Vint Bridge At Shiskine

One

It is said on Arran the wind has a soul, & that this soul has a voice, & that sometimes it sings. A seasonal soul, that is, for thro’ the darker months of the year the wind certainly found something to sing about. Wagnerian, some Arranites would fondly recall when visiting some sultrier clime.

The empty spaces of an Arran winter are a complete antithesis to its tourist-teeming summer acres, for during the shorter days only 5000 happy residents compete for over two hundred square miles. The island of Malta, by contrast, despite being the same physical size as Arran, is home to half a million. Lots of fun to be had at the ‘navel of the world,’ whatever time of year. “But one must keep oneself occupied,” mused Beatrice, or Betty MacKinley, to herself, at the other European extreme, one January evening which offer’d nothing but extreme boredom. Exactly one week later she had formally enroll’d in the Arran Bridge Club.

By the following winter she was playing vint three times a week – on Tuesdays, Thursdays, & Saturdays. Sunday was of course the most suitable day for cardplay, but had to be set aside for island duties, such as family visits, church services & other religious misdemeanours. They were playing vint, a kind of auction bridge, because the Arran Bridge Club had voted against allowing such an exotic variant into their dusty old cloisters, & thus a schisming splinter-group had form’d in the Shiskine valley.

They play’d as follows; the corpulent & hot-temper’d Robert, or Bobby Mentieth play’d with Archibald, or Archie Alexander; while Betty partner’d her brother, the morose John, or Jock, as this forename rolls throughout the Scots. The reason Betty gave was that, to play against her brother gave her no sort of interest, for if one lost, the other won, & although the stakes were insignificant, the money would still be going to the family. She never could understand the use of playing a game for playing’s sake.

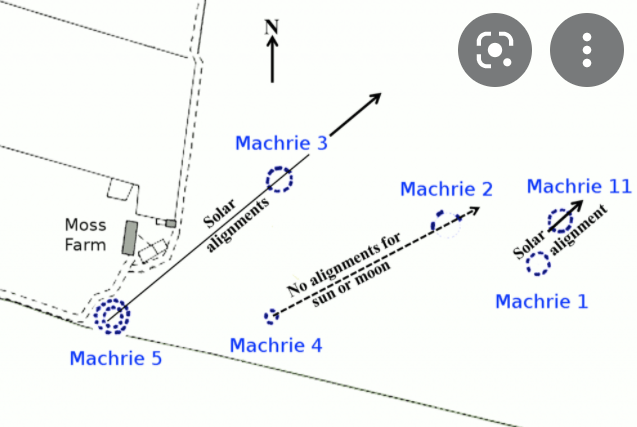

The players always assembl’d in Jock’s house – he had a lovely conservatory overlooking Machrie Moor, the sea & the ever-changing Atlantic weather systems. He lived alone, so there was perfect silence for the games, except for an occasional piece of classical music on Saturdays, which sometimes revolv’d under the soft spike of a gramophone needle. Jock was a widower; he lost his wife in the second year of their marriage, & for almost six months lay sick in an Edinburgh hospital for mental afflictions. His sister was five years younger, & the veritable baby of the party, at a not so tender forty-three years of age. She was also unmarried, but like her brother she had been wedded once, with the divorce being catalyzed like so. ‘Tata,’ a Russian prima donna who was living & working in Glasgow at the same time as Betty & her husband, had call’d upon the marital home quite spontaneously. Her husband was a painter of scenery at the city opera house, while Tata was supposed to be a soprano, but whose pitch wilted into mezzo from time to time. Nobody ever dared mention it, however, else incur the wrath of a corner’d, glorious Muscovite.

Betty had been washing vegetables in anticipation of a fine broth, when there had been a knocking on the door.

“Announce me,” said Tata, spreading out her train, & Betty, who never gave herself airs, announc’d her. Betty’s husband soon arrived, enslav’d in an aura of awe as Tata put forth all her arts to dazzle the poor man into a certain sensual servility. It was at the very moment she was flicking a long rivulet of flowing auburn hair from one of her large & partially exposed breasts that a powerful groan of thunder, like Poseidon waking from slumber, erupted in the sky-chambers over Glasgow. With almost immediate effect there began to hurtle down one of those showers which had been recently spoiling so many hats, & bringing so many roses into bloom.

“Good gracious! How it’s coming down,” said Tata. “May I trouble you to let your maid fetch a taxi?”

This was the perfect moment for Betty’s husband to prove himself worthy of her adulation, for an honest man would have here said, “I haven’t a maid, this lovely vision is my wife.” Alas, the man, or half a man, was a coward, & replied, “certainly.” Twirling his thumbs, he went into the kitchen where Betty was now slicing her vegetables, with a rather sharp looking knife which her husband clearly couldn’t see, so blinded by the attractions of Tata had he become.

“Madame Tata,” he utter’d, “is wearing a satin gown & satin shoes. It is raining cats & dogs & it would be wonderful if you could…”

“Fetch her a cab,” ask’d Betty, giving her husband a flaming glance that ought to have made him sink directly into the earth. “Fetch a cab! Well I never ! Hold on a minute.”

Betty went outside, getting her only pair of boots soak’d right through to her stockings. Her eyes, once bright as the stars, were now dark as doom itself. Her husband had never even waited at the door with a towel or anything, the wake of which was a month-long pantomime of cold soups & warm beer. No more rosy slices of smok’d salmon, sausages, bacon, roast potatoes, pies & butter’d sprouts, all wash’d down with a fine whiskey & a bottle of Irish stout. Just cold soup & warm beer. Betty, who used to rise with the lark to attend the marital home, could now only be awoken with difficulty after eleven o’clock, murmuring, “surely its not daylight, yet.” The house, formerly so spotless that you could have sought a grain of dust in vain, resembl’d the aftermath of an errant tsunami as it pull’d back from some unsuspecting coastal village.

“Betty, its such a mess,” tutted her husband one day. “But I fetch’d the cab,” she replied, which pretty much form’d the refrain of all their future verbal engagements.

“You don’t love me anymore; you never kiss me.” “No, my dear, but I fetch’d the cab.”

Betty left her husband after a month, spent a year at her brothers at Shiskine, then got her own place not far away. Two decades of life later they were still in each other’s orbit & had evolv’d into fine bridge partners. Of this particular arrangement of players at the AVC – the Arran Vint Club as they quite proudly call’d themselves – Bobby Mentieth was, at first, especially displeas’d. He was annoy’d at always having to play with Archie Alexander, that is, in other words, to lose all hope of ever making a gand slam no trumps. In every way he & his partner were entirely unsuited. Archie was a weary, dried-up fellow, dress’d summer & winter in dark coat & trousers, & was always silent & severe. Without fail he would appear punctually at eight o clock, not a moment before or after, & straightwise take a pack of cards up in his fingers, one of which appendages was crown’d by an over-large diamond, set in a circlet of pure gold. What annoy’d Bobby the most in his partner, however, was that he refused to make a higher contract than four tricks, even if his hand was certainly worth more.

Polar oppositely Bobby always took risks, was a bad card holder & consequently a serial loser, but never losing heart, invariably hoping to win the very next time. Eventually, & relievingly for the siblings, the two mens’ styles soon melded efficiently enough, & they began to play rather well together, a reconciliation all who have felt the spirit of the tao could have easily predicted.

Two

The seasons pass’d on Arran as they always do – pleasurably. Meanwhile, in that ornate conservatory at Shiskine, the games of vint continued with the same enthusiasm as the very first hands they’d play’d. Outside, the doddering old world pursued its varied career; now red with blood, now drench’d with tears, now wrestling with worry; leaving in its track the groans of the sick, the naked & the wrong’d. Fascism was rising in Europe, while over in Manchuria the Japanese were running a deadly riot. Some faint suggestion of all this was sometimes brought in by Bobby Mentieth, but only as a distraction when he was late & came in to see the others already seated at table, fifty-two pink cards laid fanwise on the green cloth, & the tick-tock of the old clocks the loudest they’d ever tell the time.

Bobby, red-cheek’d & carrying the fresh air with him, hurriedly occupied his place across from Archie & said;

“It seems Hitler is about to enter the Rhineland.”

Betty consider’d it her duty as a co-hostess of sorts to notice the idiosyncrasies of her guests. Thus, while Archie gather’d in & shuffl’d the pack in grim silence, she alone answer’d.

“I’m sure the League of Nations will sort it out, but hadn’t we better start?” & so they began, slowly stepping into the silence of an undiscover’d Sumerian tomb, their conjoin’d breathing becoming the monetary equivalent of a fraction of a fraction of a farthing.

On & on they play’d. Twice a week in the spring, summer, autumn; thrice a week in winter. There were incidents, but chiefly of an amusing character. Sometimes Jock would forget altogether what his sister had said, & once, having contracted for five tricks, fail’d to make one. Bobby laugh’d loudly & magnified his loss, while Archie remark’d drily: “If you’d only gone four you’d have been nearer getting it.” Betty laugh’d, for it seem’d just for a moment Jock’s everfriendly grin, aflash with white even teeth, had spontaneously transmorph’d into a set of crooked ladders lying awkwardly against a wall.

Betty conceal’d her feelings best, but always display’d intense excitement when she contracted for slam. She grew a trembling red, not knowing which card to play, looking piteously at her taciturn brother, while her two opponents, with knightly courtesy for her womanhood & helplessness, encouraged her with condescending smiles, then waited patiently.

Generally speaking, however, they took the game very seriously. To this renegade, musketeering quartet the cards had long ceas’d to be mere inanimate objects. Each hand, & every card in that hand, had its own particular individuality, & lived its own life full of wishes, tastes, sympathies, & caprice. The cards always combined differently, & when commingling with each player’s personality added even more mind-boggling combinations to the possible procession of play. Forget Go, forget Chess, it was thro’ vint bridge at Shiskine that the mathematical universe could really unfurl its infinite tapestry.

