Samuel Johnson on Pope & Dryden

Dryden’s page is a natural field, rising into inequalities, and diversified by the varied exuberance of abundant vegetation; Pope’s is a velvet lawn, shaven by the scythe, and levelled by the roller.

As tradition ebbs & flows, so fashion comes & goes, & there can be no more of a fashion in English poetry than the more than a century long fastidious passion of the neo-classical couplet. Beginning in the mid seventeenth century & lasting all the way up to the dawn of the Romantics, of the poets who composed in the form there are two which may be considers as the true musical composers of the language. If Milton was a church organ, then Dryden & Pope were symphonies with strings. Pope’s reputation as a poet has always fluctuated. Some ages dote all over him, while others deny him even the title of a poet, as in Hazlitt’s;

The question, whether Pope was a poet, has hardly yet been settled, & is hardly worth settling; for if he was not a great poet, he must have been a great prose writer, that ism he was a great writer of some sort.

For me, Pope was a poet inhibited by poetical experience. Physically invalided, he never really travelled & his poetical creation was confined to books & his prodigious imagination. But a poet he has to be, his Iliad is the greatest transcreation in the English language, a real store house of my language’s phraseology, diction & vocabulary – a true epic lacking only its author’s original muse. Indeed, it was Dryden’s own work with the epic of Virgil that seems to have inspired Pope to his Iliadic task. Coleridge writes, in his Biographia Literia;

Of the two poets, & their differences, Samuel Johnson remarks with acute dissemination. The following passages come from his 1781 ‘Life of Pope,’ so obviously contains a slight bias to Pope, but it is in the comparison with Dryden that we gain such an accurate judgement of both men’s abilities.

In his perusal of the English poets he soon distinguished the versification of Dryden, which he considered as the model to be studied, and was impressed with such veneration for his instructer that he persuaded some friends to take him to the coffeehouse which Dryden frequented, and pleased himself with having seen him.

Dryden died May 1, 1701, some days before Pope was twelve: so early must he therefore have felt the power of harmony, and the zeal of genius. Who does not wish that Dryden could have known the value of the homage that was paid him, and foreseen the greatness of his young admirer?

Pope had now declared himself a poet; and, thinking himself entitled to poetical conversation, began at seventeen to frequent Will’s, a coffee-house on the north side of Russel-street in Covent-garden, where the wits of that time used to assemble, and where Dryden had, when he lived, been accustomed to preside.

He professed to have learned his poetry from Dryden, whom, whenever an opportunity was presented, he praised through his whole life with unvaried liberality; and perhaps his character may receive some illustration if he be compared with his master.

Integrity of understanding and nicety of discernment were not allotted in a less proportion to Dryden than to Pope. The rectitude of Dryden’s mind was sufficiently shewn by the dismission of his poetical prejudices, and the rejection of unnatural thoughts and rugged numbers. But Dryden never desired to apply all the judgement that he had. He wrote, and professed to write, merely for the people; and when he pleased others, he contented himself. He spent no time in struggles to rouse latent powers; he never attempted to make that better which was already good, nor often to mend what he must have known to be faulty. He wrote, as he tells us, with very little consideration; when occasion or necessity called upon him, he poured out what the present moment happened to supply, and, when once it had passed the press, ejected it from his mind; for when he had no pecuniary interest, he had no further solicitude.

His declaration that his care for his works ceased at their publication was not strictly true. His parental attention never abandoned them; what he found amiss in the first edition, he silently corrected in those that followed. He appears to have revised the Iliad, and freed it from some of its imperfections; and the Essay on Criticism received many improvements after its first appearance. It will seldom be found that he altered without adding clearness, elegance, or vigour. Pope had perhaps the judgement of Dryden; but Dryden certainly wanted the diligence of Pope.

In acquired knowledge the superiority must be allowed to Dryden, whose education was more scholastick, and who before he became an author had been allowed more time for study, with better means of information. His mind has a larger range, and he collects his images and illustrations from a more extensive circumference of science. Dryden knew more of man in his general nature, and Pope in his local manners. The notions of Dryden were formed by comprehensive speculation, and those of Pope by minute attention. There is more dignity in the knowledge of Dryden, and more certainty in that of Pope.

Poetry was not the sole praise of either, for both excelled likewise in prose; but Pope did not borrow his prose from his predecessor. The style of Dryden is capricious and varied, that of Pope is cautious and uniform; Dryden obeys the motions of his own mind, Pope constrains his mind to his own rules of composition. Dryden is sometimes vehement and rapid; Pope is always smooth, uniform, and gentle. Dryden’s page is a natural field, rising into inequalities, and diversified by the varied exuberance of abundant vegetation; Pope’s is a velvet lawn, shaven by the scythe, and levelled by the roller.

Of genius, that power which constitutes a poet; that quality without which judgement is cold and knowledge is inert; that energy which collects, combines, amplifies, and animates — the superiority must, with some hesitation, be allowed to Dryden. It is not to be inferred that of this poetical vigour Pope had only a little, because Dryden had more, for every other writer since Milton must give place to Pope; and even of Dryden it must be said that if he has brighter paragraphs, he has not better poems. Dryden’s performances were always hasty, either excited by some external occasion, or extorted by domestick necessity; he composed without consideration, and published without correction. What his mind could supply at call, or gather in one excursion, was all that he sought, and all that he gave. The dilatory caution of Pope enabled him to condense his sentiments, to multiply his images, and to accumulate all that study might produce, or chance might supply. If the flights of Dryden therefore are higher, Pope continues longer on the wing. If of Dryden’s fire the blaze is brighter, of Pope’s the heat is more regular and constant. Dryden often surpasses expectation, and Pope never falls below it. Dryden is read with frequent astonishment, and Pope with perpetual delight.

This parallel will, I hope, when it is well considered, be found just; and if the reader should suspect me, as I suspect myself, of some partial fondness for the memory of Dryden, let him not too hastily condemn me; for meditation and enquiry may, perhaps, shew him the reasonableness of my determination.

The chief help of Pope in this arduous undertaking {The Iliad} was drawn from the versions of Dryden. Virgil had borrowed much of his imagery from Homer, and part of the debt was now paid by his translator. Pope searched the pages of Dryden for happy combinations of heroick diction, but it will not be denied that he added much to what he found. He cultivated our language with so much diligence and art that he has left in his Homer a treasure of poetical elegances to posterity. His version may be said to have tuned the English tongue, for since its appearance no writer, however deficient in other powers, has wanted melody. Such a series of lines so elaborately corrected and so sweetly modulated took possession of the publick ear; the vulgar was enamoured of the poem, and the learned wondered at the translation.

Poetical expression includes sound as well as meaning. “Musick,” says Dryden, “is inarticulate poetry”; among the excellences of Pope, therefore, must be mentioned the melody of his metre. By perusing the works of Dryden he discovered the most perfect fabrick of English verse, and habituated himself to that only which he found the best; in consequence of which restraint his poetry has been censured as too uniformly musical, and as glutting the ear with unvaried sweetness. I suspect this objection to be the cant of those who judge by principles rather than perception; and who would even themselves have less pleasure in his works if he had tried to relieve attention by studied discords, or affected to break his lines and vary his pauses.

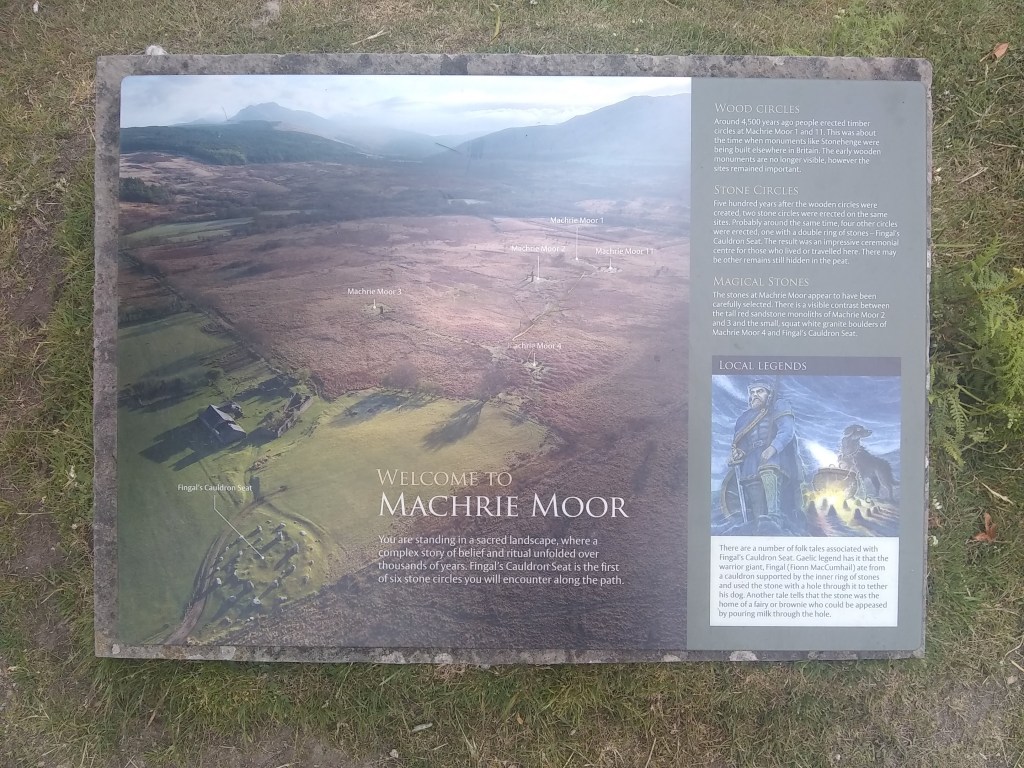

On The Antiquities of Arran (2): Machrie Moor, Stonehenge & the Worship of Saturn

Time has advanced my stay on Arran by a few weeks now, leading to me leaving my job at the hotel & in a few days opening the island’s first second hand bookstore in many years. A suitable base for a poet to have his office, close to both the opening of Glen Rosa & the sea, I hope to lead a fulfilling expedition into the antiquities of Arran. It will be called NINE BEES BOOKS, with the nine bees standing for ‘Burnley boy Bullen’s braw banter, butties, brews, browsing & …’ I think I might check ‘booyakasha’ in there somewhere. The butties & brews reference alludes to my wanting to sell proper ground coffee & open a spinach & sandwich bar.

