at the top of the Palani Hills, which at 2000 meters above sea level are twice as big as Ben Nevis, lies Kodaikanal, & I was rather surpris’d to discover how sprawl’d-out the busy, ‘taxi-taxi-taxi’ town was. With houses hugging the slopes all around the central lake, I felt like I was in Rome or Sheffield, only up high in the heavens as the plains below us were obscur’d by a pure white sea of cloud, shining brilliantly under an unadulterated sun.

I spent the day pottering about & working on the Naltiyar & the printed Kural, & found that whereas by day, Kodaikanal is a pleasant 20 or so degrees, by night & the temperature drops to about 10 & I found myself practically freezing to death, & so rush’d to my bed & the epic blankets the hotel provided. It made me realise I will definitely need some warmer clothing if ever I get to the Himalayas.

Day 66

This morning I woke up with what turned out to be a wee spot of flu. After spending a couple of hours in bed with a fever & convinced I was dying of some kind of fatal mosquito-borne disease, I explain’d my symptoms to a pharmacist & a few pills later & I was feeling better. But not wanting another chilly night to aggravate things, I decided to seek instead the invisible duvet that is lowland India & descend once more to the heat of the plains.

The journey to Palani was among the greatest I have ever taken. The mountains were simply gorgeous, a kind of snowless New Zealand, lush with the greenery of an English country forest. Half-way down the serpentine roads we even stopped for tea at a lovely spot, perch’d high over the plains. Below me, by a glittering lake, was the temple town of Palani. We reach’d there after a pleasant descent, the green sea of coconut groves growing ever nearer, until with a metaphorical splash those treetops were now above my head.

I had a bit of time before my next bus, so I took a wee trip to a temple, perch’d atop a little hill, with the mountains I had recently left behind towering magnificently over the scene. It was totally rammers inside, with the rattle of toy plastic guns going off every few feet. The vibes weren’t for me, so I took a walk around a bit of the lake instead – where I got my feet mucky as fuck. There then followed an amusing moment when I thrust myself among some women filling up their water carriers, asked to use the tap, & got my feet & sandals cleaned by a not unattractive bird.

My next bus took me to the city of Coimbatore, the supposed Manchester of India. I have to disagree, tho’, for everyone here has a charming, accent, pleasing & amiable manner, plus the sun shines all the time – & I haven’t even heard Fools Gold once. At first I thought that I had another Ramashwaram on my hands – its still holiday time & every lodge was filled up. Luckily, I manag’d to get a room in a pretty decent hotel just towards the end of a long semi-fluey day – but I’m still alive & I’m still working on my poetry! This evening was the one in my life where I was transcreating the Nalatiyar in Coimbatore. It just sounds fuckin’ cool, dunnit!

Day 67

Felt much better this morning & hit the Indian morning rushathon with a smile. My hotel’s quite central & I felt like someone who lives in Soho stepping out into Tottenham Court Road. I’m totally in my element here, an anonymous being roaming among this seething mass of humanity. Back in Britain I kinda dawdle about on the outside of society as a poet – I don’t even do performance poetry, & I’m too epic for the publishers, so I’m pretty much on my own. Out here things, tho’, things feel very different, I feel a part of the eternal, international poetic consciousness – with the added bonus of watching live premiership footy in my hotel room!

Coimbatore is also hosting this trade fair at the moment, & I went down to check it out. I was a little disappointed at first, until I was told I’d gone into the children’s’ playground next door by mistake. But I did see some kids playing kabbadi on rollerskates – very cool. Next door was the trade fair; one big, happy Tamil family full of stalls which in the main were as tacky as Burnley’s indoor market. There was a wicked fair, though, whose rides; from ferris wheel to crazy spinny things, would put many in Britain to shame… but after the waltzers on Brighton pier back in 2001 I’d sworn I’d never get on another fairground ride & stick firmly to my vow. However, I’ve never said anything about camel rides, & after watching groups of up to 4 parents & kids float about these ships of the desert, I thought ‘fuck it,’ paid 40 rupees so I could have the thing to myself, & went bobbing about the fair, the only adult on a camel, much to everyone’s amusement.