Hearts usually went to Archie – Archie’s hearts they call’d them – while Betty’s hand was usually full of spades, tho’ she never lik’d them at all. Bobby always held bad hands. At times, for several evenings in succession, he could hold nothing but twos & threes, for which reason he was firmly convinced he would never make a grand slam, as the cards knew of his great aim & thwarted him on purpose. In the night-times following such desperately unlucky evenings, Bobby would fall asleep dreaming of winning a grand slam no trumps. So many times did this dream-desire manifest itself that it became the strongest wish of his life.

Other incidents happen’d, not immediately connected with cards. Archie crash’d his car into a deer on one occasion, leaving the bonnet thoroughly damaged, forcing his son to drive him to Shiskine. Then, Bobby disappear’d for two whole weeks, & the AVC didn’t know what to do at all; three-handed vint was contrary to their habit & turn’d out to be rather boring indeed. When Bobby return’d safely, his red face, which had shown up so vividly against his scanty white locks, had grown pale, & he seem’d to have shrunk. He inform’d them that his son had been arrested for some offence & was currently in prison in Fife. All were astonish’d, for they never even knew he had a son: perhaps he had mention’d it some time or other, but they had forgotten all about it. Soon afterwards he again fail’d to appear, & upon the Saturday when they were accustom’d to play for longer. They were also astonish’d to discover that Bobby had suffer’d from angina thro’ all these seasons of serious cardplay, & that he had suffer’d a severe attack that Saturday morning. But afterwards all went on as before, & the game became even more serious & interesting as Bobby regal’d them less & less with topics of the outside world.

Last Thursday, however, there was a startling change!

Three

As soon as the game began last Thursday, Bobby Mentieth made a contract of five, & won not only his contract but a small slam, as Archie had an ace & kept quiet about it. For some time after Bobby held his usual cards, but then started a series of good cards in suits, as if the cards themselves wish’d to see how pleas’d he would be. Then he bid to play for the game, & all were astonish’d, even the phlegmatic Archibald Alexander. The excitement of seeing the furious tremblings of his partner’s chubby fingers infected him & all the other players.

“What’s up with you today?” huff’d the gloomy Jock MacKinley, who fear’d somebody else’s good luck was the precursor of the next level of his own life’s misfortunes. On the other hand his sister was delighted to think that Bobby was doing rather well for once, & curtly responded, “the cards must give everyone a turn!”

After Jock dealt the next hand, Bobby pick’d up his thirteen cards. Fanning them out slowly, his heart almost stopp’d beating & a sylvan mist rose before his eyes – he held twelve certain tricks in his hand: the clubs & hearts from ace to ten, the ace & king of diamonds. If only he could pick up the ace of spades in the exchange he had the grand slam no trumps.

“Two no trumps,” he began, controlling his voice with difficulty.

“Three spades,” said Betty, who was almost as excited, having nearly all the spades from the king downwards.

“Four hearts,” retorted Archie with a queer curl of an upper right lip never seen before at that most traditionally sedate of tables. He could sense something was brewing. Bobby promptly declar’d small slam, but Betty, carried away on a lavaburst of Vesuvian enthusiasm, bid grand slam in spades, despite seeing she could not make it. Bobby reflected for a moment, & affecting an air of triumph to conceal his agitation, declar’d, “Grand slam no trumps.”

Bobby Montieth declaring grand slam no trumps ! All were astonish’d, with Jock MacKinley exclaiming a loud & almost caterwauling:

“OH!”

Bobby stretch’d out his hand to draw the clinching, cosmic card, but sway’d at the final fingerstretch, paus’d a moment, lay his cards on the table, fell slowly to the left & sprawl’d in a heap across an oriental rug.

When the doctor arriv’d he found that Bobby had died from heart failure, &, by way of comforting the living, added a few words on the painlessness of his death. They placed the cold, dead, dumb man on a sofa in the conservatory, the one Jock would sit on with a book & the wireless, watching black stormclouds burst over Kintyre. Bobby was cover’d by a sheet & look’d large, fearful & unlov’d. Close by, the card table had not been yet clear’d, & Bobby’s cards lay face down in the same neat pile that he had assembl’d during the last ever act of his energized being.

Archie walk’d round the room with small uncertain steps, trying not to look at the corpse, or go off the rug onto the polish’d floorboards, where his heels made a nerve-racking noise. After passing the card table several times he at last gave in to the gods of curiosity & studied his partner’s final hand. Then, placing them down in almost the exact neat pile as he had found them, he overturn’d the card Bobby would have drawn. It was the ace of spades, which would have made the grand slam. Archie sped off, heavy heels now clattering over hardwood, & in the next room sat down & wept, because this dead man’s fate appear’d to him the most pitiable of kinds.

Just as in many of those similar moments of extreme pathos experienc’d throughout Humanity’s tragic existence, Archie remember’d a classical quote to somehow make sense of things. A leaf from the Odyssey issued forth from his mind’s internal library, exclaiming, ‘all deaths are hateful to miserable mortals, but the most pitiable death of all is to starve.’ But Homer had existed long before Bridge had been invented, & shutting his eyes Archie began to picture the sheer delight glowing & growing over Bobby’s face as he saw that ace of spades. That he never did so far outwoes a starving being, who would have at least at some point in their lives gorged with all their mortal senses upon the colours, aromas & flavours of multiple different foods.

On a seat by the window, the events of the evening pass’d in review before Betty, beginning with the five diamonds which the deceas’d had won & ending with a series of good cards so exceptional as to be ominous. Now here, just a few feet away, lay Bobby Mentieth, dead on the very verge of an incredible grand slam. ‘How irrational, how terrible, & ultimately how unavoidable, is deathk,’ she thought. ‘Just one more moment of life & he would have seen the ace of spades, but he was dead without ever knowing.’

“Ne-ver,” she whisper’d out loud, pronouncing each syllable slowly, which allow’d the word to to be laced with a taste of bitter regret.

Archie shuffl’d back into the conservatory, aware once more of his clattering heels, & had decided to play his partner’s final hand, picking up the tricks one by one until he reach’d thirteen. It was the first & last time that he ever went more than his contract of four, & won the grand slam in the name of friendship.

Mrs Robertson

One

Memories swarmed into Mrs Robertson’s mind like prowling wildcats; days of youth & drain’d promise, nights of wonder & haranguing melancholy. Life’s toleraby engaging carousel.

‘What have I achiev’d?’ she ask’d herself. ‘Indeed, what was there to achieve?’

She remember’d her village under the mountain; the sad, sad parting from her parents those two summers since; & the hard days of service that follow’d. Memories drew talons, clawing her young psyche with jagged slashes, which she shrugg’d off, somehow, one-by-one, despite the wincing pain.

Yet, here she was, a young English bride, sunny-haired & hopeful-eyed, with lips that slowly parted before she smiled, making strangers want to kiss them. One of these, of course, had been Mr Robertson, her recently acquired brand-new husband, & the only one of the random admirers who – following the aforementioned smile & its glorious aftermath, when the softest regions of her face broke out into attendant dimples – had dared to ask her name. Ever since, in similar circumstances, lest anybody should think that this smile which fluttered like a handkerchief dropped into a Roman fountain was meant for them, she would quickly look up for her dear Charles – who was a foot taller or so – to find him tenderly reciprocating her glance of love with a gaze of golden adoration.

“I wish I could meet your parents,” he had said on of these occasions, completely out of the blue. “I’m sorry darling if that sounds selfish, but they must be very special people to have created such a treasure trove as you.”

“One day you will,” she replied, not knowing then that she would refuse to even invite them to her wedding. “Auld grievances,” she had cited, without giving a single iota of detail. The only thing she ever really told Charles about them was that, despite all the young men in her mountain village vieing for her mother’s hand, her mother had only ever wanted her father. “Such loyalty, such monamour,” she assured Charles, “was the definitive streak running thro’ the females of my family.”

Many people thought Charles was her brother, so similar were their thick flossy hair & rabbit bimbling eyes. They had little money between them, but the highest of hopes that one day they would be well-off enough to never have to worry about money & its rat race acquisition. A couple of well-paying pension plans & lots of scuttling grandchildren to spend them on were hardly Olympian ambitions; but to a young couple deeply entrenched in each other & in love, there flew dozens of golden eagles soaring through the misty gullies of their living dreams.

Charles had recently got an agricultural job among the epic & fertile plains of Aberdeenshire – auld farmtoun country – where he had obtain’d a friendly impression of everybody & much public trust in his own abilities. His boss had given him a couple of weeks leave to celebrate both his coming of age at one & twenty & his marriage to his younger wife.

“It must be Arran,” he had said while discussing potential honeymoons, “I went as a student & simply had the best of times! Akuta same…”

“What!” demanded Abigail.

“O sorry, akuta same, it means ‘deadly shark’ in Japanese. My classmate at the time had taught me the phrase on the ferry as we cross’d once to Arran. I will remember it always.”

Mrs Abigail Robertson found herself on that very same ferry, perched on a Calmac deck one gusty but sunny day, swiftly steaming west, with the boat being chas’d by three playful gulls. As the seabreeze made a rustle like rich raiment, or the whispering gossip of inquisitive neighbours, Charles stepp’d back from the rail & took a seat in those identical wooden chairs so beloved by the Calmac ferry company.

“I’ll be with you in a minute darling,” smiled Abigail who, heady as a hedonist in heaven, peer’d forwards towards the haunch’d Isle of Arran, widening steadily towards the west.

Altho’ Charles was only one & twenty, & she barely eighteen, to her he appeared almost godlike in his age, a piramid of maturity built up in some wise, old epoch of time. Her own life seem’d as simple as it had been short. She only could remember being a little girl, & then the next thing that occur’d was Charles Robertson, & positively the next thing she remembered of importance was being Mrs Charles Robertson. Her later adolescence & those two years in service were nothing now but grassy dewdrops dissipating in the morning sun. The one thing that never left her mind, however, was the mountain which towered above her village in the Lake District of England. Its beauty had been preserved by those who care the most about preserving beauty. Wordsworth had prevented rail companies sending steaming chains of dragon carriages down the unpolluted valleys. Her grandfather had also beat back the sniffing scouts of coal, mineral & timber companies, all wishing to skin & gut their forested mountain like a skillfully hunted piece of game. He had also said that her love for Charles was her love of a baby, & then but a baby in love. He had opined as much on a visit Scotland to ostensibly meet his potential grandson-in-law, but really because he loved to fish, & to his own mind the rivers which flow’d from the Cairngorms were the richest of all.

