The Young Shakespeare (15): Upstart Crow

1590

AUTUMN

Shakespeare in Titchfield

According to Aubrey, Shakespeare had been, ‘in his younger yeares a schoolmaster in the countrey,’ but when? In 1590, Shakespeare’s ‘younger years’ are running out somewhat, & we only have two more years to go until he is a smash-hot dramatist & the talk of all London. A year later, in 1593, he is dedicating his first poetic effort, Venus & Adonis, to a young English nobleman called Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd Earl of Southampton, in which he describes his ‘unpolished lines’ as being written during his ‘idle hours’. The question is, what was Shakespeare doing when he was not being idle?

The answer is he was tutoring the seventeen year old earl, who disappears from the records between October 1590 and August 1591. He was, in fact, living in Titchfield, where his pro-Catholic mother, Countess Mary, was in residence at Titchfield House. His contact now with Shakespeare would blossom into a great friendship, with Nicholas Rowe describing how the bard;

Had the honour to meet with many great and uncommon marks of favour and friendship from the Earl of Southampton… there is one instance so singular in the magnificence of this patron of Shakespeare’s, that if I had not been assured that the story was handed down by Sir William D’Avenant, who was probably very well acquainted with his affairs, I should not have ventured to have inserted, that my Lord Southampton, at one time, gave him a thousand pounds to enable him to go through with a purchase which he heard he had a mind to. A bounty very great and very rare at any time, and almost equal to that profuse generosity the present age has shown to French dancers and Italian eunuchs.

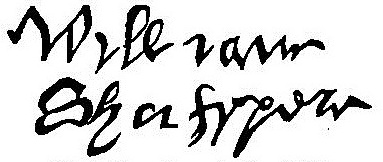

Finally, a possible & oblique connection between Shakespeare & Southampton is found in a 1592 letter from the Third Earl of Southampton is signed by him, but penned by somebody else. An American hand-writing expert, Charles Hamilton, has suggested the handwriting is identical to a portion of the manuscript of The Play of Sir Thomas More, which lies on solid ground enough in the world of Shakespearean scholarship to be given as the bard’s own hand.

It is now time to introduce a new dimension to the sonnets, a layer to Hisalrik if you will. We have established so far that Shakespeare wrote sonnets to William Stanley & to the mysterious Turkish lady in Constantinople. I am a sonneteer myself, & understand how individual sonnets composed to different persons may be synthesised into a paean to a single ‘ideal’ within a sequence. In the same spirit, a small number of the sonnets were composed to Southampton, those in which Shakespeare takes on the role of the older man urging the younger aristocrat to marry & have children. These are known as the ‘Procreation Sonnets,’ & form the first 17 of the 154 strong sequence.

There is a significant back story. Thomas Wriothesley, second Earl of Southampton, and father of Shakespeare’s patron, died on 4th October 1581, leaving the seven year old Henry as his only surviving son. Elizabethan law deign’d him to become a ward of the Crown, & placed him in the hands of a certain Lord Burghley who would in 1589 put huge pressure on the young earl to marry his own grand-daughter, Lady Elizabeth Vere, the daughter of the Earl of Oxford of antishakespearean fame. In 1591, John Clapham – one of Burghley’s secretaries compos’d & dedicates a poem called Narcissus to Southampton, which concerns a handsome youth who had fallen in love with own reflection. Shakespeare would handle the handsome youth motif differently, instead suggesting it was Southampton’s duty to marry & continue his beautiful physical lineage.

1590

DECEMBER

The Tears of the Muses

Shakespeare’s presence in Hampshire follow’d hard on the heels of Edmund Spenser himself, who was there in 1590. The poet Samuel Woodford, who lived in Hampshire near Alton, told Aubrey that, ‘Mr. Spenser lived sometime in these parts, in this delicate sweet air; where he enjoyed his muse, and wrote a good part of his verses.’ Some of these verses were included volume of poems called The Tears of the Muses, registered on the 29th December, 1590. They were dedicated to a relation of the poet’s, Alice Spencer of Althorp, who had married William Stanley’s brother, Ferdinando. , which in the scheme of our survey shows an increasingly narrowing world!

In one of the stanzas of Spenser’s new poem, we see the return of the same ‘Willy’ who inhabited the 1578 Calendar.

And he, the man, whom Nature self had mad

To mock herself, and Truth to imitate,

With kindly counter under mimic shade,

Our pleasant Willy, ah! is dead of late:

With whom all joy and jolly merriment

Is also deaded, and in dolour drent.

But that same gentle spirit, from whose pen

Large streams of honey and sweet nectar flow

Scorning the boldness of such base-born men,

Which dare their follies forth so rashly throw;

Doth rather choose to sit in idle cell,

Than so himself to mockery to sell

That he is deem’d ‘our pleasant Willy‘ suggests a connection to both Alice and Edmund Spenser, which is confirmed through bond of blood, for Shakespeare’s mother was distantly related to the Spensers. Spenser’s description of ‘large streams of honey and sweet nectar,’ is reminiscent & contemporaneous with Francis Meres’ description of Shakespeare in the Palladis Tamia as ‘mellifluous & honey-tongued.’ That Shakespeare was ‘dead of late‘ indicates him as being between creative periods, while the ‘cell’ mentioned by Spenser points to Shakespeare’s taking up of a position as tutor to the Earl of Southampton. The cell seems to refer to a house near Titchfield Abbey, known as Place House Cottage, which was a schoolhouse at the time & where Shakespeare might have slept.

1591

SPRING

Shakespeare writes Edmund Ironside

The Earls of Southampton clearly enjoyed the Theatre – plans of 1737 show a large room on the upper level of Titchfield House labelled as ‘Play House Room.’ The tradition of theatre-making at Titchfield stretched back to before its Abbey had been converted to a stately home. In 1538, one of Thomas Wriothesley’s servants wrote to him, describing how Thomas’s future wife, Jane, ‘handleth the country gentlemen, the farmers and their wives to your great worship and every night is as merry as can be with Christmas plays and masques with Anthony Gedge and other of your servants.’

During Shakespeare’s time at Titchfield he created a play call’d Edmund Ironside, rapidly cobbling together a variant of his Titus Andronicus for a new audience, & setting it in Hampshire – the opening scene is in Southampton, while the Earls of Southampton are the main protagonists. It is likely he found the story in Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland – published in 1577, and again in 1587 – perhaps even in the libraries of Titchfield. Another source appears to be William Lambarde’s Archaionomia [Ancient Laws], a collection of Anglo-Saxon customs and laws that he translated and published in 1568, & of course the county of Hampshire is at the very of Anglo-Saxon England, with Winchester being the former capital of Wessex, from where Alfred The Great issued his laws. Fascinatingly, in the 1940s a copy of the Archaionomia was found with ‘Wm Shakespeare’ scrawled across the title page in what is basically Shakespeare’s signature…

Still in the library of Titchfield, according to Randall Martin, Ironside is a very bookish piece, inspired by Thomas Hughes’s neo-senecan tragedy, The Misfortunes of Arthur (1588), John Heywood’s play The Pardoner and the frere, Spenser’s Faerie Queene (published in 1590) – the source for several unusual words and phrases – & William Warner’s verse-chronicle Albion’s England (1586) as the source of “smaller details of character and situation”

To modern scholars, Edmond Ironside is a mysterious & anonymous play, with no records of performance in the period, suggesting, of course, its creation for a private performance. They all concur on one thing, however, that its a rather crude & organized piece, with meandering plotline & irrelevant speeches and scenes throughout. The manuscript was discovered in 1865, when the British Museum purchased fifteen play manuscripts bound together into a single volume from a private library, known as Egerton 1994. Ironside certainly feels like it is bubbling up from a thinking Shakespeare – for it possesses familiarities with the Law, the Bible, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and country life, as does most of Shakespeare’s work. Meanwhile scholars have suggested it was written by him for the following linguistic reasons;

* There are 260 words that were used first by Shakespeare

* There are 635 instances of Shakespearean rare words

* There are 300 usages of the very rarest Shakespearean words

* There are 700 clear parrallels with the first folio

* There are 350 verbatim phrases

The most considerable echoes can be found in Titus & the Henry VI plays, & placing Shakespeare writing Edmund Ironside in Hampshire after Titus & before he began work on his famous cycle of Histories makes perfect sense. Thus, creating Edmund Ironside would be a catalytical moment for Shakespeare – it was his first attempt at writing English history, & within days. one expects, he began work on the trilogy of plays to Henry VI that would make his name & shoot his talents into the stratosphere. Indeed, when in Ironside we hear the following phrases: “this noble isle,” “my pleasure’s paradise,” “the fortress of my crown,” “this little world,” “this little isle,” “this solitary isle,” “this realm of England,” we also hear echoes of Shakespeare’s famous phrases, such as, “this sceptered isle,” “demi-paradise,” “this fortress,” “this little world,” “this precious stone set in the silver sea,” “this realm, this England.”