Got an email from Kate, my pal from Goa. Apparently, she & Steve, along with Jimmy Van de Mere & a few others, are all heading to the Andaman Islands & will be in Chennai soon. I’ve googl’d them & they look fantastic. To get there you have to cross the Bay of Bengal on a big ship, so that’s also cool. The problem is Charlie. He really does get on peoples’ tits, I can handle him, but so many times I’ve heard – ‘is Charlie your mate, Damo?’ & I’m like ‘yeah,’ then they say quite curtly, ‘why?’ So I’ve hatch’d a plan – Charlie definitely needs rehab, so a stint in an ashram will definitely help, so I’m gonna google some near Chennai, drop him off at one, then fuck off to the Andamans for a week or two, before heading back to Chennai & hitting the road with him. Tho’ its also possible to sail to Visakapatnam, which is further up the coast. We’ll see what happens, but first things first I’m off to a place call’d Ooty tomorrow, a heat-avoiding hill station used by the British during the days of the Raj.

Day 68

There is an expression – about fuckin’ time – & after traipsing around the dusty libraries of the busy Tamil plains I have finally found a poet’s paradise. Writing in India is a weird experience – most of the time it’s just like London, where you can’t hear yourself think, but on occasion she’ll throw up situations & scenery to send the soul searing. My journey here began by taking the Niligris Mountain Railway up to Ooty – at a max speed of 33 KPH. It is very famous – & deservedly so –, & has UNESCO world heritage status. For all its fame it only cost me 4 rupees (5p). At Ooty, maybe fifty people got off – so that’s 200 rupees, or three quid generated for the company – it must be subsidised somewhere. The journey itself was very pleasant, climbing way up high up in the mountains, & as we broke out over the sheer drops it gave the sensation of flying through the air.

On the way to Ooty, about 17 k shy, we pass’d thro a place call’d Coonoor, which look’d really beautiful. Ooty itself was a bit of a dump, so I thought I’d stay in Coonoor instead, & set off on a glorious walk. I followed the train route, sometimes on the tracks, sometimes on little paths by the side, & didn’t get run over once. There was forest & vistas everywhere, punctured by the occasional cow or guy hacking at eucalyptus with a scimitar. The highlight of the walk was the epic expanse of the Ketty Valley, where little clusters of pastel houses trickle off toward the shadowy peaks far in the distance. It was very Scottish, like Avimore but sunnier. Every few kilometres I came across a wee station, which refreshed me with chi. At one of these, Lovedale, I had a great time, from playing on some kid’s fullsize drumkit, to meeting some genuine Todas.

There are only 1000 Todas alive today, & up until relatively recently were left to their little mountain kingdom. Then, 130 years ago, some British geezer saw the tea-growing potential of the climate & bought vast swathes of land for a rupee an acre. The Todas are buffalo herders & trinket makers, their main settlement being 10 miles away from Lovedale. Having donn’d my amateur anthropologist hat, I check’d out the three families that lived at Lovedale. One guy was a carrot farmer & as his wife fed us coffee (& tried to sell me knitted mobile phone holders). I discover’d he made 800 quid a year, but didn’t have to pay the government any taxes at all, what with him being a rare endangered tribe & all.

So, I arrived in Coonoor & took a room in a decent hotel. There are hardly any tourists & the scenery is just a tree or two short of Eden. The town is stacked against steep slopes, & is busy but not buzzin’. The view from my hotel looks over the stage-set centre of town &, best of all, there’s no fuckin mosquitos. After resting a bit, I took an evening stroll, feeling completely safe & unphazed. I don’t really wander about Indian streets at night, you’re always watching out for dodgy fuckers. However, this walk was inestimably peaceful, taking me to a wee suburb of Coonoor that clung to the sides of a deep river valley. Feeling my spirit relax for the first time in ages I sat down to soak in the atmosphere, just as the minaret of a wee mosque lit up & a local Imam began praising Allah. It was lovely to hear, especially as the holy song echoed around the vale. I wander’d about a bit more, the rivers rushing filling my ears, along narrow streets, past wee one floor houses with corrugated rooves & satellite dishes – then saw a sight I probably won’t forget ‘til I die. It was basically Siamese twin-dogs – joined at a buttock & just standing there doing fuck all – one with 3 legs & the other with 4. I went to stroke them, but the 4-legged one freaked out & began to drag the 3 legged one away. I watched all 7 legs kinda scamper away & mused upon God’s acid-taking.