As for my previous employment, I left the hotel after an incident. To cut a long story short, if you dont sub your breakfast chef a bottle of wine til morning, he won’t be making breakfast. That’s an old Burnley proverb, that is. But its also given me the freedom to be true to myself – a poet should be working on poems in the morning, not poached eggs. Then history in the afternoon, where I have made an important early breakthrough, I believe.

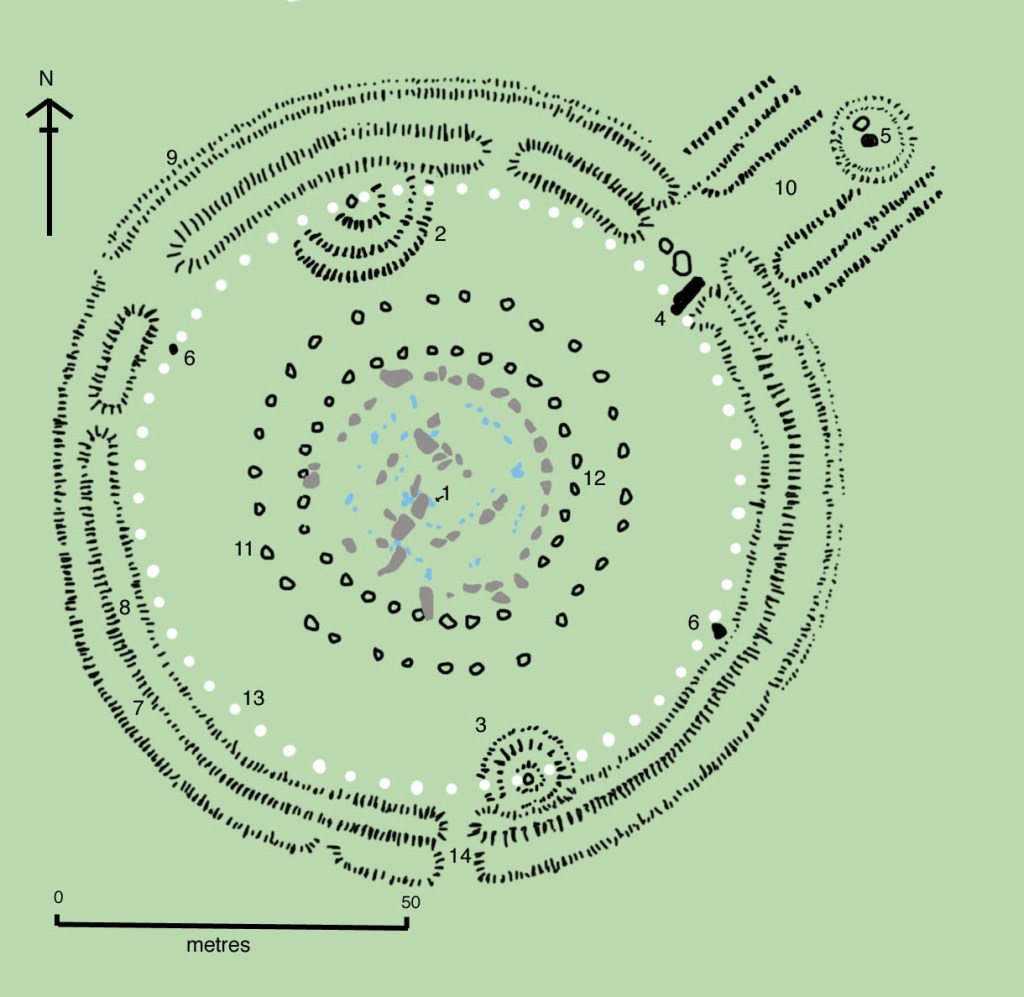

On the western side of Arran one finds the cosmically wonderful series of stone circles upon Machrie Moor. I visited the area the other day with my wee dog Daisy, who had escorted me to Arran with a load of stock for the Nine Bees. While she was cuddling up to the tourists I just sat awhile & ponder’d on the history of its ancient uses – long lost to us now; BUT, I believe I have made the first into exhuming the first bones of their religious rituals. The key is simple – understanding that a double circle of stones, such as those erected at Stonehenge & Machrie Moor (number 5), are astral mirrors of Saturn & its ring(s). This infers some kind of ancient worship of Saturn (Roman), or Cronos (Greek), of which there is definitive evidence, both epigraphical & archeological.

1: Epigraphical Evidence

In Plutarch’s moral essay ‘On the Face appearing in the Orb Of the Moon,’ the journeys of a certain ‘stranger, are narrated to him by Sylla the Carthagean, who had heard the tale himself from the servants of the temple of Cronus in Carthage, where the ‘stranger’ had recently visited. The key passage reads;

An isle Ogygian lies far out at sea,’ distant five days’ sail from Britain, going westwards, and three others equally distant from it, and from each other, are more opposite to the summer visits of the sun; in one of which the barbarians fable that Saturn is imprisoned by Jupiter, whilst his son lies by his side, as though keeping guard over those islands and the sea, which they call ‘the Sea of Cronos.’ The great continent by which the great sea is surrounded on all sides, they say, lies less distant from the others, but about five thousand stadia from Ogygia, for one sailing in a rowing-galley; for the sea is difficult of passage and muddy through the great number of currents, and these currents issue out of the great land, and shoals are formed by them, and the sea becomes clogged and full of earth, by which it has the appearance of being solid. That sea-coast of the mainland Greeks are settled on, around a bay not smaller than the Mæos, the entrance of which lies almost in a straight line opposite the entrance to the Caspian Sea. Those Greeks call and consider themselves continental people, but islanders all such as inhabit this land of ours, inasmuch as it is surrounded on all sides by the sea; and they believe that with the peoples of Cronos were united, later, those who wandered about with Hercules, and being left behind there, they rekindled into strength and numbers the Greek element, then on the point of extinction, and sinking into the barbarian language, manners, and laws; whence Hercules has the first honours there, and Cronos the second. When the star of Cronos, which we call the ‘Informer,’ but they ‘Nocturnal,’ comes into the sign of the Bull every thirty years, they having got ready a long while beforehand all things required for the sacrifice and the games … they send out people appointed by lot in the same number of ships, furnished with provisions and stores necessary for persons intending to cross so vast a sea by dint of rowing, as well as to live a long men in a foreign land. When they have put to sea, they meet, naturally, with different fates, but those who escape from the sea, first of all, touch at the foremost isles, which are inhabited by Greeks also, and see the sun seng for less than one hour for thirty days in succession; and this interval is night, ended with slight darkness, and a twilight glimmering out of the west.

A shorter version of all that would go something like this: Greek colonists settled North America – the great continent – sometime in the distant past. Every thirty years – when Saturn enters the sign of Taurus – some of them set off for a holy island, somewhere in the ocean beyond Britain, said to be where Cronos – ie the earthly deification Saturn – was imprisoned. Once on the island, the acolytes would remain an entire cycle of Saturn then move on, one of whom ended up in Carthage to tell the tale. Plutarch writes; ‘he had a strange desire and longing to observe the Great Island (forso, it seems, they call our part of the world), when the thirty years had elapsed, the relief-party having arrived from home, he saluted his friends and sailed away.’

2: Archeological Evidence

If we look at the plan of Stonehenge & the planet Saturn from above, the resemblances are stunning. The two sets of rings are there, as is the central sphere. Around the latter at Stonehenge are two circles of post-holes – the inner containing 29 holes & the outer 30. These numbers actually correspond to the moment when the long-term observation of Saturn corresponds with the long term observation of the sun. A synodic periods is the time required for a body of the solar system to return to the same position relative to the Sun as seen by an observer on the Earth, which in Saturn’s case is just over 378 days. After 29 of these periods, we reach the same number of days – more or less – as those ticked off by 30 solar years. Thus Plutarch is accurate when he describes Saturn worship on a 30 year solar cycle, & anyone who happen’d to be at Stonehenge, & the first circle by reading the post-holes calendar would have known when the new acolytes would have been setting off from ‘The Great Continent.’ In addition, there is also a ring of 56 chalk-filled holes, known as the Aubrey Holes, which could relate to 56 synodic periods of Saturn matching 717 lunar months, & the fact that one more synodic period equals 59 solar years – when the configurations of Saturn in the sky are repeated exactly two days later inthe solar year – perhaps to check the accuracy of the whole lunisolar calendar.

Ancient Observations of Saturn

The problem is – how did the ancients know about the rings of Saturn. We cannot see them with the naked eye, & apparently could not until the 17th century & Galileo’s invention of the telescope. HOWEVER, there are numerous & wondrous astronomical observations made by our ancients, among whom the ‘myth’ that Saturn was ringed, or held in chains, had spread far & wide. Perhaps the Greeks or some other people such as the Harrappan civilisation had possessed lenses adapted for the observation of celestial bodies, or were the rings around Saturn were visible to the naked eye at some time in the past? But however the ancients knew of the rings, they definitely knew.

In the Zend-Avesta it is said that the star Tistrya (Jupiter &, later, Venus) keeps Pairiko in twofold bonds, relating to Saturn’s girdle of two groups of rings. The text actually reads, “Tistrya, bright star, keeps Pairiko in twofold bonds, in threefold bonds.” A third ring around Saturn was observed in 1980!

The ‘Pairi’ phonetic of the Zend-Avesta is present in the New Zealand Maori name for Saturn, Parearau. The word pare denotes a fillet or headband; while arau means “entangled”—or perhaps “surrounded” in this case. IIn The Astronomical Knowledge of the Maori, Genuine and Empirical, published by Elsdon Best in Wellington, NZ in 1922, he writes;

Parearau, say the Tuhoe people, is a wahine tiweka (wayward female), hence she is often termed Hine-i-tiweka. One version makes her the wife of Kopu (Venus), who said to her, “Remain here until daylight; we will then depart.” But Parearau heeded not the word of her husband, and set forth in the evening. When midnight arrived she was clinging to another cheek, hence she was named Hine-i-tiweka. Parearau is often spoken of as a companion of Kopu. Of the origin of this name one says, “Her band quite surrounds her, hence she is called Parearau.”