Examining Ironside in more detail, we may observe that it shares with Titus a theme of rival candidates vying for a crown, while making mainstream some of the Roman play’s more tributary plots. There can also be made solid comparisons between the Edricus of Edmund Ironside & Joan Of Arc from 1H6. In his ‘Shakespeare’s Lost Play, Edmund Ironside,’ Eric Sams describes how it, ‘contains some 260 words or usages which on the evidence of the Oxford English Dictionary were first used by Shakespeare himself, with the strong presumption that it was he who coined them. Further, it exhibits 635 instances of Shakespeare’s rare words including some 300 of the very rarest, and 700 clear parallels with the First Folio, including 350 phrases shared verbatim. All these features are found most frequently in the earliest canonical plays of circa 1590. So the young Shakespeare is an obvious suspect.’ In his ‘EDMOND IRONSIDE, THE ENGLISH KING’, RL Jiménez has plenty more to say on the topic;

If Ironside includes and anticipates not just one, and not just a handful, but over 260 examples of words, usages, locutions and ideas which the OED attributes to Shakespeare as his first coinages.’

Edmund enters during a conversation begun off-stage, as often in Shakespeare

To compare one’s own characters with Judas and Jesus, in deliberate reference to the Gospel account of the betrayal, to make amusing puns on the actual words used, and above all to put the words of Jesus into the mouth of Judas; these characteristics identify the young Shakespeare in three separate plays (3H6, R2, LLL) of the early 1590s.

On any analysis, Shakespeare at the time of Titus c. 1589 was steeped in Ovid, including Book I (banquet of Lycaon, story of Io) as well as III (Actaeon), XIII (Hecuba) and so probably X (Orpheus) as well. The same is true of the author of Ironside c. 1588. Unless it is safe to assume that two Tudor dramatists showed the same concentration on the same books of the same works of the same poet at the same time there is a good case for identification on those grounds alone.

Edricus delivers a fifty-line soliloquy in the manner of Richard III, Iago, or Aaron in Titus Andronicus, in which he recounts what a villain he is

In a scene even shorter than the nearly identical one in the last act of Shakespeare’s Henry V, Canute meets Egina, offers her a cup of wine, and proposes––all in the space of thirty lines.

A leading scholar of the Elizabethan drama, Frederick Boas, observed that the dramatist portrayed Edricus as a “Machiavellian intriguer” who has the “stamp of Renaissance Italy rather than of Anglo-Saxon England”

Hendiadys––where two words expressing the same idea are joined by a conjunction––is another rhetorical device that Shakespeare used abundantly in his early writings. Albert Feuillerat found 86 examples, such as “reek and smoke,” “shake and shudder,” “dread and fear,” and “repose and rest,” in Venus and Adonis and Lucrece(61-2). They are relatively rare in Marlowe, but appear in profusion throughout Edmond Ironside––6 in the first scene alone.

Dozens of images, themes, and symbols found in both the anonymous play and in his accepted works, especially in the early plays, attest to the thought patterns of a single mind: people likened to plants, insects, birds and beasts of all kinds; blood that is shed or drunk; severed heads; soldiers who stand watch, who desert, who are betrayed, or deprived of necessities; evil and traitorous flatterers; emotional women; stubborn Jews; kings who are betrayed and rant about Judas; vows of revenge; children parting from their mothers; portents in the skies; plots that hammer in the head; passions that boil, rage, or ignite; feigned laughter; dark sighs; salt tears; Troy ablaze, etc. There are over seventy such motifs in Ironside that are repeated in Titus Andronicus, Henry VI, Parts I, II, and III, Richard II, and Richard III

In Act IV of Ironside, Emma recounts her anguish as she tearfully dispatches her two small sons to Normandy for safekeeping:

to dam my eyes were but to drown my heart like Hecuba the woeful queen of Troy who having no avoidance of her grief ran mad for sorrow ’cause she could not weep (1477-80)

In Titus Andronicus, as the ravished and mutilated Lavinia runs after him, the young Lucius struggles to understand her grief:

I have heard my grandsire say full oft extremity of griefs would make men mad

and I have read that Hecuba of Troy ran mad for sorrow. (4.1.18-21)

Another example is Canute’s comparison of the destruction he will wreak upon “new Troy” (London) with that suffered by ancient Troy, which he describes as “consumed to ashes and to coals/ with flaming fire . . . ” Similar references to Troy-on-fire are scattered throughout Shakespeare’s works: five in Lucrece (1468, 1474-6, 1491, 1523-4, 1561); three in Titus Andronicus (3.1.70, 3.2.28, 5.3.84); two in Henry VI, Part 2 (1.4.17, 3.2.118); and one each in Henry IV, Part 2 (1.1.73), Julius Caesar (1.2.113), and Hamlet (2.2.466).

The dramatist also specifies the weapon––an axe, unmentioned in the chronicles. Stich is the execu- tioner, and the “Ha. Ha. Ha.” reaction of Edricus, followed by Canute’s question, “Why laughest thou, Edricus?” are identical to similar laughs and questions after similar gruesome acts in Henry VI, Part I (2.2.42-3), and Titus Andronicus (3.1.65). The brutal mutilation scene extends to more than 160 lines. As Boas says, “No detail of physical horror is spared; the atmosphere is as foul and asphyxiating as in the notorious scenes in Titus Andronicus”

Act III opens with another irrelevant scene that is unique in Elizabethan drama. It is a vicious and abusive quarrel between the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, who are presented in their historical positions on opposite sides of the war. The Archbishop of Canterbury, who favors Canute, asserts his authority over York, calls him an “irreligious prelate,” and demands that he yield to him. The Archbishop of York replies by calling Canterbury a traitor, a rebel, a betrayer of his King, a profane priest, a Pharisee, and a parasite. After three exchanges of this type, York flees the stage and Canterbury follows, threatening to club him. Neither is heard from again. A similar exchange occurs in the third scene of Act I of Henry VI, Part I between Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester and Lord Protector of the King, and his rival, Henry Beaufort, the Bishop of Winchester. The language and the level of invective are remarkably similar, and there are identical threats of violence.

Finally, & quite significantly as appertaining to my investigation, having begun to believe that Shakespeare had transcribed the Mystery Plays in Burnley, Sams says;

As commentators have noted, however, Judas does indeed greet Jesus thus {all hail} in certain surviving texts of the mediaeval Mystery Play both at York (Schoenbaum, 1975, 48) and Chester (Milward, 1973, 33). There are strong independent grounds for supposing that Shakespeare had indeed seen such plays, already outmoded in his lifetime but still surviving in certain centres during his younger years; he refers to them in such phrases as ‘it out-Herods Herod’, ‘the old Vice’, and so on.

1591

SUMMER

Shakespeare begins the History Cycle

Shakespeare’s great sequence of history plays covers pretty much the whole of the dynastic War of the Roses, that dividing of England & Englishness which ran & ran & ran for deacdes of division, slaughter & power politics. The conflict was fought our between two royal houses, that of Lancaster & that of York, & ‘there is general agreement,‘ writes Lefranc, ‘that Shakespeare, in the historical dramas he devoted to the wars of the Roses, in spite of his usual impartiality, shows himself Lancastrian.’ This makes sense, for Shakespeare’s own great-grandfather fought at Bosworth field on the side of Henry Tudor, as suggested by Shakespeare’s father when he applied to the College of Heralds for a family coat of arms in 1596. A draft prepared by William Dethick, the garter king-of-arms, declared by ‘credible report’ that John Shakespeare’s, ‘parentes & late antecessors were for their valeant & faithfull service advanced & rewarded by the most prudent prince King Henry the seventh of famous memorie, sythence whiche tyme they have contiewed at those partes in good reputacion & credit.’

‘Shakespeare rearranged history,‘ says E. A. J. Honigmann ‘so as to make Stanley’s services to the incoming Tudor dynasty seem more momentous than they really were.’ The History plays definitely inflate the role of the Stanleys in the creation of the Tudor state, which end of course a Stanley-sponsored Shakespeare would achieve. The 1st Earl of Derby, Thomas Stanley, was created as such by Henry VII after the Battle of Bosworth, which role was dramatized in Richard III. Shakespeare famously portrays Richard III as a heinous villain, which was handy for the Stanleys seeing as Thomas & his kinsman, William, both betrayed the last Plantaganet king at Bosworth. This led to the moment when the whole Tudor dynasty began, as Thomas Stanley pluck’d the crown from the dead Richard and then places it on Henry’s head.

Taking his matter from Raphael Holinshed’s ‘Chronicles of England, Scotlande, & Irelande,’ our bard wove together a wonderful piece of drama in which he ressurected history & brought it alive like no other had done before. Not long after seeing it, Thomas Nashe wrote;

How would it have joyed brave Talbot, the terror of the French, to think that after he had lain two hundred years in his tomb, he should triumph again on the stage, and have his bones new embalmed with the tears of ten thousand spectators at least (at several times) who in the tragedian that represents his person imagine they behold him fresh bleeding.

Significantly, John Talbot was also the name of William Stanley’s very good friend, John Talbot, who would be later knighted by King James at Lathom House itself.