All this, of course, was five & forty years ago, for you know how old Abigail was when she returned to Arran last summer? Three & sixty!

Part Two

Five & forty years ago, as I was saying, Abigail Robertson was exacting, with some excitement, her first visual memories of the mountains of north Arran, where Goat Fell points at the adventurous spirit with a rocky & beckoning finger, saying, ‘climb me.’ After landing at the port of Brodick, Mr & Mrs Robertson of Rhynie Farm Cottages, Rhynie, Aberdeenshire, were seated in the back of a primitive, yet efficient taxi. They travelled at a gentle speed for six miles, following the coastal road as far as the sprawling ribbon-village of Corrie, decamping for a week up front in its bustling hotel. Their room overlooked the sea, & they made love the very moment the maid had closed the door behind her. The five shilling tip thrust into her hand by an excitable Mr Robertson had ensured her rapid exit.

With a bridal veil thrown over her neck & bosom, & her fine bright tresses carelessly yet gracefully arranged, she appeared to the eyes of her enchanted lover rather like a vision than a creature of mortal beauty; altho a countenance of nervousness would accompany her first kisses as a man & wife alone. The sweetness & the ecstasy of those moments would penetrate Abigail’s waking moments for an entire lifetime, & hearing the whispering breath of Charles’ vows once more in her ear, would echo just as long. Then came the puzzle-dance of passion, awaiting the moment when all the protuding pieces fitted together in the lock of love – limbs with limbs, eyes with eyes. It was a moment such as happens with only the truest of soul mates. All the different versions of themselves from across the aeons of human existence, reuniting in lovemaking for the first time as those particular avatars, were in that room, fractured facets of divinity form’d by their own recognizable shapes.

The newlyweds arose in the finest of spirits, as golden as the summer sun which had enticed a family of seals onto the rocks by Corrie harbour, to silently bathe in those sweet & splendid rays. Abigail had pointed them out to her husband as they walked the half mile south to the whitewashed cottages of High Corrie, perched sporadically above the sea like a Tuscan hilltown. Beyond High Corrie lay the mountains of Arran, where one hour later, Charles Robertson, veering from the paths with the elation of consummated love, had leapt onto a pile of brush which covered a long forgotten pothole, & vanished utterly from the earth.

It took everything for the good people of Corrie to contain Mrs Robertson in her grief. A couple had to stop her wading into the sea, her pockets full of heavy round stones. Another had to find her grandfather in England, for he was the only person Abigail wanted to see. The Hotel manager had encouraged the matter, for it seemed that after three weeks Mrs Robertson was rapidly running out of money, but was still obstinately refusing to leave. Each day she would retrace the steps she had made on that most magical of mornings, remembering the laughter, the chatter & those beauty spot embraces, strung like a pearl necklace over the mountainsides of Arran. Then, at the pothole’s mouth – fenced off now, for safety – she would sit, tearless, day after day, in whatever manifold variety of weather, simply staring into the profundity of the planet’s undercrust. Even by the onset of the Autumn storms, no power could win her from the place whence her Charles had gone.

Every effort was made to find him, but alas, in those days, pitcaving techniques were very much in their rudimentary infancy. Specialized equipment like nylon kernmantle rope, & specialist methods such as Single Rope Technique were decades away. The deepest they had got was 20 ft down, where a sharp-angl’d ledge would have bundl’d Charles into the black darkness of the mountain’s internal chambers. It was deem’d too dangerous to attempt any further probing, & the matter was deem’d closed. If there was a time worse for her than the moment her husband dissappeared, it was the one when they told her his body would never be found.

Three

Mrs Robertson went back to her little cottage near Rhynie & lived there for the rest of her days. The rooms of the cottage that was to be their home remained bare & unadorned, as Charles had seen them last. She could not bring herself to alter them in any way, just in case he ever came back. She knew he would never, but unresolved grief is a far greater mind monkey than grief itself. If only he had been buried in a nice Scottish kirkyard, under the sweetest air of the northern climes, some green place lying open to the sun, where she could go & scatter flowers on his grave, where she could sit & look forward amid her tears to the time when she would lie side by side with him – they would be seperated only by short life, but united for eternity. Now, it seemed, that unless she returned to the island of all her woes – a thought which made her recoil as if seeing a scorpion primed at her feet – they would remain apart forever.

For Mrs Robertson, her life had become tainted with the taste of shame. Charles had been beloved in his community, his family adored him, & now he was gone. The young English siren had lured him to his doom on the jagged rocks of the Clyde. But Abigail was a stoic lass & did the best she could; working in service, then opening a little shop once she’d saved up enough money. Of course she never remarried, how could she? The ambrosial memories of her honeymoon night could never be desecrated by lieing with another man. There was much interest of course, a veritable Penelope surrounded by suitors, but no man could ever win so much as a courteous half-smile, let alone alone one resembling that which had won, for her, dear Charles.

It was early in the last spring that Mrs Robertson received a letter from Arran. It was penn’d by a young man who, with a quaint & polite formalism, had offer’d to find her Charles. The wind-blown hollow of her heart suddenly gush’d with roseate blood, straining to burst out of her chest. It took two cups of tea, a small glass of sweet sherry & a phone call to her best friend to finally finish off the letter. It went on to explain how the young man’s name was Connor Syme, he had been a student of Geology at St Andrews, that he was a passionate explorer of cave systems, & that he thought he had obtained the right & proper modern equipment to find her Charles.

After five & forty years Mrs Robertson suddenly found the will to live, & to live life for as long as possible. That her beloved Charles might be afforded a proper burial near their little cottage energized every effort of her being to beautify their little home. The trifling articles, curiosities & pictures she had bought with Charles on their honeymoon were finally brought out. She would ask how such & such a thing look’d, turning her pretty head to some kind visitor, as she ranged them on the walls. Now & then she would have to lay the picture down & cry a little, silently, as she remembered where Charles had told her it would look best. She felt him with her in each room as she furnish’d them to the plans they had made in their minds, hand-in-hand on the curved beach of Ardrossan, as they gazed across to Arran in love. One room she never went into; the one they had meant to have for the nursery. It is not that she never imagin’d children in there, however, for often times curly headed cherubs that look’d just like Charles did clutter her cottage’s hearth & hall.

Two weeks later Mrs Robertson was back on Arran for the first time in almost half a century. She had alter’d very much in that time, but was fill’d with a spirit quite unchang’d from that which energized her honeymoon.

“This is a good day to be alive,” she said to herself, “no, every day is a good day to be alive, this is a much better day to be alive.”

With difficulty temper’d by determination she climb’d the same steep paths she had once worn to the bedrock in those terrible weeks of limbo following her husband’s disappearance. The pothole was still safely secured; the sign was as bright as ever, but the fences had been worn to crumbling pastel cadavers in the wake of countless Atlantic storms.

She watch’d on in silence as Connor & his small team open’d up the pothole & scrambl’d into the claustraphobic core of the mountain. An hour or so later, Connor haul’d himself out of the inky blackness & with a beaming smile said, “we’ve found him.” It took several minutes for Mrs Robertson to finally stem the oceanic floods of tears which had well’d up from the wasted grieflands of her soul. But slow the flow certainly did, & in the silence between her subsequent & intermittent sobs, Connor spoke again.

“I think it best, Mrs Robertson, that you do not see the skeletal remains, unless of of course you really wanted to, but I do advise against it. However, by some miracle of dry air, your husband’s jacket has been completely preserv’d, if a little dusty. Would you like to see it?”

Thes were the happiest moments in the later life of Abigail Robertson of Rhynie Farm Cottages, Rhynie, Aberdeenshire, & within a week the jacket was hanging in the once unused nursery in their cottage, perfectly clean & pinn’d to the wall besides her own bridal gown, which she never once thought to throw away. She loved just sitting in the room with a small peat fire burning, & to simply remember.

Her husband’s funeral had been more of a celebration of life than a memorial to death. Relations of his she had never seen of every generation had attended, with a couple of his nephews coming from as far away as Canada. Once all the family fuss had died down, she would attend daily to his grave; fresh flowers once a week, a wee prune of the rose brush & a gaze at the turf beside him where one day they would be truly reunited.

This dream of hers was not even disturbed by that singular strange evening when, of a sudden, she felt a compulsary tugging at her psyche while sitting in the nursery turn’d bridal shrine. ‘What was in the jacket pocket,’ she began to enquire with some force. It turn’d out there had been something in his pocket – a letter, adressed to a certain Albert Alexander of Dippen Farm, Arran. Of course she open’d it, & was intrigued by the Japanese characters at the head of the page. It was clearly her husband’s handwriting, & she began to read;

Dear Albert

I long to see you

I have married a young woman. She is good for me. But she is not you. We are staying in the Corrie Hotel for a week. Please come & take a room where we can meet &…

Mrs Robertson suddenly cut the reading short, & with the slow & deliberate motion of those dutiful wives who keep their husband’s secrets, as the letter was toss’d into the fire the fine wine memories of her darling Charles were tenderly, & forever, preserved.

Essay Upon The Second Ballad Revival

A poet sat in his antique room

His lamp the valley king’d

‘Neath dry crusts of dead tongues he found

Truth, fresh & golden-winged

Alexander Smith

All poetical revivals begin with a spark, from which a fire storm blows through the cobwebs of an age. For the Second Ballad Revival it begins with the island of Arran & of course an arrival of a literary-minded man – that man being me. Any writer worth his or her salt who comes to Arran for any sustain’d length of time, feel they should write a book about this glorious new island they have discovered. Its that inspirational a place. The thing is, everything that needs to be said about Arran has already been said by scores of times by some very excellent authors. What I needed was an angle.