An ancient engraved wooden panel from Mexico shows the family of the planets: one of them is Saturn, easily recognizable by its rings (see Kingsborough, Antiquities of Mexico (London, 1830), vol. IV)

The Egyptian apellative for Osiris was “the swathed” & in Egyptian legend Isis (Jupiter) swathes Osiris (Saturn).

The rings of Saturn are referred to by Aeschylus in his Eumenides: “He {Zeus} himself cast into bonds his aged father Cronus”

Mithraic representations of Kronos with his body encircled by a snake (see F. Cumont’s The Mysteries of Mithra [1903]) may attest to a memory of the rings of Saturn. Similarly, the Hindu Sani (the planet Saturn) shown in an ancient woodcut reproduced in F. Maurice, Indian Antiquities (London, 1800 – vol. VII), and described by the author as “encircled with a ring formed of serpents.”

The Babylonian Tammuz, who represents Saturn, was called “he who is bound.”

The statue of Saturn on the Roman capitol had bands around its feet.

An epigram of Martial reads, ‘these chains with their double fetter Zoilus dedicates to you, Saturnus. They were formerly his rings.”

In his Saturnalia, Macrobius writes, “Saturn, too, is represented with his feet bound together, and, although Verrius Flaccus says that he does not know the reason . . . Apollodorus says that throughout the year Saturn is bound with a bond of wool but is set free on the day of his festival.”

In the early second century AD, in his Fourteenth Discourse Dio Chrysostom writes, “And yet the King of the Gods, the first and eldest one, is in bonds, they say, if we are to believe Hesiod and Homer and the other wise men who tell this tale about Cronus.”

The shrines to Saturn in Roman Africa portrayed the god with his head surrounded “by a veil that falls on each of his shoulders,” in a way reminiscent of the planet’s rings. See J. Toutain, De Saturni Dei in Africa Romana Cultu (Paris, 1894)

… & so on. The fact that the ancients knew that Saturn was surrounded rings is beyond doubt, the only question is how they knew. Perhaps Saturn was closer to Earth in the past, or a telescopic eyeglass was invented by some long lost civilisation.

Cronos Worship off North-West Europa

Returning to Machrie Moor & its wonderful Saturnine first circle, one gets the feeling that this place especially of the Scottish stone circles is connected to Cronos worship. What else we know comes from Plutarch’s essay & some geographical speculations. A couple of weeks ago, while on Arran, I had a radio interview with the main Faroe Islands media company, who are thinking of putting a story of mine on their ‘Good Morning Faroe’ show. It basically goes that the prison island of Kronos was on the Faroe Islands themselves. My reasoning was that at the southern reaches of the islands – in Sudouroy, near the village of Lopra – stands a pyramidical peak – man made or natural – called Kirvi. Thename contains the initial phonetics of Kronos, & transchispers easily into the Akkadian (3rd-2nd millenium BC) version of Kronus – Kaiwan.

Kir-vi

Kai-wa-n

The fate of Cronus differs across texts, but with Orpheus he is incarcerated in the cave of Nyx, a cave of night or darkness, which perfectly reflects the extreme northerness of the Faroe Islands & their ‘eternal’ nights & days. In Plutarch’s moral essay, Obsolescence of Oracles (DeDefectu Oraculorum) one of the speakers is a certain Demetrius, who in an aside remarks upon the eternalimprisonment of Cronus. He relates that Cronus was confined in a cave on an island close to Britain, guarded as he slept by the ancient Briareüs and various other daimones (demi-gods). The Faroe Islands are indeed close to Britain, & even record a local folk lore about Holy Man inhabitaing Sudouroy long before the Norse arrived.

As for the prison island given in Plutarch’s ‘On the Face of the Moon,’ somewhere in the ‘Cronian Sea,’ for me it feels as if Ogygia is phantasy – there’s no island 5 days west of Britain – but the three islands referre’d too are Iceland & the two equidistant’ islands the Faroe archipelago,& Greenland. The latter island then fits well with it being 5000 stadia – about 600 miles, from the ‘Great Continent’ – North America.

The sea is difficult of passage and muddy through the great number of currents, and these currents issue out of the great land, and shoals are formed by them, and the sea becomes clogged and full of earth, by which it has the appearance of being solid. That sea-coast of the mainland Greeks are settled on, around a bay not smaller than the Mæos, the entrance of which lies almost in a straight line opposite the entrance to the Caspian Sea.

The Gulf of Maine is both on the same latitude as the Caspian Sea &about twice the size as the Sea of Azov, called ‘ Mæos’ in classical times. The Gulf of Maine is the best waterway that matches Plutarch’s ‘great number of currents, and these currents issue out of the great land.’ Under the surface, the elevated sea flooor of George’s Bank shapes the floow of currents and divides the Gulf of Maine from the Atlantic Ocean south of Cape Cod. Two major currents, the Labrador Current and Gulf Stream, meet just outside this boundary. Within the Gulf of Maine, the coastline alters the course of cold water owing into the Bay of Fundy, forming a gyre that deteects water southward. As ocean water moves throughout the gulf, it transports heat, sediment, nutrients, and a variety of small organisms unable to swim against the current known as plankton. Currents carry the building blocks of the ecosystem on which all other marine life depends. This of course matches Plutacrh’s ‘ shoals are formed by {the currents}, and the sea becomes clogged and full ofearth, by which it has the appearance of being solid.’

In the same area, the native American tribe known as the Iroquois seem related to the ancient Lycians of Anatolia, who were said to have originated in Crete when it was still polulated by pre-Greek ‘barbarians.’ Is it possible, then, that at the same time Crete sent out its ‘Greeks’ to Turkey, some also cross’d the Atlantic. The matriarchal gynococracy of the Iroquois certainly recalls the Lycians of Anatolia as described by Herodotus.

One custom {the Lycians} have which is peculiar to them, and in which they agree with no other people, that is they call themselves by their mothers and not by their father; and if one asks his neighbour who he is, he will state his parentage on the mother’s side and enumerate his mother’s female ascendants. If a woman who is a citizen marry a slave, the children are accounted to be of gentle birth; but if a man who is a citizen, though he were the first man among them, have a slave for wife or concubine, the children are without civil rights

Lafitau, an early 18th century missionary to the area, show that the name of the Thracian goddess Bendis was derived from the same root as the Iroquois endi or enni, which meant both the ‘day’ and the ‘sun’, the bringer of light. In addition, as each Iroquois village was divided into three ‘families’, of the Wolf, the Bear and the Turtle. So also were the Spartans divided into the three Dorian tribes, and archaic Rome had its Tities, Ramnes and Luceres, whose names are too ancient for us to understand. We also have the name ‘Iroquois’ itself, with its Basque roots (koa denotes where a person comes from) suggesting another link to ancient Eurasia.

Nevergreen

Brighton Fringe

28 th May – 27 th June, 2021

‘Nevergreen’ was a film created by a team of 10. Written by Gus Mitchell it was rehearsed, shot and edited during 2020 London lockdown. Freshly brought to this year’s Brighton fringe. Starring Katurah Morrish we were met with film footage of a living room that was minimal, though very stylish if dated. She took her time to introduce Rachel Carson who died at 56. Rachel was a writer, scientist, ecologist, and she in her time delved further than most into the world of nature and its assured

place in poetry.

Katurah’ energy as a huge fan of Rachel’s life and writings had her singing her praises in the indoor scenes of this movie/documentary/ theatrical event. We stepped with Katurah into a wood. It was a nice looking day, Rachel’s story was told intimately as we listened to her poetry that was so well constructed and sorted out.

She was alone outside in the wood and as time passed she told her emboldened thoughts “I grew up by the river.” Her illustrious poetry brought about such great happenings as she led her way in and out of existence using nature and imagination to make complete circles like the seasons passing.

The visual illustrations where all by the artist Ana Zoob, having movements of blues and greens and purples. The sound of bird song met with the sound of howling of wolves nearby. This contrasted with her narration of reading Rachel’s poetry that she spoke with long and big meaningful pronunciations.

Taking time to set the scenes she spoke with longing about the deep blue sea. She probed everything to find its essence, its journey, examining minutely with rhetorical resonations and revelations. Her questions were her greatest friend and she took on whatever journey she would find until the next journey.

The act of visiting the trees and rocks was shown as Katurah spoke in sincerity which was nice to be part of. It was told as if there and Katurah compelled us to listen with great focus on the things we were seeing in this journey into the beyond. Performed with a slight smile on her face, it began to speed up, as in a certain place a sense of urgency was introduced. All with wonderful visual art by Ana Zoob of souring and heartfelt illustrations of birds, insects who morphed in and out of life and served as a backdrop as the Direction of Eloise Poulton passed seamlessly.

But when she came to man she began to unravel. And with simple images of city skyline went into the destructive journey of man as they drag all else to the bottom in an inane and out of date striving for power. Rachel was saying that to be in nature is a far finer truth than it is to be separate or outside and without nature, logically suggesting that there is no place without nature, therefore we cannot be without it.

To strive into it, and think about it, and lie down in it and even gently touch a tree and rub leaves. And celebrate the poetry all around us and interwoven into all things. It had striking imagery and production and a very good case for the power of nature that is also in us, pleased and putting a slight smile on our face too. Making this point at the right time and certainly in the right place, But sharing it into an offering to the fringe of something so well written and finished.

Reviewer: Daniel Donnelly

Lord of Life

Brighton Fringe

28th May – 27th June, 2021

For our next act in the 2021 Brighton Fringe came the amazing ‘Lord of life’. The Rhino loomed like a hero in pen and ink illustrations of Sally Scott who could never have drawn like that without reverence and compassion for the magnificent animal. In gentle terms this piece of poetry was selected from Norman Morrissey’s book ‘For Rhino in a shrinking world’.

He wrote about an account he had with a Rhino who visited him in his tent when he was asleep one night. The smartly short piece delivered such an amazing an endearing comment upon these animals and the situation we are putting them in. How can we be harming these creatures who as Norman wrote and Harry Owen and Roddy Fox were to read we are torturing for ornament and so called medication.