When creating his history cycle, Shakespeare drew from his time spent with the Queen’s Players, & especially one of the plays in their repertoire, The Famous Victories of Henry V. We know it was theirs as on its publication in 1598, the play was advertised as acted by ‘her Queen’s Majesty’s Players.’ C.A. Greer points out fifteen plot elements of the Famous Victories that are to be found with greater detail in the trilogy. These include the robbery at Gad’s Hill of the King’s receivers, the meeting of the robbers in an Eastcheap Tavern, the reconciliation of the newly crowned King Henry V with the Chief Justice, the gift of tennis balls from the Dauphin, and Pistol’s encounter with a French soldier (Dericke’s in The Famous Victories).

Another ‘anonymous’ history play might be included in the Shakespearean canon. Printed in 1596, Edward III was at least co-author’d by Shakespeare. What is interesting is that it contains several gibes at Scotland and the Scottish people, which might reflect the bard’s own experience of his time at the court of King James. This could also explain why the play was not included in the First Folio of Shakespeare’s works, which was published after the Scottish King James had succeeded to the English throne in 1603. If Macbeth is the ‘Scottish Play,’ then Edward III is the ‘anti-Scottish play.’ Accepted by modern scholars as authentic Shakespeare, the tradition goes back to at least 1760, when Edward Capell suggested as much in his ‘Prolusions; or, Select Pieces of Ancient Poetry, Compil’d with great Care from their several Originals, and Offer’d to the Publicke as Specimens of the Integrity that should be Found in the Editions of worthy Authors.‘ There are even passages which are direct quotes from Shakespeare’s sonnets, most notably the line “lilies that fester smell far worse than weeds” (sonnet 94) and the phrase “scarlet ornaments”, as used in sonnet 142.

1591

AUTUMN

Shakespeare meets John Florio

John Florio was the most famous Italian in Elizabethan England. He was also a tutor to the Earl of Southampton at some point… the dates have never been established. We do know that in his Italian-English dictionary publish’d in 1598, he states he had lived ‘some yeeres ‘ in the ‘paie & patronage‘ of the earl as his tutor in Italian & French. It is possible to get to the key date of 1591 thro a single sonnet which appears in the introduction to Florio’s book, ‘Second Frutes.’ This series of discussions in Italian contains, in the second dialogue, two speakers call’d John & Henry, clearly mirroring Florio & The Earl of Southampton. Indeed, the topics touched on in the Second Fruits, like primero, the theatre, love, and tennis, represent Southampton’s tastes.

Phaeton to his Friend Florio

Sweet friend, whose name agrees with thy increase

How fit a rival art thou of the spring!

For when each branch hath left his flourishing,

And green-locked summer’s shady pleasures cease,

She makes the winter’s storms repose in peace

And spends her franchise on each living thing:

The daisies spout, the little birds do sing,

Herbs, gums, and plants do vaunt of their release.

So when that all our English wits lay dead

(Except the laurel that is evergreen)

Thou with thy fruits our barrenness o’erspread

And set thy flowery pleasance to be seen.

Such fruits, such flowerets of morality

Were ne’er befroe brought out of Italy.

This is an excellent sonnet, fermenting nicely with Shakespearean terms, conceits, and images. Indeed, just as the Phaeton sonnet and Shakespeare’s Sonnet 1 both end their first lines with increase, so the Phaeton sonnet and Sonnet 1 both rhyme on spring. In The Life and Times of William Shakespeare, Levi opines, “no other writer of sonnets is as good as this except Spenser, but Spenser would have signed it. The humour is Shakespeare’s, and so is the movement of thought, so is the seasonal coloring.” What is not Shakespeare’s is the rhyme scheme – it uses the “Spenserian” “abba abba cdcdee” instead of his preferred “abab cdcd efef gg”. But in 1591 Spenser was all the rage & in Hampshire, so…

Sonnets 97 and 98 are surely the work of the same hand that wrote the Phaeton sonnet, which they echo in the words winter, pleasure, bareness, summer’s, increase, decease, fruit, birds, sing, spring, sweet, flowers, shadow, and various synonyms and paraphrases. Line 11’s ‘o’erspread’ reflects Shakespeare’s fondness for the prefix o’er; the Sonnets give us o’ercharg’d, o’ergreen, o’erpress’d, o’ersnow’d, o’ersways, and o’erworn, among other constructions. Elsewhere, his plays boast such odd coinages as o’erwrastling and o’erstunk! Line 4’s ‘and green-locked summer’s shady pleasures cease,‘ feels very Shakespearean. Compare Sonnet 18: “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” See also “Making no summer of another’s green” (68); “The summer’s flower is to the summer sweet” (94); “For summer and his pleasures wait on thee” (97); and this quatrain from 12:

When lofty trees I see barren of leaves,

Which erst from heat did canopy the herd,

And summer’s green all girded up in sheaves,

Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard.

Phaeton is found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the son of Phoebus Apollo who drives his father’s chariot, only to scorch the earth and fall to his death. An accident then, which leads to Sonnet 37 & Shakespeare’s mentioning of him in a tutor-like, fatherly role, & having been ‘made lame by fortune’s dearest spite.’ Was this why Shakespeare was in the country – recuperating from a broken leg or something!

As a decrepit father takes delight

To see his active child do deeds of youth,

So I, made lame by fortune’s dearest spite,

Take all my comfort of thy worth and truth.

For whether beauty, birth, or wealth, or wit,

Or any of these all, or all, or more,

Entitled in thy parts do crowned sit,

I make my love engrafted to this store:

So then I am not lame, poor, nor despised,

Whilst that this shadow doth such substance give

That I in thy abundance am sufficed

And by a part of all thy glory live.

Look, what is best, that best I wish in thee:

This wish I have; then ten times happy me!

1591-92

Shakespeare Begins Romeo & Juliet

Another play that Shakespeare was working on at Titchfield is that famous tale of star-crossed lovers, Romeo & Juliet. We know it was written befor 1595, & a line uttered by Juliet’s nurse gives us a credible date.

‘Tis since the earthquake now eleven years

In April 1580, a magnitude 5.5 earthquake caused extensive damage in the south-east of England and in London, two people were killed. If this is the earthquake Shakespeare is referring to, then Romeo & Juliet is being written in 1591. It is also being written the following year, as it contains nods to a 1592 romance by Samuel Daniel called The Complaint of Rosamond; the relevant passages include the description by Rosamond’s ghost of her death by poison and of Henry II’s mourning at his mistress’s bier (603-79) which remerges in Romeo’s lament over Juliet’s body (V.iii.92-115). In Daniel, a few line later, he gives us Rosamund’s epitaph;

And after ages monuments shall find, Shewing thy beauties title not thy name, Rose of the world that sweetned so the same.

We here see wordplay on Rosamund’s name – where her ‘beauties title’ (rosa mundi) is not her real name (rosa munda). These, & the word ‘sweetened’ leads us naturally to Juliet’s famous declaration;

O, be some other name! What’s in a name? That which we call a rose By any other name would smell as sweet; So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call’d, Retain that dear perfection which he owes Without that title.

Romeo & Juliet would have resonated with the Southampton family, The Third Earl’s maternal grandfather, Antony Browne, was a pal of King Philip II of Spain, who created him Viscount Montague in September, 1554. Romeo & Juliet, of course, is a play which features a feud between the Montagues & the Capulets! A forbidden, homosexual love between Southampton & Shakespeare may only be speculated on,& might be a feature embedded in the play, but there is no proof… as of yet.

In Romeo & Juliet we can a taste a little of Shakespeare;’s Grand Tour with Stanley. Romeo’s expresses his love via the metaphors of the sonneteering Petrarchist school of Serafino Aquilano. In a tragedy by Luigi Groto, the Adriana (publ. 1578), which is also inspired by the story of Romeo and Juliet, two passages spoken by a character call’d Latino contain similes used by Romeo, while also mentioning a nightingale in the parting scene.

1592

FEBRUARY

The Premier of Shakespeare’s Battle of Alcazar

Philip Henslowe was a London businessman who built the Rose playhouse in 1587. He also kept a priceless of diary of plays & their takings which contains some of Shakespeare’s debuts. Here’s the Spring season of 1592;

February

19 – fryer bacone & friar bungay –

20 – muly mulloco

21 – Orlando –

23 – Don Horatio

24 – Sir John Mandeville

25 – Harey of Cornwall

26 – The Jew of Malta

28 – Clorys & Orgasto

March

2 – Matchavell

3 – henry Vi

4 – Pope John

4 – Bendo & Richardo

6 – 4 plays in one

8 – The looking glass

9 – Zenobia

14 – Jeronimo

21 – Constantine

22 – Jerusalem

April

6 – Brandymer

10 – the comedy of jeronimo

11 – titus & vespasian 3 – 4 – 0

28 – tamberlayne part 2 – 3 4 – 0

28 – the tanner of denmark –

The second of these plays, muly mulloco, perform’d on the 21st of February, & should be the same as a play first performed by Lord Strange’s Men call’d the ‘The Battell of Alcazar’ as one of the characters in the play refers to another as ‘Muly Molucco,’ a name which appears nowhere else in Elizabethan drama. The play’s proper title, as printed in its quarto edition, is ‘The Battell of Alcazar, fought in Barbarie, between Sebastian king of Portugal, and Abdelmelec king of Marocco.‘

Topical references to the Armada suggest the play was written 1588-1589 & there are traces of Stanley-Shakepeare coauthorship. When in North Africa together, they would have listened to tales of the Battle of Ksar El Kebir (Alcazar), fought in northern Morocco on the 4th of August 1578. Brian Vickers shows numerous verbal echoes between the co-authored parts of Titus Andronicus & the Alcazar including a highly similar double consonantal alliteration. Macdonald P Jackson also highights how the weird formalities of the first Act of Titus have been mirrored by those of the Alcazar.