Day 69

Today I was completely immers’d in flower-peppered walks, from lofty dams to fertile carroty valleys, as I work’d on the hardcopy Kural. The day began by hopping on an early bus & bantering away with loads of friendly school kids. The bus dropped me off 2k over Coonor & I then set off on a hike to the fabl’d Lambs Rock & Dolphins Nose, for apparently they had spectacular views. Unfortunately a thick cloud had fallen & I could see fuck all apart from the waterfall-dotted forest all about me. Then, when the road broke out of the trees, I found myself crossing the slopes of a massive tea plantation. I’d never seen tea growing before, & there wasn’t a drawstring bag to be seen. The tea bush is 2 foot tall, with green leaves 3-4 inch long & 1-2 inch wide. Somehow 3,500 years ago some of them fell into Chinaman’s cup of boiling water & hey presto, the magic brew. I also had a similar epiphany involving this magic herb. I needed a dump, so did one among some tea bushes. Then wiping with aforementioned leaves, I found them the smoothest I had ever used, better even than andrex extra-soft!

The whole are is really just one big tea plantation, peppered with little villages & rows of Butlins’ chalets to house the pickers (1.50 a day for 8 hours). British mountains are often purpley with heather or brown with bracken, but in comparison the Niligris are very, almost purely, green. The best way to describe the scenery is to picture normal British hill country, then cut a huge wedge of rock out of it a mile deep, then cover this with lush forest. Every ten yards a new vista opens up; from the immense white snakelike streak of water that hangs from Catherine Falls; to the view from Droog, which took in twenty miles of Niligris – the town of Coonoor the pastel-spangled jewel in its crown.

Further along the walk I came across a series of shops selling assorted teas – I tried a few, including a very delicious chocolatey one. Nearby by was a wee village call’d Karanci, very Italian, & clinging to a hilltop with the now clearing views of the Coimbatore plains far, far below. My gut instinct was to stay, & within half-an-hour had found a guy whose family are on holiday. He’s agreed to rent me a part of his bungalow tonight & tomorrow, & even cook for me – so my colonial dream has finally come true! I rang up the hotel to tell them I was staying here but to keep my room going.

Being up in such a peaceful spot help’d me gather my thoughts & after a bit of study I’ve found an ideal ashram for Charlie – who doesn’t know the plan yet, by the way. It’s called Pudupatthi, & tomorrow I’ll go down to Coonoor station to book us a couple of tickets – you need to think ahead in India, leading to the following sonnet. I also penn’d the following sonnet;

I took a breath or two of night-time air,

My heart not knowing why, my legs not where,

The starry skies obscured by gremlin cloud,

I headed for the hilltop temple loud,

Where rattled such a throng of Saivite,

Songs echoing thro ‘Niligrisian night,

Seeming another Tuscany to me,

For India oft felt like Italy,

& all was silver as a Silver Oak,

For searing thro the deep & astral smoke,

I found there was a full moon pulling clear,

These are the moments poets hold so dear,

Thro’ selene scenes setting dream-trails in store,

When ´morrow morns may pass these ways once more.

Day 70

Seventy days – wow that’s a lot. So I spent the latest of these at the delightful village of Karanci, perch’d beneath the Guernsey Tea Factory like some industrial-age Lancashire milltown. About a hundred houses cling to a sheer slope, with a temple at the top that rewards the hike up to it with wonderful views of the surrounding hills & the plains of Coimbatore. By day it’s kinda busy, but after 9PM the whole thing shuts down into a dogbark silence. There is this cute as fuck ‘high street,’ with little chicks fluffing about, & young goats warming themselves by a log-burner. There was a tailor, a chi shop, a wee place to get some food & a little grocers. For the first time in two months I bought some fruit & veg & made a meal using ‘mutton masala’ for the spicy sauce. It wasn’t bad either, tho’ my landlord Deva wouldn’t touch it with a barge pole & got annoyed every time I tried to wash up.