With these feelings flying the words came with a soft and sweet flavour which confronted our idea of what these animals are; graceful teachers who ever so gently breathed upon him like a kind nurse to nurture him and to ease his day. He wrote that it was an old white rhino with such touching poetry as to bring joyful and gracious tears of love to our hearts, it was really that deep.

The book ‘ For Rhino in a shrinking world’ was written towards the end of Morrissey’s life, making it all the more poignant as we imagine his encounter to have been quite magical though obviously very real. It was a movie of illustrations put together by In Tandem (which is poetry put to imagery) from the spoken word recited by Owen and Fox.

A beautiful eulogy whose message came from the heart and broken heart of one who loved the animals. We were left at his side and were taken beside the rhino itself as it so compellingly lives and breathed among us. With the slightest of composure set the editing of the film as to marvel at. So simple, soft and real, and so true and right in this time.

Daniel Donnelly

On the Antiquities of Arran (1)

It has been almost seven years since my return to Burnley & my survey there into the Brunanburh battlefield. With every atom in my body almost completely regenerated, its time for another historical dig. This time its to the island of Arran, off the west coast of Scotland. For a domicile I have two areas, both at Corrie. The first is its splendid hotel where I will be making breakfasts in the morning, & the second is a derelict bunkhouse where I will be camping & cleaning up the mess for its aristocratic landlord in return for my staying there. Its not quite Howard Carter & Lord Canarvon at the Valley of the Kings, but it is a distinct version of such. The reason being is that on Kintyre there are connections to Mycyneae & 18th dynasty Egypt, while Arran is the name of a Bronze Age prince from what is called Caucasian Albania (modern day Georgia) – this region is where the Picts are supposed to come from originally, so there’s the starting point for my studies – there’s about 1000 new sites been uncovered on Arran by Historic Environment Scotland using LIDAR techniques (light detection & ranging), among which might be crucial clues which connect Arran to the Picts & places like Caucasian Albania – that’s my hunch.

Arran is a cosmic island – the Goat Fell area is stunning & towers over Corrie. The rest of the isalnd is also beautiful – there is a coastal road all the round & another which halves the island. On one side is the mainland & the other the fabulous finger stretch of Kintyre, giving the illusion of being at the heart of a gigantic lake – a dragons’ eye jewel set in a pearl of amber. There are enough hillforts & stone circles to get started on before I even attempt an investigation into the radarfound sites. There’s also plenty of philology to apply my chispological techniques onto, & , yes everything is sweet today having been given confirmation about my camping spot. I do have a little gout however, I;m on the verge of 45 & staying at a hotel isnt helping my alcohol-abstinence, but all is well really.

On Arrival On Arran

Remember the moment Arran came real

Sat on a stone by a sunbathing seal

Perch’d upon pyramid, sea splash & splish

& God has put a dog’s head on a fish

The eldest led like lions oer the bay

The youngest lifted heads & look’d my way

One shifted weight & slid into the sea

To settle on a shallow shelf near me

She knew I was a poet, I could tell,

Perhaps it was my solitary dell

Of silent thoughts, thro’ these I did commune

With nature’s ancyent, all-beauteous boon,

A sprig of scented poesy enters mind,

The future real, the past a dream behind.

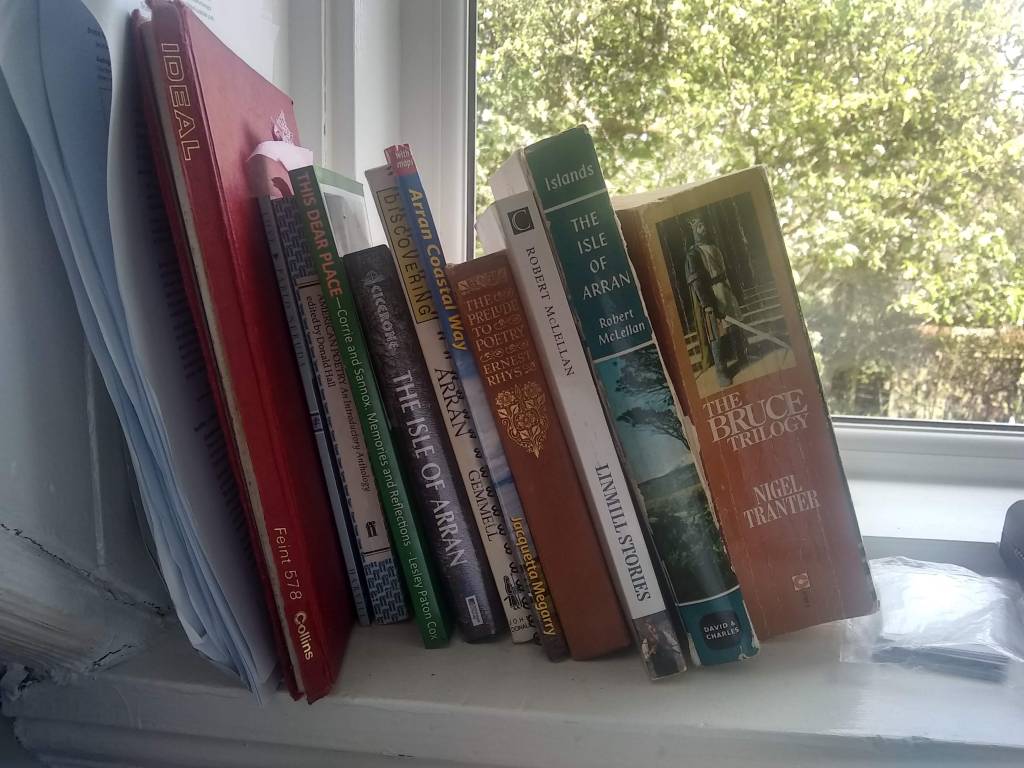

I shall be here now for several months. My library is already taking shape – the grandaughter of the famous Scottish playwright, Robert Mclellan, lives up at High Corrie in her grandfather’s cottage, & has already furnished me with some poetry – I shall be composing three conchordia while I am on the island. Also into the mix goes an almanc being created my my fellow breakfast chef/server, Tony, who is almost at the end of a three year composition of an incredibly comprehensive Arran almanac. He has leant me several books too – writing them down in a little notebook of his own so he’ll get them back. These include The Isle of Arran by the aforementioned Robert McLellan, & the Arran Coastal Way by Jacquetta Megarry.

Also in the library is Nigel Tranter’s ‘The Bruce Triology’ which I shall be raiding for one of my new conchordia – The King & the Spider – based on the early stages of the rise Robert The Bruce to the Scottish kingship. Another book is This Dear Place, written by a local lassie & ‘one of the Few’, Lesley Paton Cox, a labour of love which in her words, ‘wanted to speak about the people of our Corrie & Sannox past… to ensure that information about the folk of our two villages, their ancestors & their home here would be available for future generations.’ This book then planted a seed to create a conchord about the Highland Clearances. The other conchord will be MADCHESTER about the 89-90 halycon age of The Stone Roses & Happy Mondays.

So we’re off – the gardens of study & creativity has been planted & it is time to water them through the summer season…

Damian Beeson Bullen

Corrie

25/05/21

Lyra: Bristol Poetry Festival

Lyra: Lyra at Heart

Getting into this year’s two week online Bristol Poetry festival was a joy in itself, with another fine example of online organising. This time the team of Co-Directors and social programmers had something striking to say and the festival‘s aim and title of Festival Reconnection. To say that something was afoot would be a good reference as to the way that online poetry can hold the audience who are just out of being knocked by lockdown though it has now been lifted and hopefully businesses are coming back. So let’s come back from this 2021 Lyra’s protective theme of total and real Reconnecting.

It fell to Prof. Nick Groom to introduce us to and capture us by his expert story of a Bristol poet named Chatterton or Thomas Chatterton. Prof Groom who is a speaker, published with his themes of range and identity, his books include ‘The vampire, a new history’ which I haven’t read and know nothing about. In the fact that Groom’s experimentation in lecturing itself, would bring his world of writing set to explore Chatterton’s influence on Wordsworth’s writing and more.

—

Lyra: Prof. Groom: Chatterton’s books

He looked at Chatterton’s work and took the single lines from his poetry to examine how the premierist soon to be a gifted writer and how he early on went into creating through his stronghold phenominality we could have called him a phenominalist. Chatterton’s stories were very much influenced by his take on equality but his immortally kind and understanding stature only lasted until his suicide at the very tender age of 17. His tragedy was sealed. This tragedy shows him probably to be the youngest poet ever to write with such clarity in these manners, matters and more.

A Chatterton Quote would be, “Flowereth nodded on his head”, to me meaning something very gentle, to his, “…to hear his joyous song.” a line to speak for itself. Through most of his light and striving the dedicatory lecture compared Chatterton’s world to the world of today; finding reconnection in his remarkable relevance in the world of today and at the hand of humane starting to rebuild.

The Lyra festival was presented in association with the magnanimously rich in literature; Bristol Poetry Institute. Of whom a Bristol poet Caleb Parkin was in conversation with Madhu Krishnan. Their task was to hold a definitive discussion where the reconnection of our natures will and other natures to be taken in; to drink in the vast possibility’s in future by way of for everything. Going into a better and further look into the world of earth’s nature’s and the powerful nature of Poetry, which is why we’re all here.

A special thanks has to go to Danny Pandolfi a Co-Director of 2021 Lyra and Beth Calverley this years honoured festival poet, who does no end of positive work using poetry to help people to express themselves, she goes deep into this work but from what I saw always with a smile and amazing willingness.

Listening to her charm the place she read her poetry like it was from the sky above. And I would like to thank the other co-director Lucy English who is a spoken word educator and reader at Bath Spa University and is a Co-Director of ‘Liberated words’, so there was a coming together of big worlds in the poetry scene. And I would like to mention Josie Alford who was Marketing & Social media management and is said to have quite a stage presence.

—

—

Lyra: In the Event Of…

This event saw a great discussion and Q&A with Danny and Lucy in the launch of the theme of ‘Reconnection’, and all of its physical, natural and environmental implications. That led to poet Caleb Parkin whose pamphlet “wasted rainbow” was commented on by Nadu Chrisman to open up a discussion about the institutes and live world of spoken poetry. With our interests at hand the feedback opened to being interactive and somewhat centred around lockdown.