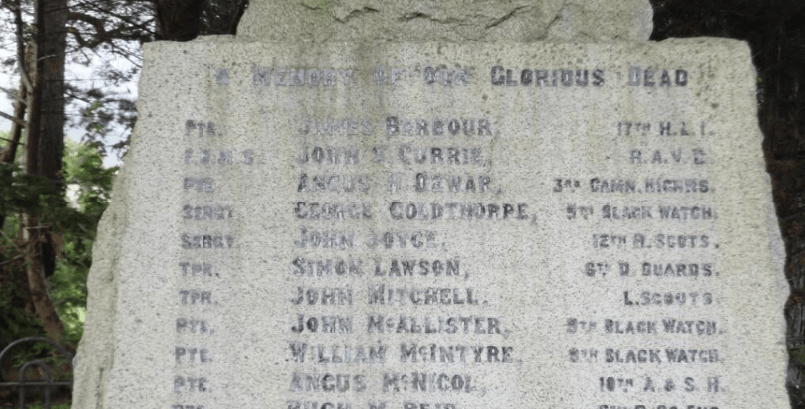

It came at me like a pair of crab-like pincers, manifesting as a Great War Memorial & an old book. The former is in Brodick, the capital of Arran, while the latter concerns some of the names upon that memorial – Brodick-Arran & The Great War by James Inglis (1919). One day in idle mode I decided to match some of the names on the memorial to those in the book. I spent a few moments looking up at the monument, then down at the page, then back up again until & I was struck saddened & also excited as a Bardic storyteller to discover that three Black Watch soldiers who worked together at Brodick Castle, enlisted in the Black Watch on the same day, & died together on the same day at the Battle of Loos, September 25th 1914.

This materielle transcended even Shakespeare, a spark fit enough to begin a poetical revival, but in what form? A friend of mine was visiting Arran with a vernal interest in the art of poetry, so I ask’d him to read the Rime of the Ancient Mariner entire. A wonderful experience to listen to, my psyche began to overbrim with poesis & within a day or two THE BALLAD OF BLACK WATCH BRODICK was straining for existence like an animal slouching ‘towards Bethlehem to be born.’ At this point I had my matter & my mould, & being an epic poet by trade, & the matter so elongated, I knew that only a grand ballad cycle would be sufficient to answer this particular call of the muse.

It can be fairly said that in this third decade of the third Millennium (AD), poets no longer write for Humanity, as has been their ancient wont, but compose only to please themselves & other poets. A clique has surrounded the art, upheld quasi-religiously by its proponents, encasing poetry in a dull concrete, from which parapets they observe uncommenting the decline of poetical appreciation among the general population. There can only be one possible remedy for this puritan assault on the art, & that is the reintroduction of the ballad form – the poetry of the people. Within its simple tuneful strains & anthrosociological narratives a poet may place the moral foundations of a people. “I knew a very wise man” reports Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun (1655-1716), “who believed if a man were permitted to make all the ballads, he need not care who should make the laws of a nation.”

There is a beautiful truth in balladry which taps into the human pond of past lives & conduct. These simple looking structures resonate a complex record of the actions of humanity, detailing in narrative form events relating to society through individuality. Ballads are also those songs & rhymes which awaken the earliest poetical appreciations in all of us. As the poet thunders through four-line stanzas of distich & rhyme, the reader or hearer will instantly feel that they are in the presence of poetry, proper poetry, the same poetry which pentrated their psyches in their infant malleability, & nurtured through childhood. In utterance lyrical, sharp & decisive, they are the truest test of a poet, because ultimate raison d’etre is to please. To teach comes a close second, & thus a ballad done well can transcend even the most elite of educatory lecture halls in a language accessible to all.

Send in the artists, mystics and clowns. Their fertile imagination pours the new wine of the gospel into fresh wineskins. With fresh language, poetic vision and striking symbols they express God’s inexpressible word in artistic forms that are charged with the power of God, engaging our minds and stirring our hearts as they flare and flame.

Brennan Manning: Ruthless Trust

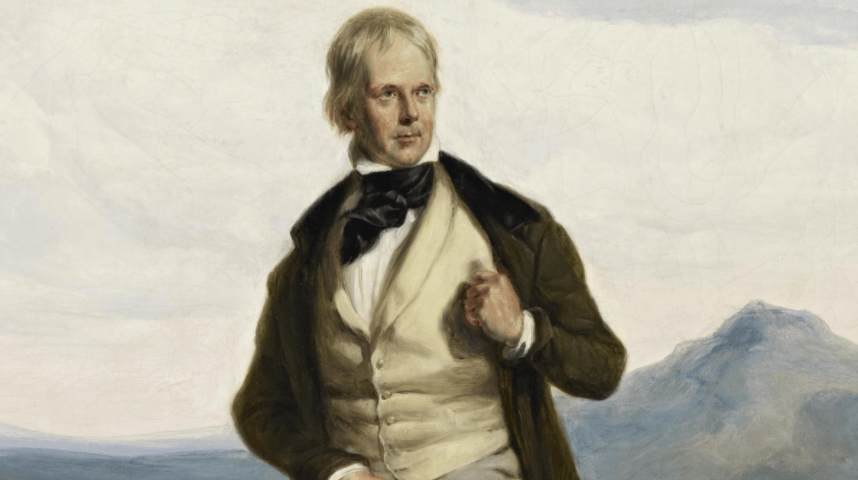

Thus, with BLACK WATCH BRODICK I would like to announce the arrival of the Second Ballad Revival. The ‘first’ took place during the Romantic Age, beginning with Thomas Percy’s ‘Reliques of Ancient English Poetry’ (1765), evolving moderistically with the songs of William Blake & Rabbie Burns, a process that continued with the Lyrical Ballads of Wordsworth & Coleridge, La Belle Dame Sans Merci of Keats, & concluded with the assembling of the Scottish & Border ballads by Sir Walter Scott, publish’d & revised between 1802 & 1830. Scott was an immense & dedicated balladeer, & his Essay On The Imitations Of The Ancient Ballad (1830) contains interesting reflections on the form which contain the mantras of the First Ballad Revival. This short extract tells the story of the Ballad Form up until the dawn of the Romantic Age.

The invention of printing necessarily occasioned the downfall of the Order of Minstrels, already reduced to contempt by their own bad habits, by the disrepute attached to their profession, and by the laws calculated to repress their licence. When the Metrical Romances were very many of them in the hands of every one, the occupation of those who made their living by reciting them was in some degree abolished, and the minstrels either disappeared altogether, or sunk into mere musicians, whose utmost acquaintance with poetry was being able to sing a ballad.

The taste for popular poetry did not decay with the class of men by whom it had been for some generations practised and preserved. Not only did the simple old ballads retain their ground, though circulated by the new art of printing, instead of being preserved by recitation; but in the Garlands, and similar collections for general sale, the authors aimed at a more ornamental and regular style of poetry than had been attempted by the old minstrels, whose composition, if not extemporaneous, was seldom committed to writing,

In England, accordingly, the popular ballad fell into contempt during the seventeenth century; and although in remote counties its inspiration was occasionally the source of a few verses, it seems to have become almost entirely obsolete in the capital. Even the Civil Wars, which gave so much occasion for poetry, produced rather song and satire, than the ballad or popular epic.

In Scotland, on the contrary, the old minstrel ballad long continued to preserve its popularity. Even the last contests of Jacobitism were recited with great vigour in ballads of the time, the authors of some of which are known and remembered.

On the whole, however, the ancient Heroic ballad, as it was called, seemed to be fast declining among the more enlightened and literary part of both countries; and if retained by the lower classes in Scotland, it had in England ceased to exist, or degenerated into doggerel of the last degree of vileness.

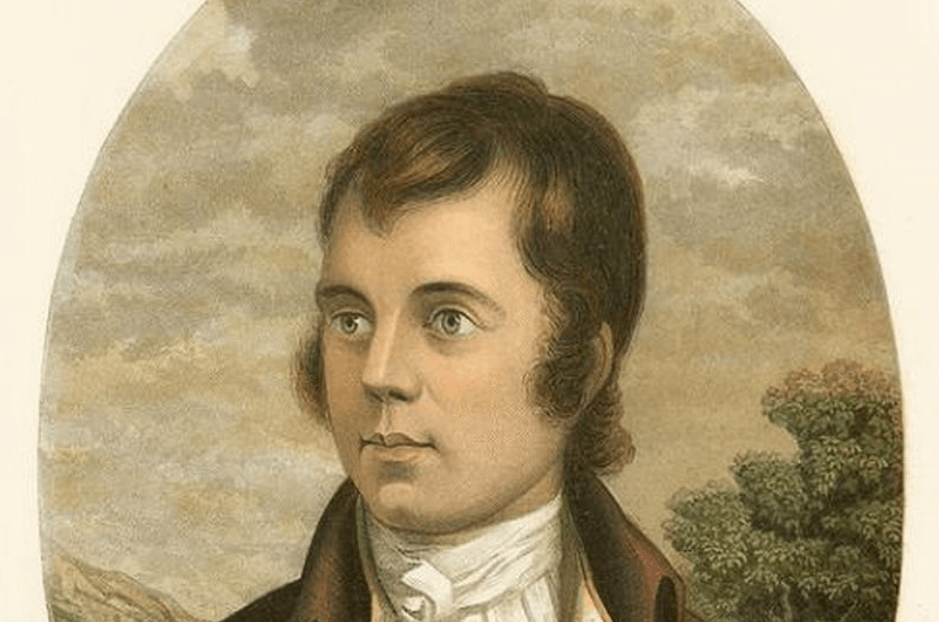

The same can really be said about the ballad from in the 21st century. No performance poet would chaunt in the old style, no poetic publisher would stoop so low as a broadsheet, but I am feel in my very bones that society of the my day is ripe for a balladic renaissance. Perhaps there is something about living in Scotland that is inspiring me on a metaphysical level. As Scott says, while the ballad was dying in England, it still thriv’d in the Scottish hinterlands. In my 17 years domicile in Scotland, I have understood that the keeping of tradition has been woven with steel & deeply ingrain’d into the native fabric. Robert Burns records the animus & his personal connection with the Scottish balladeers.