1592

MARCH

A Star is Born

In early 1592, the world at large became witness to Henry VI part 1, performed by Ferdinando Stanley’s Lord Strange’s Men. This makes Lord Strange’s Men the first acting company to be ‘officially’ associated with a Shakespeare play. After an unprecedented six performaces at court over the winter season, they began playing in the capital’s theatres, including the Rose, which had opened on February 19th, 1592. In his diary, the Rose’s theatre manager, Philip Henslowe recorded quite succinctly that on the 3rd March 1592, he had seen a ‘ne’ play called ‘Harey the vj.’ This play seems to be Henry VI part 1 by Shakespeare, for in the August of that year, in his Pierce Penniless, Thomas Nashe refers to a play he had recently seen which featured a rousing depiction of Lord Talbot, a major character in Henry VI part 1. Takings for ‘Harey the vj.’ were three pounds, sixteen shillings & eightpence, which equates to 16,444 pennies in the ‘box’ – a clear hit! I mean lets be honest, the paying public would have been amazed, there was a new kid on the block & Shakespeare had thrust himself onto the public imagination in much the same way George Lucas did with his Star Wars trilogy.

1592

SUMMER-AUTUMN

Shakespeare attacked by Greene

Shakespeare’s plays were clearly a hit, but true fame is always laced with a splash of envious outside spite. Enter fellow playwright, Robert Greene who, writing practically on his deathbed, vilifies Shakespeare in his Groatsworth of Wit as, ‘an vpstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers hart wrapt in a Players hyde, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blanke verse as the best of you: and beeing an absolute Iohannes fac totum, is in his owne conceit the onely Shake-scene in a countrey.’ The reference to Shakespeare being a jack of all trades, a ‘johannes fac totum,’ could well be implying his status as Southampton’s teacher. By parodying Shakespeare’s line ‘O tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide,‘ (Henry VI, part 3), it is clear Greene is alluding to Shakespeare in quite jealous tones.

In the same pamphlet, Greene seems also to refer to Shakespeare’s participation with the Queen’s Players, on whose formation in 1583 were given the title, ‘grooms of the chamber.’ Greene writes; ‘it is pity men of such rare wits [Nashe, Marlowe and Peele] should be subject to the pleasures of such rude grooms.’ The old order was dying, Robert Greene would pass away on the 2nd September 1592, by which time a completely new form of theatre was springing up about the marvellous & remarkable quill of an ‘uneducated’ Warwickshire yeoman. By the end of the year, even Greene’s publisher was climbing aboard the bandwagon, when in a preface to Kind-Harts Dreame by Henry Chettle, we find;

About three moneths since died M. Robert Greene, leauing many papers in sundry Booke sellers hands, among other his Groatsworth of wit, in which a letter written to diuers play-makers, is offensively by one or two of them taken, and because on the dead they cannot be auenged, they wilfully forge in their concietes a liuing Author: and after tossing it two and fro, no remedy, but it must light on me. How I haue all the time of my conuersing in printing hindred the bitter inueying against schollers, it hath been very well knowne, and how in that I dealt I can sufficiently prooue. With neither of them that take offence was I acquainted, and with one of them I care not if I neuer be: The other, whome at that time I did not so much spare, as since I wish I had, for that as I haue moderated the heate of liuing writers, and might haue vsde my owne discretion, (especially in such a case) the Author beeing dead, that I did not, I am as very, as if the originall fault had beene my fault, because my selfe haue scene his demeanor no lesse ciuill than he exclent in the qualitie he professes

With this very public apology & refutation of Greene’s attack, Shakespeare, it seems, had become the darling of the London’s Theatre world. There would be no looking back!

The Young Shakespeare (14): Ireland, Scotland & Denmark

1588-89

Winter

Shakespeare Influenced by John Lyly

By the winter of 1588, Shakespeare was heavily into writing the Elizabethan equivalent of romcoms. Since his return from the continent he had already created LLL, Twelfth Night &The Taming of the Shrew, all of which share familial affinities in common. When writing his next play, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Shakespeare went to the playhouse to see John Lyly’s Midas sometime between late 1588 & early 1589. When he came to writing Two Gentleman, Shakespeare would transplant the essence of a couple of Lyly’s scenes into his new play, such as the discussion between Launce and Speed regarding the vices and virtues of Launce’s mistress. Two Gentlemen may have been started on the Grand Tour; for Honigmann gives it a date of 1587, reasoning, ‘in terms of basic dramatic technique the play is more naive than anything else in the canon.’

The next play admitted to Shakespeare’s merry gang of jaunty comedies was The Merry Wives of Windsor, seems to have been penned over the winter of 1588-89. One of the songs in the play can be connected to Lyly.

Fie on sinful fantasy!

Fie on lust and luxury!

Lust is but a bloody fire,

Kindled with unchaste desire,

Fed in heart, whose flames aspire

As thoughts do blow them, higher and higher.

Pinch him, fairies, mutually;

Pinch him for his villany;

Pinch him, and burn him, and turn him about,

Till candles and starlight and moonshine be out.

These lyrics are lifted from from the Fairy Song in Endymion, a play by Lyly, the manager of the St Paul’s Boys. Endymion was first published in 1591, but a statement on the quarto title page stating ‘played before the Queens Majestie on Candlemas Day’ could only refer to a performance in 1588. Candlemass is the 2nd of February, & the only record of a Candlemass payment to the St Paul’s Boys was in 1588.

In III-1, the song sung by Hugh Evans beginning…

To shallow rivers, to whose falls

Melodious birds sings madrigals;

There will we make our beds of roses,

And a thousand fragrant posies.

…is a clear remould of Marlowe’s famous song;

COME live with me and be my Love,

And we will all the pleasures prove

That hills and valleys, dale and field,

And all the craggy mountains yield.

There will we sit upon the rocks

And see the shepherds feed their flocks,

By shallow rivers, to whose falls

Melodious birds sing madrigals.

There will I make thee beds of roses

And a thousand fragrant posies,

A cap of flowers, and a kirtle

Embroider’d all with leaves of myrtle.

1589

SPRING

Shakespeare joins the Queen’s Players

‘The parallels between Shakespeare’s plays & the Queen’s plays,’ writes Terence G Schoone-Jongen, ‘are substantial & intricate.’ That Shakespeare was a member of the Queen’s Players seems likely. During 1588 & 1589, the Derby Household Book shows that the Queen’s Men visited Latham & Knoswley five times, bringing them into the immediate Stanley circle. A number of their recorded plays would be rewritten by Shakespeare, with lines & phrases from the Ur-types popping all across his extensive ouevre. Where the Queen’s Players produced Richard III & King Leir, so Shakespeare wrote a version of Richard III & the spell’d slightly differently, King Lear. Elsewhere, The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth forms the entire foundation for the material of 1 Henry IV, 2 Henry IV and Henry V, while their Troublesome Reign of King John is simply a redaction of Shakespeare’s King John. So much so, that in the 1611 quarto printing of the Troublesome Reign, the authorship was assigned to ‘W. Sh’ which was elongated in the 1622 printing into ‘W. Shakespeare.’

Among the many similarities which have been observ’d, Launce’s rebuking of his dog, Crab, in Two Gentlemen, finds a precedent in Sir Clyomon & Sir Clamydes. That same play also bears a strong resemblance to the mechanicals of the playlet in Act V of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Regarding the two Lears, Sir Walter Greg suggested that, ‘ideas, phrases, cadences from the old play still floated in his memory below the level of conscious thought, &… now & again one or another helped to fashion the words that flowed from his pen.’ Elsewhere, Brian Walsh remarks on Shakespeare’s acute familiarity with the ‘recitation of genealogy from plays in the Queen’s Men repertory,’ & also observes how Shakespeare’s King John keeps the line, ‘For that my grandsire was an Englishman,’ & the two Hamlets share, ‘the screeking Raven sits croking for revenge.’