With the ecosystem and ecology of poets resulting in greatly helpful organisations whose textured aesthetics, novel form, narrative prose, seemed to surmount looking like (and helping us look into)) the life of the tree who are like their own point of origin and conclusion, seeking the elixir. Brought about loud and important ways to try and treat language specifically in a different way (a term of service that can disintegrate words, and lays out language).

Delving and enveloping the interesting tension in a poem of the individual feelings and focus for the reader and the listener. All of which proving a fascinated interest in dominance and seeing life on earth as a tilted experience. As a kind of “…perpetual loading icon.” That obviously never ends, or a “…pixelated fish”, perhaps indicating no resistance. The philosophy and reaches of the proposed ethics of poetry, within the festival frame plan took us from tip to toe. Offering completed poems and breaking down these poems to see fundamentals where questioning is really quite stylish and purposeful in the field of where to get ideas.

—

Lyra: Frogs and ‘Liberated Words’

Fiona Hamilton’s “Smell of fog”, reached in and plucked a frog from a naked patch of earth. Whose metaphor struck the almost dumbed senses of frogs that can’t self-isolate! The frogs as a species are a perfect depiction for fertility and interrelatedness. And in this offering was held the deeply fascinating work of eco poetry in action.

As a further introduction to ‘Liberated Words’,who from humble beginnings in the 2012 which was like a year at the Bath Spa University. Lucy directed Reconnections in her screening of poetry films that for Lyra were heritage, family heritage and connection. Sarah Tremlet produced books of poetry films commemorating her much loved film genre. She is a poetry film maker, theorist, and author of the ‘Poetics of Poetry’ film starting in 2005. In her meeting with Lucy English in 2010 they connected and decided to make poetry films about teenagers with autism, all in the name and deliberation of Liberated Words. ‘Liberated words’ and the ‘Arnolfini’ (the Bristol international Centre for Contemporary Art) have hung out many times over the years to the benefit of both.

—

All of this in the Reconnections: Poetry Film Screening

And in the subject of identity of things like minors, where there may be a duo of poetics of place with 5 examples of Lia Vile Madre who was a medieval gypsy whose heritage collections led to the object of the film ‘A bird on a tree’. So came: the ‘Bird’ Poem’ which was a commission from the Centre for Arts and Wellbeing, literally at the top of the tree. As the poetic wheels of motion rolled along the lines went from, “…feathers always fascinating us…” grouped with, “…love’s me to the winds.” And “each new bird roosts for me!” all hailing a triumphant noise to the sounds and senses of an earthly paradise. Leaving us with feelings of “…favourite colours, rainbows.”

The films scanned one after another in their very short form. Taking us through extraordinary stories of what they called “scattered feather dust.” And spoke of the “bloodlines” of poetry filmmaking with new departures from Ezabel Turner whose pamphlet ‘Wonder of the traveller’ put bones on the road in connection with rural communities. So the film ‘Blood lines’ was in colour and of a green forest at hand. With “…open bravado door”, something sensual and similar, coupled with “songs and seasons wave at you”. All of which completing her surmount of the old depth of reading and writing.

—

Lyra: Identity in the Mirror

In further film mode of poetry it was seen by Yvonne Redicks whose words became something confident! That creating this world of lyrical semblances in the green and purple lines of, “that night is steep.” With “…ring of his ashes…”, and in the “…line of figures…” completing the theme with a terrific comment on “…still born brother.”

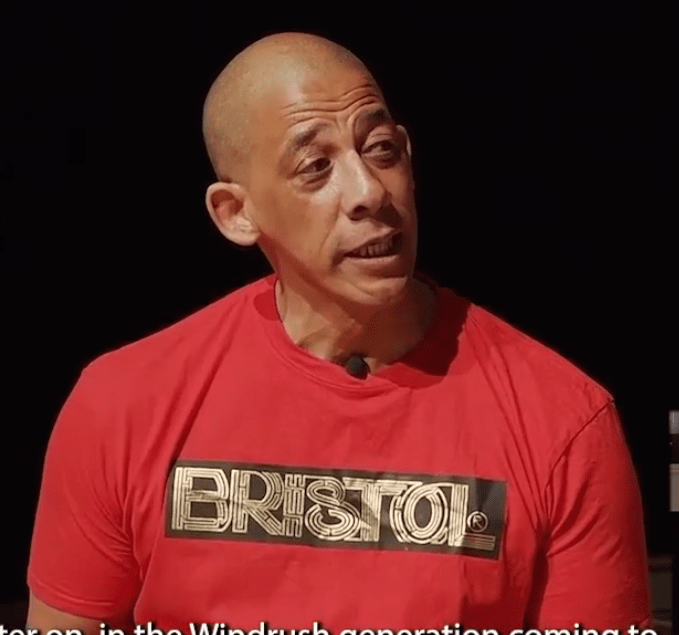

Moving away from film poetry we were invited right into a panel discussion that curtailed on programmes that were done and dusted, and showed us the many implications for thriving as a poet in the world of institutional and established themes whose opportunities being hopefully set to be fed and grow. Our discussion starred the inevitable voice of reason, Dr Edson Burton and with the voice of experience, Lawrence Hoo and facilitator (with some style), Ngaio Anyia.

The three of them were entrepreneurs at panel discussions, though there was a feeling of real relish from one being to another in this online way. Covering an abundance of tracks they talked about; Art & dissent: Bristol’s radical history. In this title the scope was placed for coverage to be their subjects and advertise them in the hope of bringing them to social matter.

About the plight of humanities African persuasion, communities build on being burnt to the ground classically, culturally and in the institutions. All of this has happened in what I can see as a sustained attempt to control these sections of the community’s across the world with a flag placed in Bristol at the Lyra. A jumping off point for Lyra was to heal the gaps of heinous injustices. I merely use this language because of how well the story was put together by the three even though only as a list of white crimes none of which were made with palatable events.

—

Lyra: Lawrence’s Analysis

Analysing Lawrence’s contributions against enslavement he looked at freedoms and civilisations, to build an unrelenting onset with his strength and willingness of experience. When talking with Dr Edson, the points were almost all reiterated. This was celebratory from the point of view of feeling free to speak out. The three did just that and asked us to do that too. There are so many things now going on in Britain, as to think something big may be happening, some kind of all-encompassing wave of truth brought about by writers and poets. But for the moment we will use the distinctive goings on in Bristol and in Lyra 2021.

Onto something inevitable in a made and unmade process. Keith Pipers words were eloquently articulate in a continuation of slave trade books, scenes and most importantly movements. And by now we were seeing familiar faces of the festival with for example Dr Edson talking about Pipers works and feelings. Also getting together with Meshin Decello and Vanessa Kisuule the animation films brought a presence that is unique to this type of art. Developing different voices and activism there was a direct energy alluding to a society that ignores poetry as it ignores people. But for that very reason the need is in offering a call of and for poets to be recognised.

In an examination of spoken word in the UK, seeing its history and significance, we welcomed Peter Bearder who further dissented the festivals accessibility. Looking at barriers he performed to the wider world with representative dealings and collaborations for presenting. Part of his creative, playful, physically competitive environment, and in the use of venues such as pubs and clubs. He showed us who could have the discipline for the performances and techniques. A surmounting elaboration of the modern music; dub, punk or hip hop. We could see the implications almost every time.

Though we frequently delved into the many themes of Reconnection the work was also brought into modern day focus. The focus that is needed to see our world as they expand in the relevance of the past or the past relevant to now as alluded to in Prof Groom’s sage like lecture in the events of Chatterton’s 100ds of years old legacy.

—

Lyra: Cutting Edge

Showing how surprising it is to see cutting edge life of many eras ago and in the time lines of seeing the future. Looking into the African situation of suffering can still be constructed by departmentalising it. Not the work or the poet but the theme. Pete used minority identities to compose and measure these abducted transferences. Cutting in with edgy progressiveness and offering a resistance against the all-powerful commercial marketing. Who if we look at it are also ran on a basis in slavery.

Using performance poetry to convey anything is always a striking phenomenon because of its nature, history and popularity. So for Langston Hughes it was a perfect opportunity to honestly talk about and discuss black America, and its history and its place in the world today. How do you cut through built up distrust? How do you even respond to terrible events? Again by breaking down of systems; for example exposure of Artists, or in the maturation of art form instead of the watered down work of the market.

—

—

Lyra: A Kick from Poetry Kitchen

In the aptly named Poetry Kitchen the in-depth knowledge took another turn at the deep end. Including and inviting us to the art of gathering scenes together by using criticism to provide a space for the hippest questions about the 20th Century. Spoken word phenomenon is as to what it is for having already been very impressed by it. It is a world where cherishing differences and critical language come together to agree on spoken word direction having already taken its place. Once again creating Reconnection’s and having a real love coming through bringing the delight of poetry into being; speak and ye shall hear. Lem Susey induced in us to a need for growing black poets becoming a very busy international hub to help create these things for communities and neighbours to share. It, as so much of Lyra festival is, grass root identity, to be striven for and used to debunk fresh acts of violence or the perpetration of…, to create a new culture with an open and tearful eye for the present as on the past.

—

Lyra: Reconnect

There was no end in this fortnight long online festival to the bountiful world of spoken or read or performed poetic‘s in stances and conundrums. All bound together and clasped together but all with poetic sincerity and connectivity in mind. Poetry of the world puts the highest thinking in place and watches with gentle turmoil as the acts of behaviour viewed across the globe. With this international conceptual thriving the reflections and commiserations shed light on the soul (or the planet) as a thing we know and will know for some time to come, even going back to the old religious celebrations. A healthy, natural absorption occurs; with the never ending qualities holding fun the day. Hence the festivals inclusivity of Lyra to talk loudly as with any other poetic organisations of today, in a world of bringing careful tenderness towards affliction’s of any kind.