There is a noble sublimity, a heart-melting tenderness, in some of our ancient ballads, which show them to be the work of a masterly hand: and it has often given me many a heart-ache to reflect that such glorious old bards—bards who very probably owed all their talents to native genius, yet have described the exploits of heroes, the pangs of disappointment, and the meltings of love, with such fine strokes of nature—that their very names (O how mortifying to a bard’s vanity!) are now “buried among the wreck of things which were.”

O ye illustrious names unknown! who could feel so strongly and describe so well: the last, the meanest of the muses’ train—one who, though far inferior to your flights, yet eyes your path, and with trembling wing would sometimes soar after you—a poor rustic bard unknown, pays this sympathetic pang to your memory! Some of you tell us, with all the charms of verse, that you have been unfortunate in the world—unfortunate in love: he, too, has felt the loss of his little fortune, the loss of friends, and, worse than all, the loss of the woman he adored. Like you, all his consolation was his muse: she taught him in rustic measures to complain. Happy could he have done it with your strength of imagination and flow of verse! May the turf lie lightly on your bones! and may you now enjoy that solace and rest which this world rarely gives to the heart tuned to all the feelings of poesy and love!

I shall finish my personal manifesto to a Second Balladic Revival with the essay of Scott previoulsy examined. Within its corpus there has been etch’d a wonderful passage which perfectly reflects the painted corner in which poetry has found itself in this our own age; ‘The realms of Parnassus, like many a kingdom at the period, seemed to lie open to the first bold invader, whether he should be a daring usurper, or could show a legitimate title of sovereignty.‘ It is daring to be a balladeer in the 21st century; it is sovereign to be an epic poet; & the realms of Parnassus have become pixels on an instagram post. It is time to bring poetry back to the masses, an enteprise worth composing for. For that I will need orators, rhapsodic singers if you will, in the tradition of the Homeric reciters of Pisistratan Athens. For them I leave the L’Amfiparnasso of my new poem.

TO MY RHAPSODES

To all ye glorious storytellers

Who sing in the Saxon tongue

Bring the wine up from the cellars

Pass the clinking glass among

When claret good oerbrims the cups

& company comes keen

Mount up the Hippogriff that sups

From blissful Hippocrene

Then with a clear & poignant voice

Go sing my ballad cycle

Leaving your company no choice

But to finish the recital

There’s twenty-seven cantos worth

Of twenty-seven stanzas

Awaiting dutiful rebirth

In ring’d extravaganzas

All born in mine hybrid accent

A maze of burrs & measures

But structure in each consonant

& in the vowels treasures

There’s Edinburgh, there’s Bournemouth Beach

There’s Burnley & there’s Venice

There’s mood & meaning in my speech

There’s beauty & there’s menace

There’s murder, bloody murder, too,

There’s loving & there’s grieving

There’s scenes that set the eyes adew

When gentle goes thy weaving

For thou art Rhapsode, & thine art

Will stich auld songs together –

So choose which cantos to impart

Goose quilt or just a feather

BBWB 6: The Budapest Cup

THE BALLAD OF BLACK WATCH BRODICK

CANTO 6

The Budapest Cup

21-5-1914

Celtic FC 1 – Burnley FC 1

Budapest

Ulloi Uti Stadion (Ferencvaros)

Attendance 10.000

Burnley: Dawson, Bamford, Taylor, Halley, Boyle, Watson, Nesbitt, Lindley, Freeman, Hodgson Grice.

Celtic: Shaw, McGregor, Dodds, Youngs, Johnstone, McMaster, McAtee, Gallagher, McColl, McMenemy, Browning.

O! to be a buzzy Burnley boy

Leaving the Crystal Palace

With loads of Scousers to annoy

As cocky as a phallus

For down the Royal Capital

Burnley’s beat Liverpool

A victory to catapult

Their statuses to cool

Stratospheric Olympians

Invited to renew

Tests of the best Hungarians

Austrians, Germans too

As have that famous football club

Supremely catalytic

Team colours daubing home & club

Ardent for Glasow Celtic

Platoon of hoop-green Bhoys & men

Ninth national title win

Up raise the cup, the league makes ten

The Double’s soak’d in gin

So off they went by train & port

To Europe’s heaving heart

The best of British to promote

With skill, with style, with art

As Burnley won the Berlin game

Celtic play’d Ferencvaros

& won two-one, the scoreline same

For Clarets, who now cross

The border into Hungary

Where they quickly caught the catch

They were not to play a friendly

Against Celtic, but a match!

Whose victors would be duly crown’d

Champions of the planet

A tall, gem-studded cup was found

& proper refs to man it

The day was hot, the Danube spun

A gust across the stands

Of Ulloi Uti Stadion

As players all shake hands

The anthem plays, the whistle blows

Firm tackles flew in thickly

McGregor gets a bloody nose

The needle sharpens prickly

The Celtic get the upperhand

The wind & sun behind ‘em

Thro’ Claret lines the forwards fann’d

Found passes meant to find ‘em

A penalty! Celtic shoot sweet,

Lancastrians retreated

Into a huddle, “Play to feet!”

Sweat urgently secreted

Saw battle surge on bare a blade

The pitch was baked unsodden

Like Stirling Bridge the Scot’s blockade

Like Flodden & Culloden

The Thistle & the Thorny Rose

Make war about a ball

When Saxon stridence for the cause

Bounc’d off a schiltron wall

The ball did swing from end to end

The crowd did cheer & yell

As reckless tackles fly, upend

Men crying as they fell

The Bhoys hung on until half-time

The crowd enthusiastic

The whistle blows, to cheers achime

The match renews fantastic

A handsome soldier in the crowd

Felt grim foreshadowings

Saw how each Briton fought full proud,

‘If ever,’ he thought, ‘fate brings

Our empires into open war

Pandora’s Box of pities

For tigers pace their island shore

& lions patrol their cities…’

A penalty, how Tommy Boyle

So slickly equalises

The temp’rature begins to boil

The heat of battle rises

The Burnley lads were now on top

All out attack, no cautions

Their play restrain’d, a train sweatshop

Will’d on with loud exhortions

As Trojans held the Scaean gate

As Spartans guard the Hot Springs

Attacks push’d back without abate

Crosses stream in from both wings

Both sides began to argue more

While cool heads on the sidelines

Shouted “its football lads, not war!”

Glory ignores all guidelines

& from rough tackle resolute

Celtic explode in numbers

McMaster pass’d a ball to shoot

By tired defenders’ slumbers

But Jerry Dawson palms away

That shot by McAtee

Burt Freeman winces as his day

Saved from calamity

A whistle blows, the ninety done

“Another thirty!” Burnley cries

But Scots & European sun

Cattle rattl’d by gadfly

Nobody won, nobody lost,

Thro’ handshakes grappl’d firmly,

The replay call’d, the pengő toss’d,

The next one’s set for Burnley…

BBWB 5: Suffragettes

THE BALLAD OF BLACK WATCH BRODICK

CANTO 5

Suffragettes

This was a most ‘immoral’ age

Dancing new-fangl’d tangos

Eliza swearing on the stage

Catwalks of risque clothes

An age it was of civil strife

Trade Unions upstirring

As strikes in every walk of life

Halts empire’s engines’ whirring

& bless the brazen Suffragette

That patriarchy smothers

“We’ll all get to the hustings yet

We sisters, sweethearts, mothers!”

Among whose thriving militants

Stands Sarah Fullarton

Emitting clear omnipotence

Until the vote is won

She was the fairest e’er to walk

The fragrant curves of Brodick

A lily on a fillystalk

But ‘tricky’ as a chopstick

For in an age of man & wife

When wives were more like servants

She’s chose to forge a finer life

‘Spite disapproving parents

In Glasgow there’s a rally sworn

All in Saint Andrew’s Hall

From Brodick, by swift steamer borne,

She’ll answer Pankhurst’s call.

Where if the Police did barge inside

Misusing all their powers

The speaker’s platform fortified

With barbwire mask’d by flowers

The room erupts, queen Emmeline

Captures the room starstatur’d

This is the season aquiline

When hearts by reason raptur’d

“Good morning sisters of the world

For future time each fights

When every little new-born girl

Shall share her brother’s rights

My promise kept, I’m here my friends

Despite our Kingship’s serpentin’d

Government’s inord’nate spends

To silence womenkind

But wit and ingenuities

Of women overcome such

Disgraceful elitist committees

That jaded aegis clutch

& come the change to surely come

That only time hold’s back

We’ll bang the democratic drum

Out of the cul-de-sac

Of our dead nation that ignores

The honest protestations

Of women knocking at all doors

Of legal delegations

Archbishops and the King himself

Dismisses each petition

Places them unread on a shelf

& calls its text sedition

How can one assume seditious

Equality twyx sexes

& socio-political justice –

Instead they avoid or vex us!”

With angry shouts & whistle blows

A storm of surging policemen

Surge thro’ the hall, a pure storm rose

Of women fighting men

Towards the stage the Police advance

With batons drawn for battles

Hail-dodging in a weird wardance

Chairs, boxes, buckets, bottles

A confus’d scene of bloody streams

& violence erupted,

The reckoning of dark regimes

By wickedness corrupted

A tornado’s worth of odium

All round the stage congeal’d

The Policemen reach the podium

Paus’d by barb’d wires conceal’d

Then stabbing pincers crab on crab

Hands lunge at Emmeline

Men drag her to a waiting cab

Some shameful concubine

She’s tossed inside a mouldy cell

Refuses bread & water

For you she’s done it, damoiselle,

For your mother & your daughter

All night the hungerstrike she kept

In noble spirit springing

Erewhile the streets of Glasgow slept

The Suffragettes were singing

Next morning she was roughly strapp’d

To stretcher & then driven

To Central Station, how they clapp’d

Those women who had striven

To line the route from cell to rail

Conjoin’d in common chorus

A movement that must never fail

Against the dinosaurus

That is the patriarchal beast

As down to Holloway

Goes Mrs Pankhurst whose increas’d

Her cause that awful day

When politics & ministers

Spurn basic Human Rights

& sends in strong-arm sinisters

Those ant-farm saprophytes!