Shakespeare’s entry into the Queen’s might be related to the absence from the troupe of that most famous of Elizabethan actors, & Queen’s Man, Richard Tarleton. He had died in September 1588 & the Men would have been in need of fresh blood – & who better than the brilliant Young Shakespeare to step into the role. Incidentally, Tarleton was a West Midlands lad just like Shakespeare, a remembrance to whom is contained thro the Hamlet’s court jester, to whose skull is spoken the ever famous line, ‘alas poor Yorick, I knew him so well. Coincidence or not, a certain trustee of Tarleton’s will, William Johnson, would one day become a trustee on Shakespeare’s purchase of a house in Blackfriars.

Shakespeare’s presence association with the Queen’s Men immediately affected his writing, for in Two Gentlemen we see an affiliation with the (now lost) with the Queen’s Players’ Felix & Philomena, which the Revels Accounts record as being perform’d for the court at Greenwich Palace on 3 January 1585. This was based on Spanish prose romance Los Siete Libros de la Diana (The Seven Books of the Diana) by the Portuguese writer Jorge de Montemayor, where the story of Don Felix and Philomena is told. Shakespeare might even have had a familiarity with Diana from his time in Spain- an English translation was not available until Bartholomew Young published his in 1598 – & it cannot be denied that Two Gentlemen has a definite sprinkle of Don Quixote.

1589

SUMMER

Shakespeare gets involved with the Blackfriars Theatre

All through his life Shakespeare would be involved in every aspect of the stage, taking part-shares in theatres, writing the plays, & even bloody acting in them. He was a veritable Mister.Theatre. His first venture into the financial side of things was in 1589, when he took a share in the Blackfriars Theatre. Evidence for this comes through a manuscript which had passed into the hands of Lord Ellesmere, the then attorney-general, in the 1840s. The manuscript reveals how Shakespeare’s name stands twelfth in the enumeration of the members of the company;

These are to certifie your right Honble Lordships, that her majesty’s poore playeres, James Burbadge, Richard Burbadge, John Laneham, Thomas Greene, Robert Wilson, John Taylor, Anth. Wadeson, Thomas Pope, George Peele, Augustine Phillipps, Nicholas Towley, William Shakespeare, William Kempe, William Johnson, Baptiste Goodale, & Robert Armyn, being all of them sharers in the black Fryers playehouse, have never given cause of displeasure, in that they have brought into their playes maters of state & Religion, unfitt to be handled by them, or to be presentved before lewde spectators: neither hath anie complaynte in that kinde ever bene preferrd against them, or anie of them. Wherefore, they trust most humblie in your Lordships consideration of their former good behaviour, being at all tymes readie, & willing, to yeelde obedience to any command whatsoever your Lordships in your wisdome may thinke in such case meete, &c.

About this time we also have a possible attack on Shakespeare by Thomas Nashe, who in the Preface to Robert Greene’s Menaphon – a prose romance with interludes of verse published in 1589 – writes quite bitterly;

But herein I cannot so fully bequeath them to folly as their idiot art-masters, that intrude themselves to our ears as the alchemists of eloquence, who (mounted on the stage of arrogance) think to outbrave better pens with the swelling bombast of bragging blank verse.

1589

SUMMER

Shakespeare Reads Out Venus & Adonis

One hot summer’s day in London, 1589, perhaps on the lawn of Fisher’s Folly, Shakespeare was reading Venus & Adonis to a select crowd. He was 25 – a fun-loving age if ever there was one – & to have been in attendance at a drunken evening filled with the early stanzas of Shakespeare’s erotic masterpiece would have been great fun. One man that felt the poem more than most was Thomas Lodge, whose 1589 poem ‘Scillaes Metamorphosis,’ has many captivating echoes of V&A. Lodge also spent time in the Earl of Derby’s household in the 1580s, which ensures his admission into the private circle about Stanley & Shakespeare. As for his ‘Scillaes Metamorphosis, Shakespeare’s words are taken almost wholesale;

But like a stormy day, now wind, now rain,

Sighs dry her cheeks V&A

And when my tears had ceas’d their stormy shower

He dried my cheeks Lodge

Sometimes she shakes her head, and then his hand,

Sometime her arms infold him like a band V&A

Some chafe his temples with their lovely hands,

Some weep, some wake, some curse affection’s bands Lodge

Lodge’s poem uses the same 6-lined stanza & rhyme scheme of Venus & Adonis, & even pays tribute to Shakespeare’s master-class with the following stanzas;

He that hath seen the sweet Arcadian boy

Wiping the purple from his forced wound,

His pretty tears betokening his annoy,

His sighs, his cries, his falling on the ground,

The echoes ringing from the rocks his fall,

The trees with tears reporting of his thrall:

And Venus starting at her love-mate’s cry,

Forcing her birds to haste her chariot on;

And full of grief at last with piteous eye

Seeing where all pale with death he lay alone,

Whose beauty quail’d, as wont the lilies droop

When wasteful winter winds do make them stoop:

Her dainty hand address’d to daw her dear,

Her roseal lip allied to his pale cheek,

Her sighs, and then her looks and heavy cheer,

Her bitter threats, and then her passions meek;

How on his senseless corpse she lay a-crying,

As if the boy were then but new a-dying.

1589

AUGUST-SEPTEMBER

Shakespeare Visits Ireland

Since their formation in 1583, the Queen’s Players had been the leading troupe of actors in the land, travelling widely, with prominent performances at court over the prestigious festive seasons. Shakespeare joined the Queen’s Players at a time when they were dividing themselves into sub-troupes. ‘By 1589,’ writes Terence G Schoone-Jongen, ‘each branch – one apparently led by John & Laurence Dutton, the other by John Laneham – was sometimes identified by its leader as well as patron. Initially, the divided branches may have been a touring practice.’

Through Shakespeare’s presence among the Queen’s Players, we can now place him in Ireland. Shakespeare. An entry in the Ancient Treasury Book of Dublin reveals that in 1589, four pounds was paid to troupes called The Queen’s Players and The Queen and Earl of Essex Players ‘for showing their sports.’ These two troupes then travel over the Irish Sea to Lancashire, where at Knowsley the Queen’s Men performed in the evening of 6th Sept. and in the afternoon of 7th Sept., and then Essex’s Players performed in the evening of 7th Sept.

While in Ireland Shakespeare would have heard the word, Púca, which means ghost & went on to become ‘Puck’, the name of a ‘spirit’ in Midsummer Nights Dream (Act II Scene 1). He might have also heard phrases like “A hundred thousand welcomes” – Coriolanus (Act II Scene I) & “Did you ever hear the like?…….Did you ever dream of such a thing?” (Pericles Act IV Scene IV 1). The Irish were & still are world renownwed for the music, & famous. The phrase “Calin o custure me” in Henry V is taken from an Old Irish harp melody called “Cailín ó cois Stúir mé”;

When as I view your comely grace

Caleno custurame

Your golden hairs, your angel’s face,

Caleno custurame

W.H. Gratton Flood in his ‘History of Irish Music’ devotes a whole chapter to Shakespeare’s knowledge of 11 Irish songs, being;

1. Callino casturame – Mentioned as an Irish tune in ‘A handful of Pleasant dities’ (1594).

2. Ducdame – a corruption of An d-tiocfaidh from Eileen A Rún .

3. “Fortune my Foe” – (Merry Wives of Windsor Act II Scene III) ‘reckoned always an Irish tune’.

4. “Peg a Ramsay” – (Twelfth Night Act II Scene III) A ‘dump tune’ which Flood states were played on a small Irish harp called a tiompán

5. “Bonny Sweet Robin”

6. “Whoop do me no harm, good man”- (A Winter’s Tale Act IV Scene III) known in Ireland as “Paddy whack.”

7. “Welladay; or Essex’s last Good-Night” – about the death of the Earl of Essex in Ireland in 1576.

8. “The Fading ” or “Witha a fading” – (“A Winter’s Tale” Act IV) “is, even on the testimony of the late Mr William Chappell (an uncompromising advocate of English music) undoubtedly an Irish dance tune. Also called the ‘Rince Fada’.”

9. “Light o’ Love” – (Two Gentlemen of Verona Act I Scene 2) an allusion is made to the tune of ‘light o’love’ another Irish tune.

10. “Yellow Stockings” – Known in Gaelic as “Cuma, liom” and the reference is to the saffron ‘truis’ of the medieval Irish.

11. “Edgar: Wantest thou eyes at trial, madam ? Come o’er the bourn, Bessie, to me.” – (King Lear Act III Scene VI)

1589

SEPTEMBER

The Queen’s Players are sent to the court of King James

King James VI of Scotland clearly loved the theatre, surrounded himself with artists and musicians, collectively known as the Castalian Band. He even composed many decent enough poems of his own. To help celebrate his upcoming marriage to a princess of Denmark called Anna, he asked Queen Elizabeth of England if he could borrow some of her actors, & it is Her Majesty’s granting of her royal cousin’s request that commences Shakespeare’s first visit to Scotland. The statement of the Revels tells us in that in September 1589 money was paid; ‘ for the furnishing of a mask for six maskers and six torchbearers, and of such persons as were to utter speeches at the shewing of the same maske, sent into Scotland to the King of Scotts mariage, by her Majestieís commanundement.’ Among the ‘six maskers,’ we shall place William Shakespeare, now a fully-fledg’d member of one of the half-troupes into which the Queen’s Players were dividing in 1589.