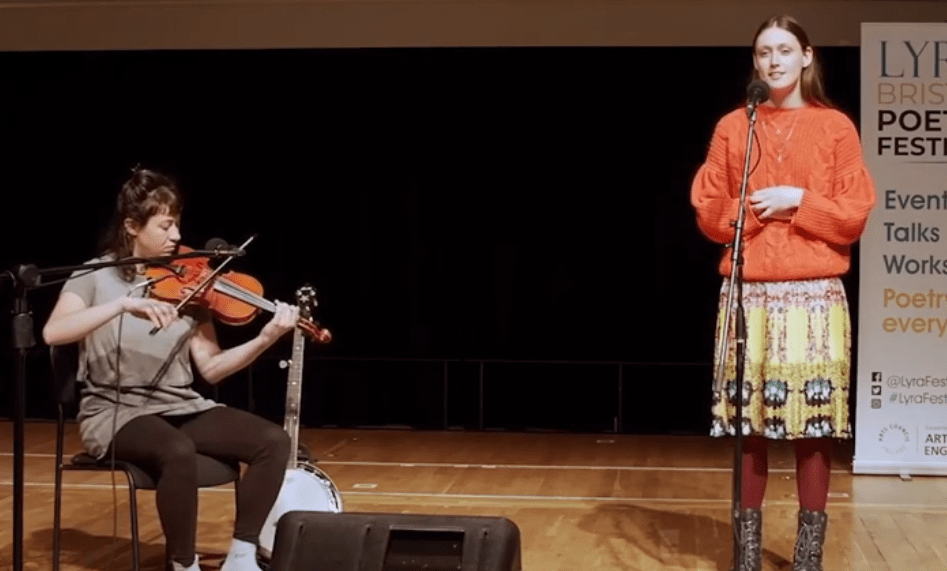

This is how good and well the distributing of poetry can get out and to as many populaces and cultures as is possible, enter Beth Calverley who was festival poet 2021. She is a 2020 British Life awards and Arts finalist with a collection of ‘Brave Faces & other smiles’ to accompany her verse and poetry press releases. She makes the endearing step towards mental wellbeing for all with her workshops and projects. She performed with her good friend Bethany Roberts whose songs and spoken word had them smiling in different ways.

—

Lyra: Make the Reconnections, Final Word

The aptly named “Spellbound” was a work of genius. It held the reflection of so many things that poured out of the violin, the music and the voice. We could easily see why Beth is flying and why she was named Festival Poet; imagine the lives she has personally touched. Then to the poems and poets; what this comes down to is written word of poetry. The listening to it, imagining it, understanding it and always making it your own! I’ll leave you with some quoted lines to sooth you but also to wake you up;

The wonderfully positive snippets of a place where; “…the weather was awful.” to the reasoning response “…comfort eyes.” And “…sense my voice friend…” to “…hold this yellow thread…” leaving us with “…sing myself undressed…”

To the bleak “…ghosts don’t bring wine…” looking for “…gold wrapping paper.” But within a “…clammy abyss…”

It was the protest styles that grabbed us with plentiful ideologies of how things play out and come to happen I leave you with the line; “Some poems force you to write them.”

———————————————————–

Reviewer: Daniel Donnelly

The Young Shakespeare (17): The Rival Poet

DECEMBER 1594

A Busy Christmas

By the Christmas of 1594, the 30 year old Shakespeare has fully evolv’d into a Theatre owner, company member and Playwright! On Mar 15th, 1595, there is a record of payment, via an entry in the accounts of the Treasurer of the Chamber to Chamberlain’s Men; for a December 27 or 28 performance.

To William Kempe, William Shakespeare & Richard Burbage, servaunts to the Lord Chamberleyne, upon the Councelle’s warrant dated at Whitehall xv. to Marcij… for twoe severall comedies or enterludes shewed by them before her majestie in Christmas tyme laste part viz St. Stephens daye and Innocents daye xiijli vjss vijd, and by way of her majesties Reward vjli iiijd, in all xxli.

By March 15, 1595, and inferentially by Christmas 1594, William Shakespeare had become a leading member of his company, the Lord Chamberlain’s players, sufficiently senior to serve with William Kempe and Richard Burbage as a financial trustee, receiving two £10 payments “for twoe seuerall Comedies or Enterludes shewed by them before her maiestie in Christmas tyme laste paste viz vpon St Stephens daye & Innocents daye.”

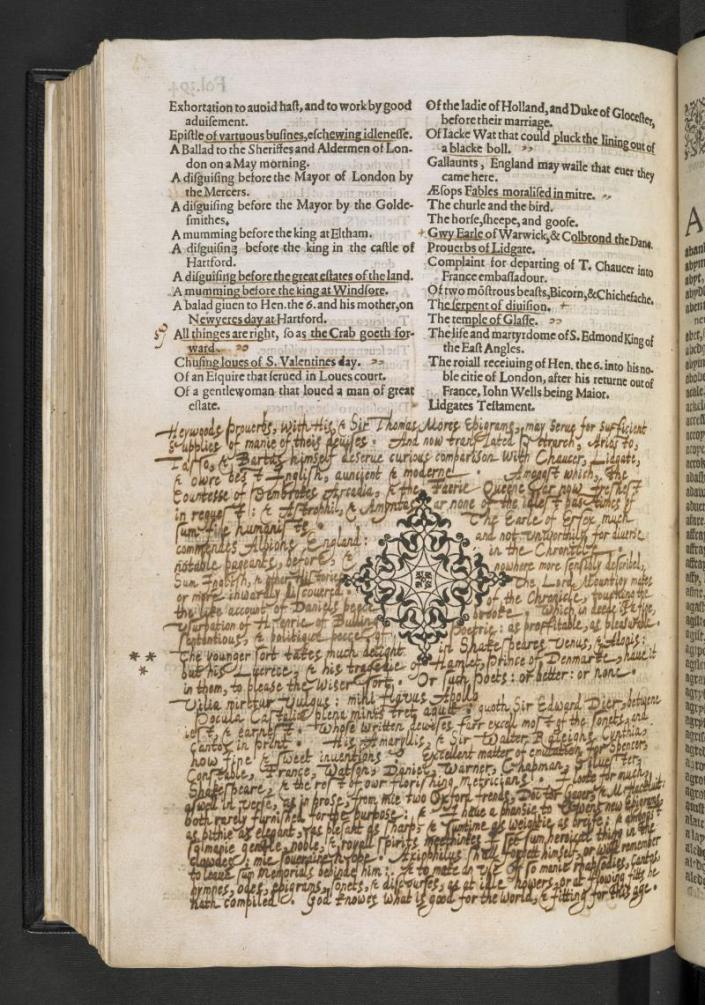

In 28 December 1594 the first known performance of Shakespeare’s “The Comedy of Errors” took place in Gray’s Inn Hall, as part of the Inn’s Christmas festivities. These were recorded in detail in the “Gesta Grayorum”, a contemporary account of the performance, but not published until 1688. It tells us that “A Comedy of Errors (like to Plautus his Menechmus) was played by the Players” in Gray’s Inn Hall on December 28, 1594, amid an evening of general confusion that led to the occasion being called the “Night of Errors.”

The Gesta Grayorum, printed in 1688 from a manuscript apparently passed down from the 1590s is an account of the Christmas revels by the law students at Gray’s Inn in 1594. In the text reproduced below the references to the High and Mighty Prince, Henry Prince of Purpoole, our Prince of State, are to the mock prince crowned for the occasion from among the students, a sort of prince of misrule. The document is important for its clear reference to Shakespeare’s company–the players–and unmistakable references to Shakespeare’s The Comedy of Errors, performed on this night of December 28, 1594 (“Innocents-Day”). It also contains an enigmatic references to (perhaps) certain elements in Love’s Labour’s Lost which are also reproduced below.

The next grand Night was intended to be upon Innocents-Day at Night ; at which time there was a great Prefence of Lords, Ladies, and worfhipful Perfonages, that did expect fome notable Performance at that time ; which, indeed, had been effected, if the multitude of Beholders had not been fo exceeding great, that thereby there was no convenient room for thofe that were Actors ; by reafon whereof, very good Inventions and Conceipts could not have opportunity to be applauded, which otherwife would have been great Contentation to the Beholders. Againft which time, our Friend, the Inner Temple, determined to fend their Ambaffador to our Prince of State, as fent from Frederick Templarius, their Emperor, who was then bufied in his Wars againft the Turk. The Ambaffador came very gallantly appointed, and attended by a great number of brave Gentlemen, which arrived at our Court about Nine of the Clock at Night. Upon their coming thither, the King at Arms gave notice to the Prince, then fitting in his Chair of State in the Hall, that there was come to his Court an Ambaffador from his ancient Friend the State of Templaria which defired to have prefent Accefs unto His Highnefs ; and fliewed his Honour further, that he feemed to be of very good fort, becaufe he was fo well attended ; and therefore defired that it would pleafe His Honour that fome of his Nobles and Lords might conduct him to His Highnefs’s Prefence ; which was done. So he was brought in very folemnly, with Sound of Trumpets, the King at Arms and Lords of Purpoole making to his Company, which marched before him in order. He was received very kindly of the Prince, and placed in a Chair befides His Highnefs, to the end that he might be Partaker of the Sports intended. But firft, he made a Speech to the Prince, wherein he declared how his excellent Renown and Fame was known throughout all the whole World ; and that the Report of his Greatnefs was not contained within the Bounds of the Ocean, but had come to the Ears of his noble Sovereign, Frederick Templarius where he is now warring againfl the Turks, the known Enemies to all Christendom; who having heard that His Excellency kept his Court at Graya, this Chriftmas, thought it to ftand with his ancient League of Amity and near Kindnefs, that fo long hath been continued and increafed by their noble Anceftors of famous Memory and Defert, to gratulate his Happinefs, and flourifhing Eftate ; and in that regard, had fent him his Ambaffador, to be refiding at His Excellency’s Court, in honour of his Greatnefs, and token of his tender Love and Good Will he beareth to His Highnefs; the Confirmation whereof he efpecially required, and by all means poffible, would ftudy to increafe and eternize: Which Function he was the more willing to accomplish, becaufe our State of Graya did grace Templaria with the Prefence of an Ambaffador about thirty Years fince, upon like occafion. Our Prince made him this Anfwer, That he did acknowledge that the great Kindnefs of his Lord, whereby he doth invite to further degrees in firm and Loyal Friendfhip, did deferve all honourable Commendations, and effectual Accomplifhment, that by any means might be devifed ; and that he accounted himfelf happy, by having the fincere and ftedfaft Love of fo gracious and renowned a Prince, as his Lord and Mafter deferved to be efteemed ; and that nothing in the World fhould hinder the due Obfervation of fo inviolable a Band as he efteemed his Favour and Good Will. Withal, he entred into Commendations of his noble and courageous Enterprizes, in that he chufeth out an Adverfary fit for his Greatnefs to encounter with, his Honour to be illuftrated by, and fuch an Enemy to all Christiendom as that the Glory of his Actions tend to the Safety and Liberty of all Civility and Humanity ; yet, notwithstanding that he was thus employed, in this Action or honouring us, he mewed both his honourable Mindfulnefs of our Love and Friendfhip, and alfo his own Puiffance, that can afford fo great a number of brave Gentlemen, and fo gallantly furnifhed and accomplimed : And fo concluded, with a Welcome both to the Ambaffador himfelf, and his Favourites, for their Lord and Mailer’s fake, and fo for their own good Deferts and Condition.