Saying that, my host was magic. I think he appreciated the company while his family is on holiday, plus the celebrity the village gossips gave him in having the first ever tourist (possibly) to actually sleep in the village. He’s a very simple man who earns a couple of quid a day working at the tea plaza next door. Every lunchtime, for about two hours, he shows a steady stream of tourist buses in for the obligatory cup of chi. The rest of the time he just potter’d about, calling me ‘sir’ all the time. On one occasion this afternoon I was watching Friends on TV & he came in & disapproved of the kissing on it. I’ve now found out that Christian Tamils don’t kiss – not even during lovemaking. In fact, I don’t think they do that either. To keep warm he sleeps with his daughter all his life & his wife sleeps with their son – all in the same room (which I’ve now got). He asked me if I was married, & I said I’ve been seeing someone five years, & he goes “but you’re not married – I suppose you have spent five years just talking then, sir!”

After my wee Friendsathon, I borrow’d Deva’s scooter & rode down to Coonoor to buy the Pudupatthi tickets, a frustrating experience which led to the penning of the following sonnet;

Such heaps of despatch boxes, such mounds of record boxes,

Such vast fabrics of pigeon holes, such abandon of red tape

William Howard Russell

I found myself waiting at this train station,

Not for a train, it was just to buy a ticket,

Not even for that day, but eleven in the future,

The next one available from Cochin to Calicut;

& I´m waiting & I’m waiting & I´m waiting nit-pick longer,

& the guy behind the desk´s on his third guy in an hour

& I was fourth, but the seventh guy´s hand starts waving

His reservation form as the third guy was about to finish;

So, I warned fifth, sixth, & seventh they´d be foolish for linecuttin,’

After all, I’d bin in the sun all day like a mad English dog

& my legs felt like lead & I was definitely, definitely, goin’ next…

So, the third guy finishes, & just as I thrust my form thro’ the window

The fella behind the desk decides he needs the fuckin’ toilet…

Then, when he’d finish’d, the scoundrel closes the window fer lunch!

On the rising of the full moon, & with it being my last night in the Niligris, I went out for a midnight hike in the epic, creaking Eucalyptus forests that climb out of the thick knots of Acacias like ballet dancers rising from the waves. Twenty minutes into my walk a car stopped & this gruff voice asked me where I was going. It turns out the forests are full of wild animals – cheetahs, panthers, charging bison, etc. – & I was sure to become one of the daily ‘incidents’ that plague the area. Suffice it to say I got a lift back to Karanci with them & from that moment on stuck firmly to my room.

Adventures on an Indian Visa (week 9): Transcreation

Day 57

After a refreshing morning’s swim & lunch at a local resort, I left Mamallapuram & bobbl’d slowly into busy Chidambaram. Last week it was still underwater after the cyclone hit, but it has recently resurfaced & looks much the cleaner for it. After a first sweep I didn’t find much on offer in the way of accommodation, & ended up holing up in a pretty shitty room for the night – it looks & smells like it hadn’t been cleaned in years. However, there is a magazine cut-out picture of the Niagara Falls sellotaped to the walls – which I’d never actually seen, so it was kinda worth it. Another slight drawback is having to put up with the constant smell of fried batter rising upwards into my room from the street. It smells just like a chippy, which got me dreaming of a decent chips & curry, but has turn’d out in fact to be a wee crisp factory. I did actually try a fresh bag & they were pretty delicious, to be fair.

On the outskirts of town is the Annamalai University. My intention was to use their library & conduct a deeper delve into Tamil studies & also use it as a base to continue my transcreation of Thirukural. Alas, I have discover’d out that any foreign national wanting to enter even the campus of an Indian university has to have special permission, which takes about three weeks to process. I found this after an afternoon of typical, long-drawn out Indian bureaucracy, which ended up with me waiting to meet the vice-chancellor of the university. I was surrounded by professors & uni types, but that didn’t seem put any cordiality on affairs, as the queue – as all Indian queues do – ended up as a rugby scrum to get to the front. After about two hours of this I thought fuck it, throwing my innate sense of English fairplay out of the window & dived to the front like a buxom fly-half. Ten minutes later, sat in a plush seat in an even plusher room, the portraits of dark-skinned past chancellors staring down at me from the walls, I could feel their burning eyes penetrating into my skull & seeing that my ‘formal’ higher education boiled down to only six months of getting wasted at Barnsley college on a foundation course for a music degree.