After the request had reached Knowsley, & after their last performance there on the afternoon of the 7th, it seems that it took the Queen’s Players three days to travel the 100 miles or so between Knowsley & Carlisle by the 10th September. The governor of Carlisle, Baron Scroop of Bolton, soon found himself involv’d in this high proflie case of pass the parcel, writing;

After my verie hartie comendacions: vpon a letter receyved from Mr. Roger Asheton, signifying vnto me that yt was the kinges earnest desire for to have her Majesties players for to repayer into Scotland to his grace : I dyd furthwith dispatche a servant of my owen unto them wheir they were in the furthest part of Langkeshire, wherevpon they made their returne heather to Carliell, wher they are, and have stayed for the space of ten dayes, whereof I thought good to gyve yow notice in the respect of the great desyre that the king had to have the same Come unto his grace: And withall to praye yow to gyve knowledg therof to his Majestie. So for the present, I bydd yow right hartelie farewell

Carlisle

The xxth of Septemre, 1589

Yowr verie assured loving friend

H Scrope

What Shakesepeare got up to in those 10 days in Cumbria we do not know – there are no traces of the county in his works. One expects they were rehearsing hard for the forthcoming nuptials, & maybe a little carousing with the locals. Its a nice city.

1589

OCTOBER

Shakespeare in Scotland

As storms raged across the North Sea, Princess Anna of Denmark was unable to make the treacherous crossing, leading to James camping up at Seton Castle to watch the Firth of Forth for her ship. A letter from William Asheby to Walsingham. [Sept. 8, 1589) reads;

With the first wind the Queen is expected out of Denmark. It is thought that she embarked about the 2nd instant, but that contrary winds keep the fleet back. Great preparation is made at Leith to receive her, and to lodge her till the solemnity, which shall be twelve days after her arrival. The King is at Seaton till her arrival.

A week later, William Asheby wrote;

We dailie now expect the fleet of De[nmark]. The Quene embarqued at Copmanhaven [on] Moundaie the first of this moneth, and [hath] not set foote on ground sithence, except [the] last storme, which continued the 12 and thirten of this present southwest, haith driven the fleet back into Norwaie, [as] in all likliehode it haith done.

The Lord Dingwall arrived here this [day]. He left the Quene and the whole fleet on [this] side of Elsenoure, and had sight of the same nere the Skaw. It is certen[ly] looked that the Quene shall arrive in this Firth within as shorte space as [wind] and wether cane serve from Norwaie [to] this cost, which maie be in foure or fi[ve] daies, if thei have keapt the seas, and not entred over farr the Sound of .

The wind haith ben southwest and gre[at] this foure daies last past. This daie it groweth calmer and northwest, so as in . . . daies the Quenes arrivall is expected at Le[ith], where great preparacion is made to receave her.

The wait dragg’d on & on & a very impatient & romantically-minded James, ‘passionate as true lovers be’, was on the 8th of October said to ‘lyeth at Cragmillar, hard by Edenbrowghe, retyred, and as a kind lover spends the t[yme] in sighing.’ His malaise was soon converted to action & he decided that instead of waiting he would risk the crossing & marry his young bride in Norway instead. Bring the mountain to Mohammed.

With him went Shakespeare, but before they sailed from Leith on October 24th, Shakespeare clearly spent time perusing the Royal Library in Edinburgh. In 1589 it held the single, 43,000 lines-long manuscript copy of William Stewart’s Chronicle of Scotland. Written in the Scottish vernacular, there are positive parralels with Macbeth, including one of sixty-five lines which elucidates the murderous motives of Macbeth and his wife. Wilson notes that, ‘Boece and Holinshed have nothing corresponding to this, and yet how well it sums up the pity of Macbeth’s fall as Shakespeare represents it.’ Another chronicle-marker is the 26-line tirade by Lady Macbeth as she taunts her husband as being a coward and unmanly and breaking his vow to seek the crown (1.7.36–61). ‘In every case in which Stewart differs from Holinshed,’ says Stopes, ‘Shakespeare follows Stewart.’

Other sources for Macbeth which Shakespeare would have studied in the Royal Scottish Library include Andrew Wyntoun’s metrical ‘Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland’ & also the ‘Flyting betwixt Montgomerie and Polwart,’ a poem which contains the three wyrd sisters. In the latter text After their bewitching curses come to a close, they begin to speak to each in turn, just as they deliver their prophecies in Macbeth.

The first said, ‘surelie of a shot;’

The second, ‘of a running knot;’

The third, ‘be throwing of the throate,

Like a tyke ouer a tree (Flyting)

When shall we three meet again

In thunder, lightning, or in rain?

When the hurlyburly’s done,

When the battle’s lost and won.

Fair is foul, and foul is fair:

Hover through the fog and filthy air (Macbeth)

We also have two allusions are to Scots law: “double trust” and “interdiction.” the Oxfordian Richard F. Whalen explains it all quite succinctly’

Macbeth says of Duncan: “He’s here in double trust: First, as I am his kinsman and his subject, strong both against the deed; then as his host, who should against his murderer shut the door, not bear the knife myself” The “double trust” concept was enacted into law in 1587 when the Scottish Parliament raised from mere homicide to treason the slaying of someone of rank who was also a guest of his slayer, with the trial to be held in the highest court.

The legal term “interdiction” occurs in the strange colloquy between Macduff and Malcolm. Macduff laments that Malcolm, the heir to the throne, “by his own interdiction stands accused and does blaspheme his breed” This refers in Scots law to someone conscious of his failings who gives up or is forced to give up the management of his own affairs, which is what Malcolm seemed to be doing, much to Macduff’s dismay.

The thing about Oxfordians is that they are the most meticulous researchers – they turn over stone several times & check for how it looks for the light, & their research has been invaluable to tell you the truth – team work!

One of the most important pieces of local knowledge embedded in the play is that of Macbeth’s armour-bearer being named Seton. The legends of Macbeth do not mention any Setons, but Professor Wilson of the University of Edinburgh was astonish’d that “somehow or other” Shakespeare learned that the Setons were the hereditary armour-bearers to the kings of Scotland. But of course Shakespeare was on the very Seton spot with King James.

Finally, the date of Shakespeare’s visit to Macbeth country is intriguing, as the plays spirit seems to have fused with a contemporary event – the murder of the Duke of Guise by Henry III of France in December 1588. Eva Turner Clark, in her ‘Hidden Allusions in Shakespeare’s Plays ‘(1931), observed ‘many points in common’ between the Killing of Duncan by Macbeth and the murder of Guise by Henry III, citing ‘the power and influence’ of Catherine De’ Medici, who was inside the Chateau of Blois in France when the murder took place, just as Lady Macbeth is in Macbeth’s Castle in Scotland during the murder of Duncan.

1589

OCTOBER

Shakespeare sails to Norway

That Shakespeare & the Queen’s Players went with King James in his large wedding entourage can be discerned through an epigram in John Davies of Hereford’s The Scourge of Folly (c.1610). Dedicated to, ‘our English Terence Mr. Will: Shake-speare,’ it begins;

SOME say good Will (which I, in sport, do sing)

Had’st thou not plaid some Kingly parts in sport,

Thou hadst bin a companion for a King

Scholars have scratched their heads over this passage for centuries, but there is a starkness to it which fits with consummate ease into the Queen’s Player’s accompanying of King James VI to Denmark.

So Shakespeare & James had set off for Norway, with the king’s the journey being described thus;

He was more than fortunate than his bride in having four days of fair weather, but on the fifth a storm arose & a day later he landed at Flekkefjord in Norway.

It must have been quite a poetic moment for our young bard, leaving him verteux & receptive to the energies which would one day manifest themselves in Hamlet. From Flekkefjord Shakespeare & James proceeded to Oslo. In the Danish cccount of the day, translated by Peter Graves, we observe how Shakespeare fbecame acquainted with the figure who would be creochisped into ‘Hamlet’ as Guildenstern, the friend of Rosencrantz.

When his majesty arrived, he went to to Old Bishop’s palace to meet her ladyship. this was the order of the procession: first walked two Scottish noblemen (who were his majesty’s heralds) each bearing a white stick as a sign of peace; next came Steen Brahe, Henning Gioye, Axel Gyldenstierne, Hans Pederson, Ove Juel, Captain Noimand & Peter Iversen; then came his majesty between the Scottish earl & another Scottish lord; after them came the king’s courtiers & the Scottish nobility, all with their hats in their hands

As for Rosencrantz, he would have been about somewhere, for among the Danish signatories to the prenuptual demands made by Scottish enjoys on behalf of the King (9th July 1589), we can observe a certain ‘Jørgen Rozenkrantz.’