When the Ambaflador was placed, as aforefaid, and that there was fomething to be performed for the Delight of the Beholders, there arofe fuch a difordered Tumult and Crowd upon the Stage, that there was no Opportunity to effect that which was intended : There came fo great a number of worshipful Perfonages upon the Stage, that might not be difplaced ; and Gentlewomen, whofe Sex did privilege them from Violence, that when the Prince and his Officers had in vain, a good while, expected and endeavoured a Reformation, at length there was no hope of Redrefs for that prefent. The Lord Ambaffador and his Train thought that they were not fo kindly entertained, as was before expected, and thereupon would not ftay any longer at that time, but, in a fort, difcontented and difpleafed. After their Departure the Throngs and Tumults did fomewhat ceafe, although fo much of them continued, as was able to diforder and confound any good Inventions whatfoever. In regard whereof, as alfo for that the Sports intended were efpecially for the gracing of the Templarians it was thought good not to offer any thing of Account, faving Dancing and Revelling with Gentlewomen; and after fuch Sports, a Comedy of Errors (like to Plautus his Menechmus) was played by the Players. So that Night was begun, and continued to the end, in nothing but Confufion and Errors; whereupon, it was ever afterwards called, The Night of Errors.

This mifchanceful Accident forting fo ill, to the great prejudice of the reft of our Proceedings, was a great Difcouragement and Difparagement to our whole State ; yet it gave occafion to the Lawyers of the Prince’s Council, the next Night, after Revels, to read a Commiffion of Oyer and Terminer, directed to certain Noblemen and Lords of His Highnefs’s Council, and others, that they would enquire, or caufe Enquiry to be made of fome great Diforders and Abufes lately done and committed within His Highnefs’s Dominions of Purpoole, efpecially by Sorceries and Inchantments ; and namely, of a great Witchcraft ufed the Night before, whereby there were great Diforders and Mifdemeanours, by Hurly-burlies, Crowds, Errors, Confufions, vain Reprefentations and Shews, to the utter Difcredit of our State and Policy.

The next Night upon this Occafion, we preferred Judgments thick and threefold, which were read publickly by the Clerk of the Crown, being all againft a Sorcerer or Conjurer that was fuppofed to be the Caufe of that confufed Inconvenience. Therein was contained, How he had caufed the Stage to be built, and Scaffolds to be reared to the top of the Houfe, to increafe Expectation. Alfo how he had caufed divers Ladies and Gentlewomen, and others of good Condition, to be invited to our Sports; alfo our deareft Friend, the State of Templaria, to be difgraced, and difappointed of their kind Entertainment, deferved and intended. Alfo that he caufed Throngs and Tumults, Crowds and Outrages, to difturb our whole Proceedings. And Laftly, that he had foifted a Company of bafe and common Fellows, to make up our Diforders with a Play of Errors and Confufions ; and that that Night had gained to us Difcredit, and itfelf a Nickname of Errors. All which were againft the Crown and Dignity of our Sovereign Lord, the Prince of Purpoole.

Under Colour of thefe Proceedings, were laid open to the View, all the Caufes of note that were committed by our chiefefl Statesmen in the Government of our Principality ; and every Officer in any great Place, that had not performed his Duty in that Service, was taxed hereby, from the higheft to the loweft, not fparing the Guard and Porters, that fuffered fo many difordered Perfons to enter in at the Court-Gates : Upon whofe aforefaid Indictments, the Prifoner was arraigned at the Bar, being brought thither by the Lieutenant of the Tower (for at that time the Stocks were graced with that Name;) and the Sheriff impannelled a Jury of Twenty four Gentlemen, that were to give their Verdict upon the Evidence given.

Shortly after this Shew, there came Letters to our State from Frederick Templarius ; wherein he defired, that his Ambaffador might be difpatched with Anfwer to thofe Things which he came to treat of So he was very honourably difmiffed, and accompanied homeward with the Nobles of Purpoole : Which Departure was before the next grand Day. The next grand Night was upon Twelfthday at Night; at which time the wonted honourable and worfhipful Company of Lords, Ladies and Knights were, as at other times, affembled ; and every one of them placed conveniently, according to their Condition. And when the Prince was afcended his Chair of State, and the Trumpets founded, there was prefently a Shew which concerned His Highnefs’s State and Government : The Invention was taken out of the Prince’s Arms, as they are blazon’d in the beginning of his Reign, by the King at Arms. Firft, There came fix Knights of the Helmet, with three that they led as Prifoners, and were attired like Monfters and Mifcreants. The Knights gae the Prince to underftand, that as they were returning from their Adventures out of Ruffia, wherein they aided the Emperor Ruffia, againft the Tartars t they furprized thefe three Perfbns, which were confpiring againfl His Highnefs and Dignity: and that being apprehended by them, they could not urge them to difclofe what they were : By which they refting very doubtful, there entred in the two Goddeffes, Arety and Amity; and they faid, that they would difclofe to the Prince who thefe fufpected Perfons were; and thereupon shewed, that they were Envy Malecontent and Folly : Which three had much mifliked His Highnefs’s Proceedings, and had attempted many things againft his State; and but for them two, Fertile and United Friendfhip, all their Inventions had been difappointed. Then willed they the Knights to depart, and to carry away the Offenders ; and that they themfelves fhould come in more pleafing fort, and better befitting the prefent. So the Knights departed, and Fertile and Amity promifed, that they two would fupport His Excellency againft all his Foes whatfoever, and then departed with moft pleafant Mufick. After their Departure, entred the fix Knights in a very ftately Mask, and danced a new devifed Meafure ; and after that, they took to them Ladies and Gentlewomen, and danced with them their Galliards, and fo departed with Mufick. Which being done, the Trumpets were commanded to found, and then the King at Arms came in before the Prince, and told His Honour, that there was arrived an Ambaffador from the mighty Emperor of Ruffia and Mofcovy, that had fome Matters of Weight to make known to His Highnefs. So the Prince willed that he fhould be admitted into his Prefence ; who came in Attire of Russia, accompanied with two of his own Country, in like Habit.

The confusion has been well explained by Alan H. Nelson;

While different theatre historians offer different explanations of the conflicting evidence, it is at least within the realm of possibility that the Lord Chamberlain’s players, Shakespeare among them, had contracted to present a play at Gray’s Inn on the evening of December 28th 1594. For some unknown reason the company was ordered to perform at court on the same evening, perhaps by last-minute royal command. Having discharged their responsibilities at Greenwich, the company returned by boat to London, appearing at Gray’s Inn near midnight among scenes of utter chaos.

1594-95

RICHARD BARNFIELD, THE RIVAL POET

If music and sweet poetry agree,

As they must needs, the sister and the brother,

Then must the love be great ’twixt thee and me,

Because thou lov’st the one and I the other.

Dowland to thee is dear, whose heavenly touch

Upon the lute doth ravish human sense;

Spenser to me, whose deep conceit is such,

As passing all conceit, needs no defence.

Thou lov’st to hear the sweet melodious sound

That Phœbus’ lute, the queen of music, makes;

And I in deep delight am chiefly drowned

Whenas himself to singing he betakes:

One god is god of both, as poets feign,

One knight loves both, and both in thee remain.

The above sonnet was sometimes attributed to Shakespeare as it appeared anonymously in the Shakespeare-heavy ‘The Passionate Pilgrim’ of 1599. However, it has also appeared in Richard Barnfield’s ‘Poems in Divers Humors,’ the year before. What this does show is that Barnfield & Shakespeare were cut from the same cloth. Earlier in our essay on the Young Shakespeare we look’d at Leo Dougherty’s research into the Richard Barnfield, Shakespeare & Stanley sonneteering triangle, out of which body of work we were able to identify the time & place of the Dark Lady sonnets. We also came to understand how the homoerotic Richard Barnfield was the ‘Rival Poet’ of the sonnets, with Dougherty adding; ‘my inference… if they are about the same man, then the carryings on of Shakespeare, his ‘fair man’, & his dark lady took place before Shakespeare’s period of poetic rivalry.’ Here is one of the classic ‘rival poet’ sonnets from Shakesepaeare’s pen.

Was it the proud full saile of his great verse,

Bound for the prize of (all to precious) you,

That did my ripe thoughts in my braine inhearce,

Making their tombe the wombe wherein they grew?

Was it his spirit, by spirits taught to write,

Aboue a mortall pitch, that struck me dead?

No, neither he, nor his compiers by night

Giuing him ayde, my verse astonished.

He nor that affable familiar ghost

Which nightly gulls him with intelligence,

As victors of my silence cannot boast,

I was not sick of any feare from thence,

But when your countinance fild vp his line,

Then lackt I matter, that infeebled mine

Having arrived ourselves at the year of 1595, it is time to look at their relationship in more detail, beginning with Leo Daugherty.

A few years down the road, & increasingly mindful of Haines’ caution to Buck Milligan that Shakespeare’s sonnets are, ‘the happy hunting ground of all minds that have lost their balance,’ I nonetheless came to conclude from the evidence I accumulated that not only was Barnfield’s Ganymede the sixth Earl of Derby, William Stanley, but also that Barnfield published poems from 1594 (including over twenty homoerotic love sonnets) were in dialogue with some of Shakespeare’s own homoerotic sonnets to his Fair Youth… we hardly have reason to be very surprised if, after all, Shakespeare’s beloved & revered male addressee might turn out to be William Stanley.’