BBWB 1: A Game Of Shinty

THE BALLAD OF BLACK WATCH BRODICK

CANTO 1

A Game Of Shinty

Hangovers rage on New Year’s Day

The air was ice & minty

As men & boys step out to play

The anycent game of shinty

They say King Fergus fetch’d the game,

At first, to Dalriada

That sets the Haelan brain aflame

‘Come on lads, hit it harder!’

Auld Scotia’s sport still grandstand mann’d

That thrill’d the Border Reiver

& on St Kilda’s rocky strand

They’ve play’d it with a fever

Down to the shore, from hill & dale

Roll players from the district

Descending on a sliding scale

The better twelves were pick’d

The captains were twa boyhood friends

Dol Homish & Laird Broon,

Who with a keen & convex lens

Their final teams fine tune

Jock Russel’s cheeks were red & ripe

The Dewar boys were freezing

& Sandy Fraser smok’d a pipe

Like whalesong was his wheezing

With ‘Bualomort’ & ‘Lecamlet’

The twenty-four were chosen

The rest slunk off, when pitchside set

They’ll spend the morning frozen

The goals erected on the plain

The level green beside

The bonnie sandsweep of Strabane

That kisses sea-green Clyde

It was the annual contest

Twyx Brodick north & south

McKay applauds the very best

While McBride’s potty mouth

Encurses scurrilous heckles

Whene’er a player flags

Cusses tosses at soft tackles

‘Play the game yer scallywags!’

& all the caileags roundabout

With wives & bairns & kinsfolk

Surround each cause with cheer & shout

Those roars all sports convoke

& Sarah Fullarton was there

Her daddy’d push’d the cycle

With shock of flaming scarlet hair

The darling of Kilmichael;

She wasn’t one for dolls & toys

Defining role & gender

Prefer’d instead to wrestle boys

Punch all who’d try defend her

The teams are set, the whistle blows,

The Lecamlet’s attack,

Like gallant tides the ebbs & flows

Of glorious Camanachd

The ball struck by the caman’s curl

As lads, shoulder-to-shoulder,

Do battle honour, heave & hurl,

& still the day swirls colder

The sky death-grey, the air snapp’d crisp

For heatbrief clapp’d the crowd

With each deep breath Will-o-the-Wisp

Did dance into a cloud

When from a slide of Arctic ice

The snow glides down in flurries

Soon slippy surface white as rice

Adds to the sweetheart’s worries

The keep display’d the shouts of men

The game sway’d to & fro

& up around Glen Rosa glen

The combatants would echo

‘Mecho-an-Laird’ the partisan

Cried, & ‘Mecho-Dol Homish’

Whene’er athletic artisan

A pauky move did finish

Somebody somewhere kept the score

But not a jot it matter’d

Tho’ on the pitch it felt like war

Each time the shins were shatter’d

But afterwards the teeming inn

All niggles would appease

By whiskey bottle & wineskin

A village at its ease

Where little John McAllister

Wee Wullie McIntyre

Pete Currie & the Minister

Were sitting by the fire

‘You’ll be as strong as them one day,‘

The Minister said smiling,

Not knowing an Appian way

Was wooden poles stockpiling

Awaiting them & countless more,

The zeitgeist lads alighting,

When first class empires go to war

Tis these who’ll do the fighting!

Lord Byron on Poets & Poetry

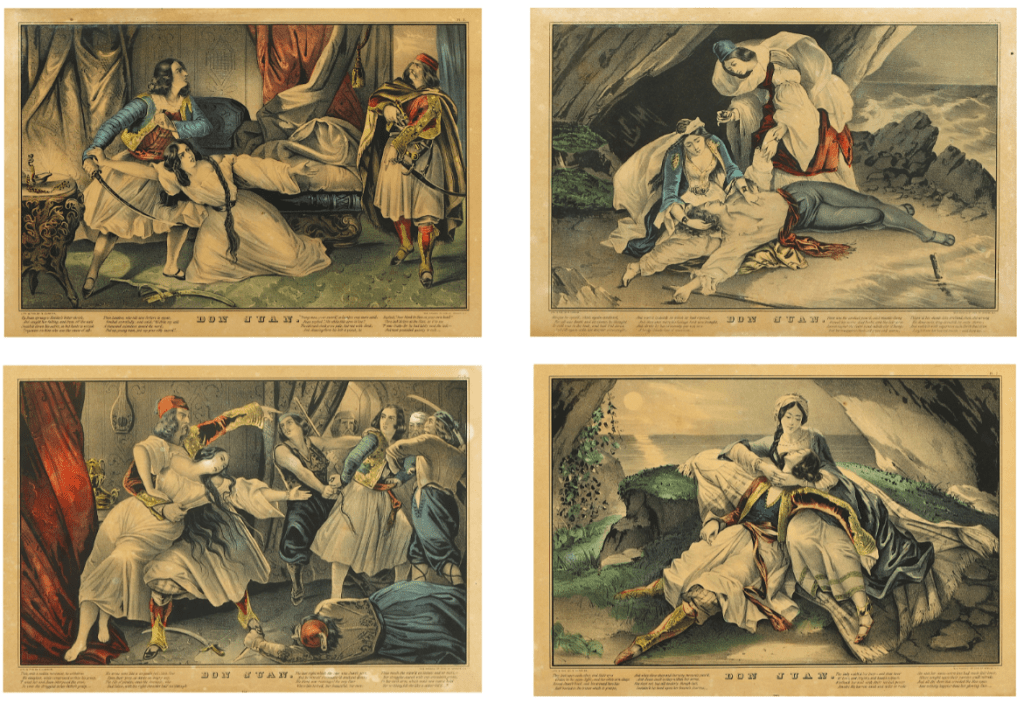

Embedded in canto III of Don Juan – stanzas 78-100 – is what can be consider’d Lord Byron’s ‘Apologie to poetry.’ It is a glorious mix of acute insight & criticism that reads amongst the best of his works. In the middle of the stanzas we can also find one of his most beautful ballads – named ‘The Isles of Greece’ – which invokes & laments the freedom of Greece. The extract begins with Juan & his recently acquired ladyfriend, Haidee, are lavishly entertaining in her father’s house, who they think as actually dead. Among the entertainers there is a famous poet which becomes the mouthpiece for Byron’s panaramic exposition of poetry.

And now they were diverted by their suite,

Dwarfs, dancing girls, black eunuchs, and a poet,

Which made their new establishment complete;

The last was of great fame, and liked to show it:

His verses rarely wanted their due feet;

And for his theme—he seldom sung below it,

He being paid to satirize or flatter,

As the psalm says, ‘inditing a good matter.’

He praised the present, and abused the past,

Reversing the good custom of old days,

An Eastern anti-jacobin at last

He turn’d, preferring pudding to no praise—

For some few years his lot had been o’ercast

By his seeming independent in his lays,

But now he sung the Sultan and the Pacha

With truth like Southey, and with verse like Crashaw.

He was a man who had seen many changes,

And always changed as true as any needle;

His polar star being one which rather ranges,

And not the fix’d—he knew the way to wheedle:

So vile he ‘scaped the doom which oft avenges;

And being fluent (save indeed when fee’d ill),

He lied with such a fervour of intention—

There was no doubt he earn’d his laureate pension.

But he had genius,—when a turncoat has it,

The ‘Vates irritabilis’ takes care

That without notice few full moons shall pass it;

Even good men like to make the public stare:—

But to my subject—let me see—what was it?-

O!—the third canto—and the pretty pair—

Their loves, and feasts, and house, and dress, and mode

Of living in their insular abode.

Their poet, a sad trimmer, but no less

In company a very pleasant fellow,

Had been the favourite of full many a mess

Of men, and made them speeches when half mellow;

And though his meaning they could rarely guess,

Yet still they deign’d to hiccup or to bellow

The glorious meed of popular applause,

Of which the first ne’er knows the second cause.

But now being lifted into high society,

And having pick’d up several odds and ends

Of free thoughts in his travels for variety,

He deem’d, being in a lone isle, among friends,

That, without any danger of a riot, he

Might for long lying make himself amends;

And, singing as he sung in his warm youth,

Agree to a short armistice with truth.

He had travell’d ‘mongst the Arabs, Turks, and Franks,

And knew the self-loves of the different nations;

And having lived with people of all ranks,

Had something ready upon most occasions—

Which got him a few presents and some thanks.

He varied with some skill his adulations;

To ‘do at Rome as Romans do,’ a piece

Of conduct was which he observed in Greece.

Thus, usually, when he was ask’d to sing,

He gave the different nations something national;

‘T was all the same to him—’God save the king,’

Or ‘Ca ira,’ according to the fashion all:

His muse made increment of any thing,

From the high lyric down to the low rational:

If Pindar sang horse-races, what should hinder

Himself from being as pliable as Pindar?

In France, for instance, he would write a chanson;

In England a six canto quarto tale;

In Spain, he’d make a ballad or romance on

The last war—much the same in Portugal;

In Germany, the Pegasus he ‘d prance on

Would be old Goethe’s (see what says De Stael);

In Italy he ‘d ape the ‘Trecentisti;’

In Greece, he sing some sort of hymn like this t’ ye:

THE ISLES OF GREECE.

The isles of Greece, the Isles of Greece!

Where burning Sappho loved and sung,

Where grew the arts of war and peace,

Where Delos rose, and Phoebus sprung!

Eternal summer gilds them yet,

But all, except their sun, is set.

The Scian and the Teian muse,

The hero’s harp, the lover’s lute,

Have found the fame your shores refuse;

Their place of birth alone is mute

To sounds which echo further west

Than your sires’ ‘Islands of the Blest.’

The mountains look on Marathon—

And Marathon looks on the sea;

And musing there an hour alone,

I dream’d that Greece might still be free;

For standing on the Persians’ grave,

I could not deem myself a slave.

A king sate on the rocky brow

Which looks o’er sea-born Salamis;

And ships, by thousands, lay below,

And men in nations;—all were his!

He counted them at break of day—

And when the sun set where were they?

And where are they? and where art thou,

My country? On thy voiceless shore

The heroic lay is tuneless now—

The heroic bosom beats no more!

And must thy lyre, so long divine,

Degenerate into hands like mine?