After putting my case forward, for all my bravado & the fact I’d had a shave & everything, I was, with all respect, told, in no uncertain terms, to fuck off. My demands to see the chancellor – his boss – were refused, on the grounds that the chancellor represents the whole state, lives in Chennai & only popped in once a year. ‘Get him on the phone,’ I asked – ‘there’s the door.’ he replied. As I walked back through the 900 acre site of the uni, past all the pink building faculties & the vast bladerunner style massive mansion where the vice-wanker-chancellor lives, it seemed like all the students were taking the piss out of me, my academic plans in complete tatters.

Still, you don’t become a poet by not being resourceful – a lack of genuine & constant wages needs to be overcome somehow -, & my non-admittance to the dusty corridors of education proved a lucky break. I decided to seek out the local library, getting there on the back of a probably drunken Tamil guy’s bike. In its depths I discovered a recent version of Thirukural – one that the ancyent, page-molding books of libraries at Tiruvanamali & the University (I checked yesterday) would never have. It’s a very comprehensive, double-tomed 1500 page affair which I now have in my actual possession. I had to leave 500 rupees & my passport with the overhappy librarian, but it’s worth it, for I now have a wicked reference book for this final effort to finish the poem. I’ve got about 475 kural left to do, which I’ll probably finish in a week at my current pace.

Near the library was a nice hotel & I shall move in their tomorrow morning – just in time to a one-dayer between India & England, plus the weekend’s footy. It’s quite comfy actually, & only costs 100 rupees more than the one I’m staying in – a quid ! I’ve also got some interesting news – I’m writing this in an internet café & I’ve just had an email from my mate in London, Charlie, who wants to join me in India. He’s already got a visa & everything & just wants to find the nearest airport to me. So I’ve said Chennai, mate, see you when you get here.

Day 58

I was walking down the road today when it suddenly dawned on me that I’d just seen my millionth moustache in Tamil Nadu. It wasn’t announced with fanfares, streamers & a quick trolley-dash around Woolworths (RIP), it was just my subliminal consciousness kicking in. I mean, man, they’re everywhere; about 99 percent of males have them. This tash-equality makes Tamil Nadu a nice place to wander about in, as opposed to other parts of India where the caste system is clearly visible. Alright, you’ve got your beggars & the street cleaning women, but everyone else seems to be much the same & getting on with life in happy harmony. The state is also very proud of its place in the world. A wee look on the map & you can see that Tamil Nadu is remarkably similar to the Irish landmass – in size, & shape & also, I find, in spirit. This strong sense of patriotic self-identity was born out of repelling the Indo-Aryan invasions 3000 years ago, plus several attempts by the various owners of Delhi to conquer & impose Hindi as the national Indian language. Which of course, they never did – the Tamil language is strong, alive, river-flowing & beautiful.

‘My Tamil is very bad,’ said Ryan Germick, ‘& the sign painter I work’d with didn’t know any English. We mostly communicated through sign language. But we discussed everything from atheism to the nature of art.’ That pretty much nails it in the head really – what a cool, cultur’d people. Anyway, here is the Tamil I have learnt so far, condens’d into a sonnet;

1 Woner = Wanacum (hello)

2 Render = Nan-dray (thanks)

3 Mooner = Yevolovum (how much)

4 Nar-lee =Rumba Soo-aye (very tasty)

5 An-jer = Time Enna (what time is it)

6 Ah-roo = Poy-too-varen (see you later)

7 Air-lee = Oon Pair Enna (what is your name)

8 Eh-ta = Nar England (I am from England)

9 Umbodoo = Nalla –kay (tomorrow)

10 Pa-too = Ama (yes)

11 Padi-nooner = Ill-ai (no)

12 Panander = Nunbar Nan-dray (grazi raggazi)

13 Padi-mooner = Nalamar (how are you)

14 Padi-nar-lee = po-dum (full/enough)