Daugherty bases his reasoning on a ‘sonnetteering conversation’ played out between Shakespeare & a younger poet, Richard Barnfield, who officialy dedicated his series of homoerotic sonnets to Stanley. Barnfield published his sonnets in 1593, dedicating them to Stanley in the most florid style; ‘To the Right Honorable, and most noble-minded Lorde, William Stanley, Earle of Darby, &c. Right Honorable, the dutiful affection I beare to your manie vertues, is cause, that to manifest my loue to your Lordship, I am constrained to shew my simplenes to the world. Many are they that admire your worth, of the which number, I (though the meanest in abilitie, yet with the formost in affection) am one that most desire to serue, and onely to serue your Honour. Small is the gift, but great is my good- will ; the which, by how much the lesse I am able to expresse it, by so much the more it is infinite.’ Barnfield continues on like this for quite a bit, & it really does feels like he is among the inspirations for Shakespeare’s moaning about a ‘rival poet’ in his sonnets;

O! how I faint when I of you do write,

Knowing a better spirit doth use your name,

And in the praise thereof spends all his might,

To make me tongue-tied speaking of your fame.

So, in the years following 1593, we seem to be witnessing Shakespeare continuing his sonnet dialogue with Stanley, this time rather miff’d there’s a johnny-cum-lately in the mix. There are many comparisons between the two poets’ work, from poetical conceits to phraseology

Come thou hither, my friend so pretty, all riding on a hobby horse; Either make thyself more witty or again renew thy force (Barnfield)

Sweet love, renew thy force; be it not said

Thy edge should blunter be than appetite,

Which but to-day by feeding is allayed,

To-morrow sharpened in his former might:

So, love, be thou, although to-day thou fill

Thy hungry eyes, even till they wink with fulness,

To-morrow see again, and do not kill

The spirit of love, with a perpetual dulness.

Let this sad interim like the ocean be

Which parts the shore, where two contracted new

Come daily to the banks, that when they see

Return of love, more blest may be the view;

As call it winter, which being full of care,

Makes summer’s welcome, thrice more wished, more rare. (Shakespeare)

The two extracts above are solidly connected by the phrase ‘renew thy force.‘ In the next sonnet – with Shakespeare again sounding miff’d off at other poets writing for Stanley – a key phrase is ‘amend thy style,’ which turns up in Barnfields ‘Greene’s Funerals’ of 1594.

So oft have I invoked thee for my Muse,

And found such fair assistance in my verse

As every alien pen hath got my use

And under thee their poesy disperse.

Thine eyes, that taught the dumb on high to sing

And heavy ignorance aloft to fly,

Have added feathers to the learned’s wing

And given grace a double majesty.

Yet be most proud of that which I compile,

Whose influence is thine, and born of thee:

In others’ works thou dost but mend the style,

And arts with thy sweet graces graced be;

But thou art all my art, and dost advance

As high as learning, my rude ignorance. (Shakespeare)

Amend thy style? who can? who can amend thy style

For sweet conceit?

Alas the while

That any such as thou shouldst die

By fortunes guile (Richard Barnfield)

This poetic rivalry was short, brief, & bristling with excellent writing – however, their competition would soon be trump’d by the arrival of a new rival to Stanley’s affections – his future wife.

JANUARY 1595

William Stanley Marries

On January 26th, 1595, at Greenwich Palace, William Stanley married Elizabeth de Vere, daughter of the 17th Earl of Oxford and granddaughter of Lord Burghley. The royal venue was probably a gift from the Queen herself, for de Vere was her maid of honour. Robert Cecil in a letter says at least one play had been prepared to entertain the many guests, with a dance to close the night. That four days after the wedding there was ceremony in Lord Burghley’s House connects with a line in Midsummer Night’s Dream. The 30th of January 1595 was a New Moon, which leads us to the first lines of the play

Now, fair Hippolyta, our nuptial hour

Draws on apace. Four happy days bring in

Another moon. But, oh, methinks how slow

This old moon wanes. She lingers my desires,

Like to a stepdame or a dowager

Long withering out a young man’s revenue.

One of MND’s characters is Titania, the Queen of the Fairies, whose presence could well have entertain’d the onwatching Elizabeth I herself.

With the main storyline of MND being the wedding of Theseus and Hippolyta, MND is Shakespeare’s definitive paean to marriage, a bridal masque of sorts, & so much so that even the play within a play – Pyramus and Thisbe – is also about a {forbidden} marriage.

MND was enter’d into the Stationer’s Register on 8th October, 1600, & printed later that year; the title-page claims that the play “hath been sundry times publickely acted” by the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, with Francis Meres mentioning it among Shakespeare’s plays in 1598. A 1594 date for its composition is suggested by an allusion to Edmund Spenser’s Epithalamion, an ode written to his own bride, Elizabeth Boyle, on their wedding day in 1594. In addition, by the bulk of contemporary testimony, the play’s cold, wet summer, followed by a poor harvest, also points to 1594. There is also the mechanicals’ discussion (3.1. 27–42), concerning the advisability of bringing a lion on stage for fear of frightening the ladies. This passage seems based on an incident which occurred at the feast for the baptism of Prince Henry of Scotland on 30 August 1594. As King James dined, a chariot was drawn in by a blackamoor; he was a substitute for the real lion which had been intended, “because [the lion’s] presence might have brought some feare to the nearest”. (For more details, see – A True reportarie of the most triumphant, and royal accomplishment of the baptisme of the most excellent, right high, and mightie prince, Frederik Henry; by the grace of God, Prince of Scotland Solemnized the 30. day of August. 1594).

The marriage of William Stanley & his becoming the Earl of Derby seems a perfect time to end this Young Shakespeare series. It had been a decade since the two Williams had adventured across Europa, at the end of which Shakespeare was well on his way to becoming a superstar for all ages. The private & youthful lust & love that they had shared on the road had dissipated onto the stage of time & its cast of thousands, tho’ of course many remembrances of their tourings were still to find an eternity through Shakespeare’s pen.

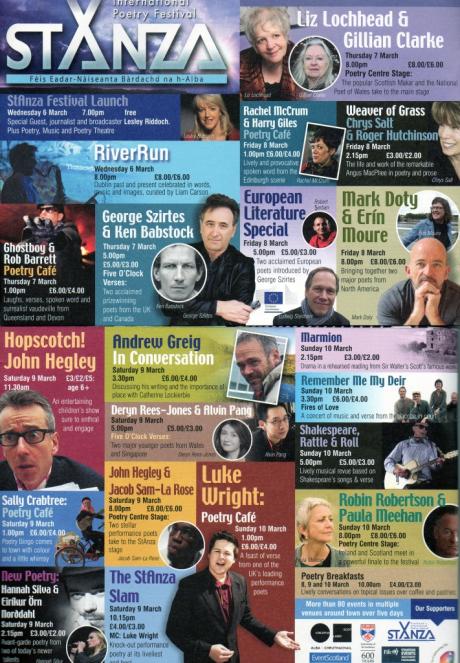

StAnza Poetry Festival 2021

St Andrews

March 6th – 14th

The Stanza International Poetry Festival took place online from 6th to 14th March. Stanza was born in 1997, the brainchild of three poets deeply qualified in the field, Brian Johnstone, Anne Crowe and Gavin Bowd. Over the decades it has built up a standing as a leading place at the head of world poetry. Brian Johnstone, the poet and writer, is part of Edinburgh Shore Poets, with a particular interest in live poetry. Brian served as Festival Director from 2000-2010. Anne Crowe has many publications and prizes, and has translated into Castilian, Catalan, German and more, and Gavin Bowd teaches in St Andrews University. The first Stanza Festival launched on National Poetry Day in 1998, only a year after its conception.

This year, there wasn’t a single poet who did not strive and succeed in the field wither older or younger. having many honorary or volunteered for positions in the festival life itself. But the top seats had to go to the amazing Eleanor Livingstone who took us around as the Festival Director, Louise Robertson, on Press & Media and Annie Rutherford, Programme Co-ordinator.

The pre-festival 5th March Panel discussion I found extremely interesting. I was captured by all the great styles of the written word. Taking off, with an expert discussion about the current goings on in the ‘European regions progress in literary culture’: an assessment of the progress culturally in considering brand new approaches. With an emphasis on understanding of the said European literary culture and regions, whether or not the writing is concerned enough with winning a battle of creating real roots outside the English dominant language. With the good news of their beginning to be or not of new infrastructures that are coming through with fresh lenses.

The Event ‘Trafica’, a radio initiative/European project talked very specifically about its identity and the giant world of creating serious funding that is met a little in the creating of inroads into how to qualify for funding. With Dostoevsky mentioned; the getting out of politics in poetry or at least in the intake of greater cultures, was dreamed of with the belief that poetry is of the Alchemy of the spirit and a gorgeous wish to move far away from being anything narrow minded. All coming with the initial supra courageous step of leaving your home country, finding its way to Stanza.

Concrete Poetry & Insta Poetry

My introduction to this came in a ‘Meet the artist’ event concerning the concept of concrete poetry and Insta poetry; The Insta was explored in Chris McCabe’s ‘For every day’ a poetry book with two poets in what is called a poem atlas, an idea of high mountains and frequent views both bad and good (to put it in simple terms). Bringing with it uncomfortableness and an openness which through the poetry went into the performances and readings.

Insta poetry is helping herald the quiet yet substantial revolution of poetry to the new and younger audiences. With its new forms of poetry, such as photo poetry. All made around the two fresh prospects of Concrete and Insta poetry. Giving the poets a chance to convey personal interests in the nature of concrete poetry measuring its effect upon itself with the natural components of words.

Political poetry then would have helped in the creating of a platform for forming options for the artist to reach their own outreaching platforms. They talked about the marvel that is online eventing calling it a dynamic in the world of Instagram critique. Astra Papachristodoulon asking us to travel beyond the book. Thinking instead about using her own brought objects to the table, a very wavy broadband of a subject. She also gave the example of using sculpture to make sense of her feelings, in particularly mixing sculpture with poetry. So, the highest abstracts were made possible in her very own art form.