‘T is something, in the dearth of fame,

Though link’d among a fetter’d race,

To feel at least a patriot’s shame,

Even as I sing, suffuse my face;

For what is left the poet here?

For Greeks a blush—for Greece a tear.

Must we but weep o’er days more blest?

Must we but blush?—Our fathers bled.

Earth! render back from out thy breast

A remnant of our Spartan dead!

Of the three hundred grant but three,

To make a new Thermopylae!

What, silent still? and silent all?

Ah! no;—the voices of the dead

Sound like a distant torrent’s fall,

And answer, ‘Let one living head,

But one arise,—we come, we come!’

‘T is but the living who are dumb.

In vain—in vain: strike other chords;

Fill high the cup with Samian wine!

Leave battles to the Turkish hordes,

And shed the blood of Scio’s vine!

Hark! rising to the ignoble call—

How answers each bold Bacchanal!

You have the Pyrrhic dance as yet,

Where is the Pyrrhic phalanx gone?

Of two such lessons, why forget

The nobler and the manlier one?

You have the letters Cadmus gave—

Think ye he meant them for a slave?

Fill high the bowl with Samian wine!

We will not think of themes like these!

It made Anacreon’s song divine:

He served—but served Polycrates—

A tyrant; but our masters then

Were still, at least, our countrymen.

The tyrant of the Chersonese

Was freedom’s best and bravest friend;

That tyrant was Miltiades!

O! that the present hour would lend

Another despot of the kind!

Such chains as his were sure to bind.

Fill high the bowl with Samian wine!

On Suli’s rock, and Parga’s shore,

Exists the remnant of a line

Such as the Doric mothers bore;

And there, perhaps, some seed is sown,

The Heracleidan blood might own.

Trust not for freedom to the Franks—

They have a king who buys and sells;

In native swords, and native ranks,

The only hope of courage dwells;

But Turkish force, and Latin fraud,

Would break your shield, however broad.

Fill high the bowl with Samian wine!

Our virgins dance beneath the shade—

I see their glorious black eyes shine;

But gazing on each glowing maid,

My own the burning tear-drop laves,

To think such breasts must suckle slaves

Place me on Sunium’s marbled steep,

Where nothing, save the waves and I,

May hear our mutual murmurs sweep;

There, swan-like, let me sing and die:

A land of slaves shall ne’er be mine—

Dash down yon cup of Samian wine!

Thus sung, or would, or could, or should have sung,

The modern Greek, in tolerable verse;

If not like Orpheus quite, when Greece was young,

Yet in these times he might have done much worse:

His strain display’d some feeling—right or wrong;

And feeling, in a poet, is the source

Of others’ feeling; but they are such liars,

And take all colours—like the hands of dyers.

But words are things, and a small drop of ink,

Falling like dew, upon a thought, produces

That which makes thousands, perhaps millions, think;

‘T is strange, the shortest letter which man uses

Instead of speech, may form a lasting link

Of ages; to what straits old Time reduces

Frail man, when paper—even a rag like this,

Survives himself, his tomb, and all that ‘s his.

And when his bones are dust, his grave a blank,

His station, generation, even his nation,

Become a thing, or nothing, save to rank

In chronological commemoration,

Some dull MS. oblivion long has sank,

Or graven stone found in a barrack’s station

In digging the foundation of a closet,

May turn his name up, as a rare deposit.

And glory long has made the sages smile;

‘T is something, nothing, words, illusion, wind—

Depending more upon the historian’s style

Than on the name a person leaves behind:

Troy owes to Homer what whist owes to Hoyle:

The present century was growing blind

To the great Marlborough’s skill in giving knocks,

Until his late life by Archdeacon Coxe.

Milton ‘s the prince of poets—so we say;

A little heavy, but no less divine:

An independent being in his day—

Learn’d, pious, temperate in love and wine;

But, his life falling into Johnson’s way,

We ‘re told this great high priest of all the Nine

Was whipt at college—a harsh sire—odd spouse,

For the first Mrs. Milton left his house.

All these are, certes, entertaining facts,

Like Shakspeare’s stealing deer, Lord Bacon’s bribes;

Like Titus’ youth, and Caesar’s earliest acts;

Like Burns (whom Doctor Currie well describes);

Like Cromwell’s pranks;—but although truth exacts

These amiable descriptions from the scribes,

As most essential to their hero’s story,

They do not much contribute to his glory.

All are not moralists, like Southey, when

He prated to the world of ‘Pantisocracy;’

Or Wordsworth unexcised, unhired, who then

Season’d his pedlar poems with democracy;

Or Coleridge, long before his flighty pen

Let to the Morning Post its aristocracy;

When he and Southey, following the same path,

Espoused two partners (milliners of Bath).

Such names at present cut a convict figure,

The very Botany Bay in moral geography;

Their loyal treason, renegado rigour,

Are good manure for their more bare biography.

Wordsworth’s last quarto, by the way, is bigger

Than any since the birthday of typography;

A drowsy frowzy poem, call’d the ‘Excursion.’

Writ in a manner which is my aversion.

He there builds up a formidable dyke

Between his own and others’ intellect;

But Wordsworth’s poem, and his followers, like

Joanna Southcote’s Shiloh, and her sect,

Are things which in this century don’t strike

The public mind,—so few are the elect;

And the new births of both their stale virginities

Have proved but dropsies, taken for divinities.

But let me to my story: I must own,

If I have any fault, it is digression—

Leaving my people to proceed alone,

While I soliloquize beyond expression;

But these are my addresses from the throne,

Which put off business to the ensuing session:

Forgetting each omission is a loss to

The world, not quite so great as Ariosto.

I know that what our neighbours call ‘longueurs’

(We ‘ve not so good a word, but have the thing

In that complete perfection which ensures

An epic from Bob Southey every spring),

Form not the true temptation which allures

The reader; but ‘t would not be hard to bring

Some fine examples of the epopee,

To prove its grand ingredient is ennui.

We learn from Horace, ‘Homer sometimes sleeps;’

We feel without him, Wordsworth sometimes wakes,—

To show with what complacency he creeps,

With his dear ‘Waggoners,’ around his lakes.

He wishes for ‘a boat’ to sail the deeps—

Of ocean?—No, of air; and then he makes

Another outcry for ‘a little boat,’

And drivels seas to set it well afloat.

If he must fain sweep o’er the ethereal plain,

And Pegasus runs restive in his ‘Waggon,’

Could he not beg the loan of Charles’s Wain?

Or pray Medea for a single dragon?

Or if, too classic for his vulgar brain,

He fear’d his neck to venture such a nag on,

And he must needs mount nearer to the moon,

Could not the blockhead ask for a balloon?

‘Pedlars,’ and ‘Boats,’ and ‘Waggons!’ Oh! ye shades

Of Pope and Dryden, are we come to this?

That trash of such sort not alone evades

Contempt, but from the bathos’ vast abyss

Floats scumlike uppermost, and these Jack Cades

Of sense and song above your graves may hiss—

The ‘little boatman’ and his ‘Peter Bell’

Can sneer at him who drew ‘Achitophel’!

The Kilmarnock Burns And Book History

Patrick Scott is Research Fellow for Scottish Collections and Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the Department of English Language and Literature at the University of South Carolina. His work on the Kilmarnock Edition is a must read for all fans of Rabbie Burns.

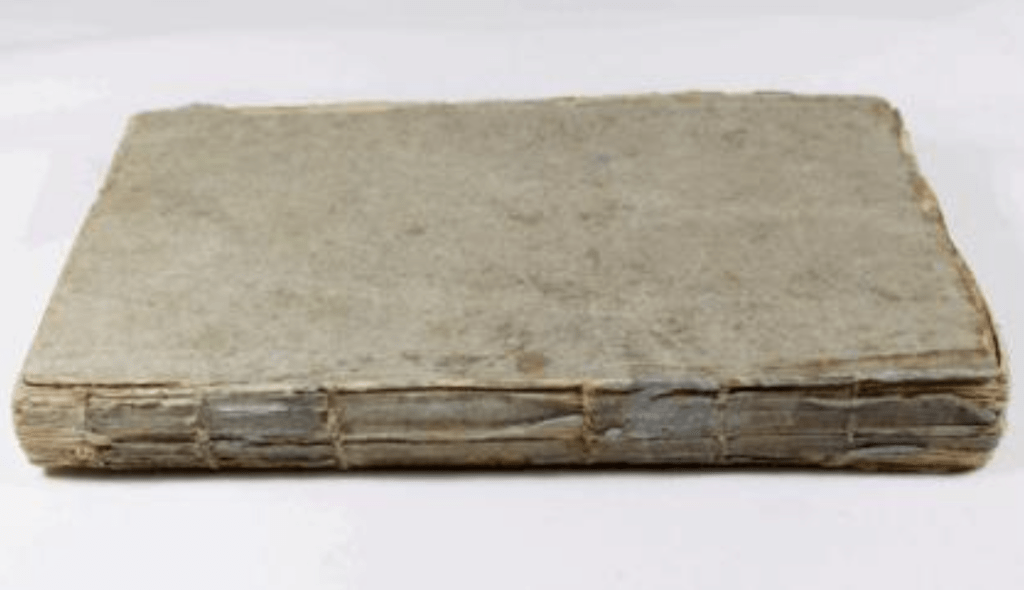

Allan Young and I have just published the first-ever attempt to track down all surviving copies of Burns’s first book, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (Kilmarnock: Wilson, 1786), the Kilmarnock Burns (1). Mr Young started working on this project fifteen years ago, and I have been collaborating with him for the past two years. We located just eighty-four surviving copies, which makes Burns’s book three times rarer than the Shakespeare First Folio.