1589-90

WINTER

Shakespeare visits Kronborg Castle

James and Anne were married in Oslo, November 23rd, at the great hall in Christen Mule’s house with all the splendour possible at that time & place. As they drove from the church James arranged a curious spectacle for the entertainment of the people of Oslo. By his orders four young “blackamoors” danced naked in the snow in front of the royal carriage, but the cold was so intense that they died a little later of pneumonia. After the nuptials, most of the entourage returned to Scotland, but others – including the Queen’s Players – accompanied the royal couple to Kronborg Castle in Denmark. It must be noted that while this half of the Queen’s Players were in Denmark, the others were performing over the festive season for Queen Elizabeth, where for a performance at Richmond court on the 26th December, they receiv’d the princely sum of £20.

The King was in a great mood, & wrote home that, ‘we are drinking & dryving (killing time) in the auld manner.’ Kronborg is the very place in which Hamlet as we know it was set, yet the original story, as given by Saxo Grammaticus, shows how Hamlet’s father was the governor of Jutland. Kronborg, however, is on Zealand. Then why did Shakespeare move the scene?

We may now assume that on his visit to Denmark, Shakespeare began to revise his Hamlet, adding genuine on-the-spot location stuff to an earlier version of the play. Shakespeare’s presence at Kronborg as part of a wandering troupe of players echoes out into Hamlet’s famous ‘play-within-the-play,’ where a troupe of traveling players enact a ‘Dumb-Show’ call’d the Murder of Gonzaga (or the Mousetrap).

Enter a King and a Queen, very lovingly: the Queen embracing him, and he her. She kneels and makes show of protestation unto him. He takes her up, and declines his head upon her neck: lays him down upon a bank of flowers: she, seeing him asleep, leaves him. Anon comes in a fellow, takes off his crown, kisses it, and pours poison in the Kingís ears, and exit. The Queen returns; finds the King dead, and makes passionate action. The Poisoner, with some two or three Mutes, comes in again, seeming to lament with her. The dead body is carried away. The Poisoner wooes the Queen with gifts; she seems loath and unwilling awhile, but in the end accepts his love.

There is a definitive nod to James in Shakespeare’s play. Just as Hamlet’s father is the King in the Dumb-Show was murdered by having poison administered to his ear, a French surgeon, Ambrosie Parex, was suspected of killing the French King, Francis II, by giving him an ear infection during the course of treatment. Francis was the first husband of James’ mother, Mary Queen of Scots. That the Gonzaga family heralded from Mantua, & of course we have already placed Shakespeare in that city with Stanley.

1590

SPRING

Shakespeare returns to Scotland

In early 1590, James returned to Scotland with his new wife. That Shakespeare was back in Scotland in wintry months is reflected by his uncanny observation in Macbeth of “so fair and foul a day I have not seen.” During the coronation ceremonies in Edinburgh, the masque ordered by James the previous September finally got its chance to be aired. Although Shakespeare is not mentioned by name, the clothes he & his five other masquers are, as given in Lansd.MSS 59.

A maske of six coates of purple gold tinsell, garded with purple & black clothe of silver striped. Bases of crimson clothe of gold, with pendants of maled purple silver tinsell. Twoe paire of sleves to the same of red cloth of gold, & four paire of sleves to the same of white clothe of copper, silvered. Six partletts of purplee clothe of silver knotted/ Six hed peces, whereof foure of clothe of gold, knotted, & twoe of purple clothe of gold braunched. Six fethers to the same hed peces. Six mantles, whereof four of oringe clothe of gold braunched, & twoe of purple & white clot of silver braunched. Six vizardes, & siz fawchins guilded.

Six cassocks for torche bearers of damaske; three of yellowe, & three of red, garded with red & yellow damaske counterchaunged. Six paire of hose of damaske; three of yellow, & three of red, garded with red & yellowe damaske counterchaunged. Six hatts of crimson clothe of gold, & six fethers to the same. Six vizardes.

Four heares of silke, & four garlandes of flowers, for the attire of them that are to utter certaine speeches at the shewing of the same maske.

The masque may have been part of the luscious celebrations made during the procession up the Royal Mile made by the new queen, or perhaps performed at the festivities in Edinburgh castle. That Shakespeare was under the Stuart wing at this time seems to reflect itself into Macbeth again, in particular the 1590 witch trials of Denmark & North Berwick, near Edinburgh. The poor ‘witches’ had been given the blame for the bad weather keeping Anna from James, & also the terrible storms they had to endure on the return voyage. No-one dared to mention that winter might have had something to do with it, & more than a hundred suspected witches in North Berwick were arrested. Many would soon be confessing – under torture of course – to having met with the Devil in the church at night, and devoted themselves to doing evil, including poisoning the King and other members of his household, and attempting to sink the King’s ship. When writing Macbeth, Shakespeare would adapt many concepts from the trials, including the rituals confessed by the witches & the borrowing of quotes from the treaties, such as spells, ‘purposely to be cassin into the sea to raise winds for destruction of ships.’

There are in Macbeth quite canny descriptions of Scottish weather, when ‘so fair and foul a day I have not seen.’ Shakespeare also describes how the, ‘air nimbly and sweetly recommends itself unto our gentle senses‘ to which Banquo adds ‘Heaven’s breath smells wooingly here. The air is delicate,’ Is this a remembrance in Shakespeare of visiting some Highland scene, especially the castle of Macbeth, described by Shakespeare as a ‘pleasant seat.’ Arthur Clark also notes that Inverness has an unusually mild “microclimate” distinct from the rest of Scotland, and he too wonders how Shakespeare could have known about it without having visited Inverness. Clark also shows how Shakespeare accuraelty locates Dunsinane, Great Birnam Wood, Forres, Inverness, the Western Isles, Colmekill, Saint Colme, and the lands that gave their names to the thanes: Fife, Glamis, Cawdor, Ross, Lennox, Mentieth, Angus and Caithness. Again, on the spot knowledge seems likely, while in Banquo’s question: “How far is it called to Forres”? the use of the word “Called,” reflects a typical Scots locution of the time.

1590

SPRING

Shakespeare & the Arte Of English Poesie

It was in late 1588 that Shakespeare began to convert all the materials he collected, & all the observations he made whilst travelling, into theatrical gold dust. He may have had a mind burgeoning with ideas, even a few rough sketches of scenes & storylines, & a number of drafted passages of poetic speech. What the needed now was focus, & perhaps he had conversed with the anonymously printed Arte of English Poesie was entered at Stationers’ Hall in 1588. WL Rushton has identified over 200 literary links between the Puttenham’s Arte & the works of Shakespeare, showing how the bard must have read it. Shakespeare may even have read the work in manuscript, for there is one passage in particular that seems to be the Shakesperean manifesto;

There were also poets that wrote openly for the stage, I mean plays & interludes, to recreate the people with matters of disport, & to that intent did set forth in shows & pagaents common behaviours & manner of life as were the meaner sort of men, & they were called comical poets, of whom among the greeks Meander & Aristophanes were most excellent, with the Latins Terence & Plautus. Besides those poets comic there were others, but meddled not with so base matters: for they set forth doleful falls of unfortunate & afflicted princes, & were called poets tragical. Such were euripedes among the others who mounted nothing so high as any of them both, but in based & humble style, by manner of dialogue, uttered the private & familar talk of the meanest sort of men, as shepherds, haywards & such like

Authorship of the book has been associated with George Puttenham, but there is a possibility it was penn’d by Shakespeare himself. The book was was printed by Richard Field, Shakespeare’s Stratford countryman in London, on which title page was exhibited the same title Emblem “Anchor of Hope”, as found on “Venus and Adonis”(1593) and “Lucrece”(1594). In 1909, William Lowes Rushton published a book, “Shakespeare and ‘The Arte of English Poesie’ ”, in which he shows that Shakespeare used a number of figures which the author of “The Arte.…” describes, & also extensively uses similar words and phrases found in the book in his own plays. For example, Zurcher tells us, ‘Shakespeare would make Puttenham’s final three chapters from the Arte of English Poesie the basis of his analysis of artificiality, sincerity & power in the contest between Brutus & Mark Anthony In Julius Ceasar.’ The authorship debate is ongoing, but what is clear is that Shakespeare & the book are intrinsically connected.

The Young Shakespeare (13): Christmas With the Stanleys 1588-89

In 1588 Shakespeare joined the Stanley family at Knowsley for a very special festive season. Ferdinando Stanley was becoming a very important figure in English theatre When the Earl of Leicester died on the 4th September, 1588, his theatrical troupe merged with Ferdinando’s Lord Strange’s Men. This infusion of lifeblood really helped ressurrect the company, which had not done anything for years. Both the Theatre & the Curtain playhouses in London were then used by the company in 1588 & 1589, which brings them into the Shakespearean orbit.