At one level, this project might seem merely antiquarian. As early as 1903, the purchase of a Kilmarnock by the Burns Monument trustees was fiercely denounced in an Aberdeen newspaper:

Really, I think it is absurd for the Burns Trustees to throw away so much money […] Private individuals may spend their thousands on first editions if they choose: but could the memory of Burns not be honoured in a more practical way than by giving £1,000 for a book which is to go in a glass case and be looked at by tourists? (2)

Yet one of the big recent shifts in literary studies has been the growing interest in ‘book history’, and in the material forms in which we encounter literary texts. Mr. Young and I were not just listing the eighty-four copies, but trying to describe them and track their stories. After 230 years, the ravages of time and the pride of former owners have left marks on each surviving copy. Many copies carry ownership inscriptions, annotations, or bookplates. Some include manuscript poems, a few in Burns’s hand. Successive bindings and re-bindings mean that the copies vary quite a bit in size. Some have tears or missing leaves, and even after repair and replacement, most restoration leaves detectable traces. The accumulative of such changes makes every copy distinctive, and through reading these differences one can reconstruct changing attitudes to this book, and to Burns himself.

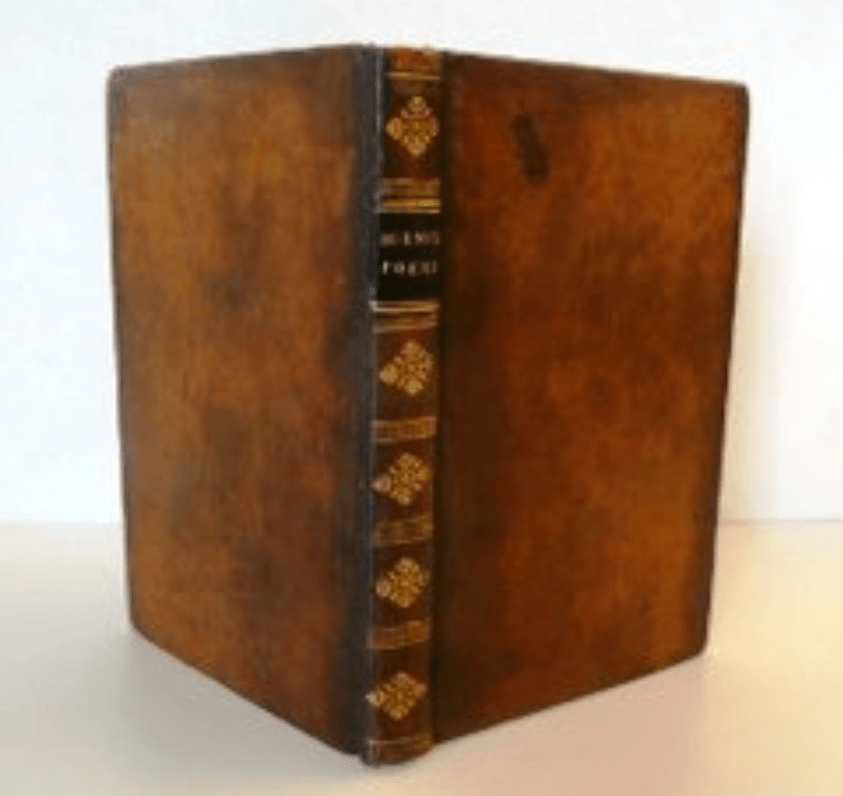

Like much about Burns, the story is very easy to oversimplify. To its first readers, in July and August 1786, Burns’s book made its appearance in plain blue-gray paper wrappers, with the page edges untrimmed, and it was available chiefly through local distribution to subscribers in Ayrshire itself. The wrappers were fragile, and the paper spine cracked away easily, so few copies survive in this original form, but one is at Alloway, in the Birthplace Museum (the same copy that drew that protest in 1903), and it can be viewed on the RBBM website. (3)

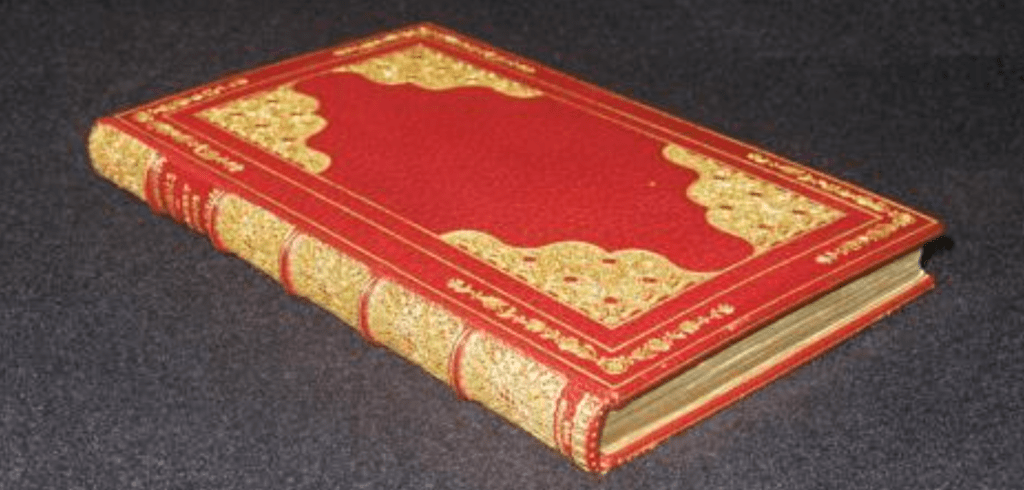

But just as Henry Mackenzie’s ‘Heav’n-taught ploughman’ would morph into the late Victorian National Bard, so the Kilmarnock’s original fragile wrappers would in time typically be replaced by fine bindings in gold-tooled full morocco, from such noted London binders as Bedford or Rivière. The majority of copies now surviving are in a binding from this period, though not all quite as spectacular as the one illustrated below, which Ross Roy used to say was more appropriate for the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam than for a Kilmarnock. (4)

Such bindings were not only a statement about the importance of Burns, but also of the owner’s wealth and status, and the best examples are collectible in their own right: indeed, most copies in fine bindings were housed in their own protective morocco slip cases or boxes that to the casual eye look equally impressive. By 1900, Burns was not only a prestige author, but an international one. Both buyers and prices had changed: instead of an Ayrshire farmer the typical early twentieth-century Kilmarnock purchaser might be a Scottish peer or an American railroad baron. Burns’s original subscribers had paid just 3 shillings (15p), but in 1929 a copy sold at auction for £2,550 (£140,000 at current value). In 2017, while there are still six copies in Ayrshire, and twenty-five in Scotland, there are at least forty-eight in the United States.

The contrast seems obvious enough. A Kilmarnock as originally issued was all of a piece with hodden gray, hamely fare, and a’ that. The Kilmarnock as later collected was a precious icon of world literature. Relatively few of the later collectors aimed to build a comprehensive collection of Burns editions. Most of them were adding a Kilmarnock alongside other Great Books. Indeed, part of its prestige in the market was its inclusion in One Hundred Books Famous in English Literature, a collector-list published in 1902 by the Grolier Club of New York.

Both sides of this contrast need more nuance. The original page format and paper show the Kilmarnock was always intended to look superior to John Wilson’s previous books. The distinctive title-page decorations, also used throughout the book, seem to have been specially purchased to reflect this ambition. The paper covers were intended to be temporary, and most purchasers had their copy put in a more serviceable binding; Burns himself told his friend John Richmond ‘you must bind it neatly’. (5)

These early bindings, rather than the copies in wrappers, show best how Burns was read by his Ayrshire contemporaries. Distribution also qualifies too populist a narrative. As Richard Sher has pointed out, the immediate economic success of the volume came more from the backing of a few major supporters than from individual subscribers; over two thirds of the 612 copies were bought by just seven names. (6) In November 1786, when a letter to the Edinburgh Evening Courant complained that ‘not one’ of Ayrshire’s ‘Peers, Nabobs, and wealthy Commoners’ had ‘stepped forth as a patron’ to Burns, Gavin Hamilton fired back that, of the original print run, ‘the greatest part […] were subscribed for, or bought up by, the gentlemen of Airshire’. (7)

On the other side, even in the 1890s and early 1900s, many individual Kilmarnock owners on both sides of the Atlantic have not been people of great wealth. Duncan M’Naught, longtime editor of the Burns Chronicle, was parish schoolmaster of Kilmaurs, but owned two Kilmarnocks. One of the most famous wrappered Kilmarnocks was owned in the 1890s by A. C. Lamb, proprietor of a temperance hotel in Dundee. By 1900, too, many copies had become tatty, and the elaborate bindings played an important role in their survival. Unlike the Shakespeare First Folio, the Kilmarnock Burns is a thin volume that, in an undistinguished early binding or in bad condition, could well be overlooked when an owner dies or a house is cleared. Part C of our book contains several anecdotes of this kind. It was not till the collector generation that the special importance of the surviving wrappered copies was recognized, and the competition between collectors who couldn’t get one put a special premium on other copies with early inscriptions or manuscript material. Once a Burns manuscript had been bound up with a Kilmarnock in red morocco gilt, its survival was ensured. It was many years later before university libraries and other public institutions took over this role to any significant extent.

In his own times, Burns’s poetry was disseminated in many different ways, not just in books, from manuscript and oral transmission to newspapers, chapbooks and broadsides. Burns himself wrote a satiric squib about fine bindings and insect damage in an aristocratic library:

Through and through th’inspired leaves,

Ye maggots, make your windings,

But, oh! Respect his lordship’s taste,

And spare his golden bindings. (8)

Two centuries later, the importance of Burns’s own poems means that all Kilmarnocks, whatever their binding, can be of great research interest as well as of monetary value. Even a copy that is damaged or imperfect tells a story. It is often through the material form in which Burns’s first book has survived, in the ambitious ‘improvements’ made by earlier owners and in the traces of neglect or mishandling, that we can now reconstruct the varied ways in which Burns has been valued.

End Notes

1 – Allan Young and Patrick Scott, The Kilmarnock Burns: A Census (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Libraries, 2017). The discussion here draws from my introductory essay, ‘Describing the Kilmarnock’, pp. xxi-xxxvi, which gives fuller references.

2 – Aberdeen Journal, July 29, 1903, p. 10.

3 – Robert Burns Birthplace Museum object 3:3135

G4 – . Ross Roy, in Burns Chronicle Homecoming 2009, ed. Peter J. Westwood (Dumfries: Burns Federation, 2010), p. 415.

5 – Letters of Robert Burns, ed. G. Ross Roy (Oxford: Clarendon, 1985), I: 50.