The Stanleys were Oxford University boys, & would had grown up with the long-standing tradition of plays being acted out over the festive season. MJ Davis writes, ‘Christ Church & St Johns were the two colleges where drama flourished most. At Christ Church there was a decree that two comedies & two tragedies – one of each in Greek &, the others in Latin – were to be acted during the Christmas season each year. Whereas Cambridge excelled in comedy, Oxford excelled in tragedy, with Seneca’s plays prominent towards the end of Elizabeth’s reign.’ In the same fashion, over the Festive season of 1588-89, two different plays were acted to a great pantheon of northern dignitaries. The Household Accounts book describe the events of the theatrical festive seasons;

29 December 1588 – 4th January 1589

Sondaye Mr Carter pretched at which was dyvers strandgers, on mondaye came mr stewarde, on Tuesday the reste of my lords cownsell & also Sir Ihon Savadge, at nyghte a play was had in the halle & the same nyght my Lord strandge came home, on wednesdaye mr fletewod pretched, & the same daye yonge mr halsall & his wiffe came on thursedaye mr Irelande of the hutte, on frydaye Sir Ihon savadge departed & the same daie mr hesketh mr anderton & mr asheton came & also my lord bushoppe & sir Ihon byron

This tells us that ‘a play was had in the halle’ on New Years Eve, on the very same night ‘Lord strandge came home.’ When Four days later Thomas Hesketh also arrives at Lathom, we get the idea that Shakespeare was also in the vicinity. The play would have been performed in the Derby’s private theatre at Knowsley, which survived until 1902 as ‘Flatiron House.’ It had been built on the waste by Richard Harrington, a tennant of Prescot Hall, of which place Richard Wilson writes, ‘the Elizabethan playhouse at Knowsley, near Liverpool, remains one of the dark secrets of Shakesperian England. Very few commentators are aware of even the existence of this theatre, built by the Stewards of Henry Stanley, Earl of Derby, on the site of his cockpit, some time in the 1580s.’ Other visitors that Christmas include some of the most important men in the north of England, such as the Bishop of Chester, William Chanderton & Sir John Byron, an ancestor of the poet Lord Byron. It is clear that they came to see a play, for the next entry in the household book reads;

5th January to 10th January

sondaye mr caldwell pretched, & that nyght plaiers plaied, mondaye my Lord bushop pretched, & the same daye mr trafforth mr Edward stanley, mr mydleton of Leighton came on Tuesdaye Sir Richard shirbon mr stewarde my Lord bushoppe Sir Ihon byron & many others departed, wednesdaye my lord removed to new parke, on frydaye mr norres & mr tarbocke & mr Tildesley came & went

The key information here is that a second play was performed on the evening of 5th January – a time known to the Church of England as ‘Twelfth Night.’ A similar timed performance was played at court & recorded as, ‘1583. Jan. 5. A mask of iiadies on Twelfth Eve.’ Looking at the Shakespearean ouevre, it makes sense that his early-feeling Twelfth Night was played on this occasion. Samuel Pepys recorded on January 6th, 1662; ‘Dinner to the Duke’s house, & there saw ‘Twelfth-Night’ acted well, though it be but a silly play, & not related at all to the name or day.’

There is a notice of a lost play by Shakespeare, whose sole mention comes in the 1598 Palladis Tamia, Wits Treasury, by Francis Meres. The passage basically tells us what Shakespeare had produced by that time;

As the soul of Euphorbus was thought to live in Pythagoras, so the sweet witty soul of Ovid lives in mellifluous and honey-tongued Shakespeare, witness his Venus and Adonis, his Lucrece his sugared Sonnets among his private friends…. As Plautus and Seneca are accounted the best for Comedy and Tragedy among the Latins, so Shakespeare among the English is the most excellent in both kinds for the stage…. for Comedy, witness his Gentlemen of Verona, his Errors, his Love Labours Lost, his Love Labours Won, his Midsummer Night’s Dream, and his Merchant of Venice; for Tragedy his Richard the 2, Richard the 3, Henry the 4, King John, Titus Andronicus, and Romeo and Juliet.

The presence of Loves Labour Lost right next to Loves Labours Won suggest that they were originally played in sequence, which fits in perfectly with the festivities at Knowsley. Loves Labours Lost would have been performed at Christmas, with Love’s Labours Won/Twelfth Night being performed on the evening of January 5th. Stylistically & linguistically, the frantic energetic comedy of Love’s Labours Won/Twelfth Night resembles the Comedy of Errors, which we have dated to 1588.

In 1602 we have the first ‘official’ record of a performance of Twelfth Night, in John Mannigham’s ‘Diary,’ when we hear’ ‘Feb. 2.–At our feast wee had a play called ‘Twelve Night, or What you Will,’ much like the Commedy of Errores, or Menechmi in Plautus, but most like and neere to that in Italian called Inganni. A good practise in it to make the steward beleeue his Lady widdowe was in love with him, by counterfayting a lettre as from his Lady in generall termes, telling him what shee liked best in him, and prescribing his gesture in smiling, his apparraile, etc., and then when he came to practise making him beleeue they tooke him to be mad.’ Most scholars presume this to be the first performance of Twelfth Night – but I would like to propose that it was first played twelve years earlier at Lathom. Both performances come in the middle of Leap Years, which connects to the play’s reference to the woman-in-charge Leap Year rule;

Praise we may afford To any lady that subdues a lord

If we bounce our investigation off the Stanley-Shakespeare romance, Twelfth night is also full of sexually unusual pairings, a feast of homoerotic feelings erupting from its chief author & its muse, who seem mirrored in the absolute bonding between Antonio & Sebastian. There are many subtextual echoes of the sonnets in Twelfth Night, especially in its handling of the humiliation of rejected love. Interestingly, the romantic wool seems to have fallen from Antonio’s eyes, whose god seems now more of a ‘vile idol.’ Also important is an echo of the sonnets’ menage a Trois in the Orsino, his boy & his lady triangle.

Turning now to Loves Labours Lost, Alfred Harbage once wrote, ‘I think that this play is more likely than any other to suggest the avenues of investigation if there is ever to be a ‘breakthrough’ in our knowledge of Shakespeare’s theatrical beginnings.’ Another scholar, Harley Granville-Barker, adds, ‘it abounds in jokes for the elect, were you not numbered among them you laughed, for safety, in the likeliest places. A year or two later the elect themselves might be hard put to it to remember what the joke was…. it’s a time-sensitive play for a very specific and select audience. Once we figure out who that audience is, we’ll know when the play was first written.’ When we observe there are a number of nods to the Stanleys throughout the play, surely we can answer Mr Harbage’s question. The play contains, for example, several references to the eagle; an important Stanley symbol as found on the family crest to the Eagle Tower at Latham.

What peremptory eagle-sighted eye

Dares looke upon the heaven of her brow

That is not blinded by her majestie

Earl Henry would loved to have heard about his beloved Navarre, the play’s setting, while Ferdinando would have been amused by his name being used as the main character. The Stanley household would have noticed that Malvolio was based upon steward, William Farrington. The play contains a masque – the Nine Worthies – identical to the one performed annually at nearby Chester. In a commentary on Love’s Labour’s Lost by Charles Knight, we read; ‘in this manuscript of… a Chester pageant… the Four Seasons concludes the representation of The Nine Worthies. Shakespeare must have seen such an exhibition, and have thence derived the songs of Ver and Hiems.’ This gives us a firm link to William Stanley, whose tutor, Richard Lloyd, wrote, ‘A brief discourse of the most renowned acts and right valiant conquests of those puissant Princes called the Nine Worthies.‘ Shakespeare must have seen Lloyd’s mask at some point in order to import the songs into his own play. Lefranc found many correspondences between Lloyd’s Nine Worthies and the masque in Love’s Labour’s Lost, and even reminiscent lines: In The Nine Worthies we read: ‘This puissant prince and conqueror bare in his shield a Lyon or, Wich sitting in a chaire bent a battel axe in his paw argent,‘ and in Love’s Labour’s Lost: ‘Your lion, that holds his poll-axe sitting on a close-stool, will be given to Ajax.’

With Shakespeare fresh from his Continental sonnetteering, it is no wonder that sonnets take an important cameo in the LLL. There is an extremely famous & charming sonnet-reading scene, which shows how much the art form was on Shakespeare’s mind at the time. Examples include;

So sweet a kiss the golden sun gives not

To those fresh morning drops upon the rose,

As thy eye-beams, when their fresh rays have smote

The night of dew that on my cheeks down flows:

Nor shines the silver moon one half so bright

Through the transparent bosom of the deep,

As doth thy face through tears of mine give light;

Thou shinest in every tear that I do weep:

No drop but as a coach doth carry thee;

So ridest thou triumphing in my woe.

Do but behold the tears that swell in me,

And they thy glory through my grief will show:

But do not love thyself; then thou wilt keep

My tears for glasses, and still make me weep.

Did not the heavenly rhetoric of thine eye,

‘Gainst whom the world cannot hold argument,

Persuade my heart to this false perjury?

Vows for thee broke deserve not punishment.

A woman I forswore; but I will prove,

Thou being a goddess, I forswore not thee:

My vow was earthly, thou a heavenly love;

Thy grace being gain’d cures all disgrace in me.

Vows are but breath, and breath a vapour is: