Uncategorized

Zaffar Kunial with Jackie Kay: Between the Dee and the Don

Kaye began by reading three of her own poems. ‘Between the Dee and the Don’, from her celebrated collection ‘Fiere’, set the tone for the discussion. ‘The middle ground is the best place to be’, as so often expounded by the wise, is an Igbo saying, the tribe of her Nigerian biological father. The poem is a celebration of being bi-racial, bi-cultural, and not having to choose one over the other. This self-defined stability is a strong statement; vital after years of confusing experiences tugging and tossing you between different strands of your heritage. She recounts a funny story of a man on a train seeing her Igbo genes shining out of her face. His enthusiastic exclamations at her ‘good Igbo nose, and good Igbo teeth!’ fill her with pride and make the audience laugh. We feel the excitement and pleasure of parts of her being not just identified but celebrated, fuelling long-held and poignant dreams of fully belonging as she painstakingly create her own connections with elusive ancestry. Jackie longs for the connection with Nigeria, as ‘I dance the dance I never knew’, and just as she begins to embrace this identity as an African woman, comes the shock at the reality of being boxed into a category that again, doesn’t quite fit the complexity of self, as she is called Oyinbo (white person) by the market women!

Jess Smith: The Turbulent Tale of Scotland’s Gypsies

Her soft voice drew you in to ‘relax and listen around the fire’, just as she grew up listening to stories. She began with her own funny childhood memories of her father bringing home a 1948 Bedford bus for her mother to live in, continuing to quell her mother’s protestations, “you can make it like Balmoral I’m not biding in that!”, with more and more luxury customisations. Eventually she gave in, and continued the travelling tradition with the ‘mansion’ her husband had brought her. These memories are obviously well known to her avid fans in the audience in the form of her first autobiographical book, Jessie’s Journey. Even though the success of that first book shocked her by running at no.1 in Scotland, ‘above Lauren Bacall’, she felt compelled to tell the world the relatively unknown history of discrimination by non-gypsies and revelled in telling us the fascinating coincidences that led her to tell the story. Fate firmly tapping on her shoulder until it was done.

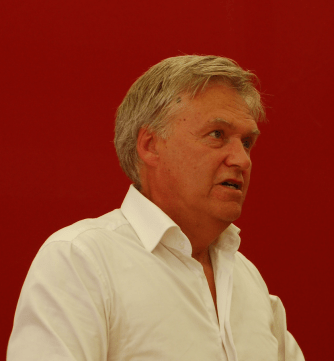

Iain Macwhirter

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Baillie Gifford Main Theatre

15th August 2016

In 1933, author Eric Linklater stood for Parliament in the Scottish constituency of East Fife. He stood as a candidate for the fairly new National Party of Scotland, and lost his deposit. Fast forward to 2015, and the SNP, successor to the National Party of Scotland, won fifty-six seats out of a total of fifty-nine Scottish constituencies, in the UK’s general election. In his book Tsunami: Scotland’s Democratic Revolution, Macwhirter proposes that this fact represents just that – a revolution.

Iain Macwhirter is one of Scotland’s most influential political commentators, he’s the go-to guy if you want to read informed opinion about Scottish current affairs and recent history. To me he occupies the position of ‘Bakunin’s bootmaker’ – someone to whom I would listen before making my up own mind, someone whose status as an expert is an indispensible resource, but not an argument-closer.

There has certainly been a buzz in the air in Scotland since the close-run independence referendum, the 2015 election, and the UK-wide referendum on EU membership. If nothing else has truly changed, then the level of public engagement with and interest in the world of ‘politics’ has certainly increased. I put the word ‘politics’ in quotes here, because I well remember the caveats advanced at the 2015 Book Festival by Professor Erik Swyngedouw about that term’s appropriateness, when what is actually meant is the technocratic-managerial role of the State and its functionaries.

This event was the second I have attended so far this year in the Baillie Gifford Theatre. I reported that the last one suffered a little because of pace and acoustics. This one much less so. This was mainly because Iain Macwhirter has a great deal of information and opinion at his fingertips. He is never at a loss for words, and talks rapidly to get his points in. As a former BBC political correspondent, he has had a lot of practice in the broadcast media, and I would guess this is where that particular communication skill comes from. For the purposes of this Book Festival event, he was interviewed by eminent journalist Magnus Linklater, the son of the NPS’s unsuccessful candidate in 1933. Linklater was, in many ways, a perfect pick for the position, being professionally aware of all the issues that Macwhirter has covered in his new book, and was likely to cover in the allocated hour, as well as having that family connection. The auditorium was packed, I don’t think there was a single empty seat, which probably reflects that increase in ‘political’ engagement in Scotland (there I go again with the quotation marks).

The Q&A session was lively, some of the questions being very penetrating, again indicating the level of engagement. I would have liked to ask Macwhirter a detailed question where I could have repeated back to him, using his own words, some of the arguments he had presented in support of his hypothesis that there had been a ‘revolution’ in Scottish politics; however, I was obliged to ask a truncated question which could not get across more than a couple of the necessary points, and thus his answer was not convincing either. This I put down to the nature of Book Festival events, which have to fit this strict introduction/interview/Q&A format into a single hour, not to a lack of intelligence in either the questioner or the respondent! I now have the luxury of being able to put this right in this review, and I think it is a very relevant challenge.

To be fair, Macwhirter did admit, when Linklater first mentioned it, that the words ‘Tsunami’ and ‘Revolution’ in the title of the book were ‘publication hyperbole’ to a great extent. Nevertheless, he maintained, a revolution does not necessarily mean gunfire and barricades in the street. No, it doesn’t – it means a complete, rapid, and palpable change. The first flaw in Macwhirter’s hypothesis rests, I would say, in his strict focus on the most recent events, in the fact that he looked back – in his talk certainly – principally at what had happened over the past five years, and in particularly the SNP’s electoral success. In fact the party’s growth has been gradual, and in direct proportion to the decline of the Labour Party north of the border, to the cessation of the boom in council housebuilding since the 1960s, and the decline in unionised industry. The timescale involved was enough to build a thousand barricades, if anyone had felt so inclined.

Macwhirter made a point of mentioning that the SNP had, since the time of Tony Blair’s invention of ‘New Labour’ on Thatcherite principles, adopted and adapted many of the policies that the Labour Party had previously held. No revolution here, then – simply the re-labeling of existing ideas, the maintenance of the status quo under a different brand. He mentioned the referendum on independence; in that referendum the population of Scotland decided, albeit with a fairly tight margin, to remain part of the UK, again a vote for the status quo. He mentioned, of course, the stunning results in Scotland in the general election of 2015. However, he went on to describe Nicola Sturgeon’s cautious and pragmatic political philosophy of ‘utilitarian nationalism’, which regards independence not as an end in itself but as the best way of securing social justice, and the way in which it had recently drifted slightly away from the party’s relatively ‘Old Labour’ radicalism and back to a more centrist, managerial style. This swing back towards the status quo is something we see quite often in the policy of a party which wins power or a considerable and important influence within an existing power structure.

Then along comes the EU referendum, in which although the UK overall voted for leaving that organisation, Scotland voted for remaining – in effect once again for the status quo. Right now, with the probability that Theresa May will not even consider triggering Article 50 until 2019 at the earliest, and that a second referendum on Scottish independence is unlikely soon, the panic over Brexit seems to have faded a little.

I ask this: with all this status-quo breaking out everywhere, where the hell’s the revolution?

I noticed that when Macwhirter answered my truncated question, he felt it necessary to repeat the proviso about ‘revolution’ not meaning guns and barricades. Nevertheless his answer was full of “still so-and-so…” and “still such-and-such…” Iain, I have to tell you that ‘still’ is not a word you should associate with ‘revolution’! I wasn’t satisfied with his answer, and nor were the handful of people I spoke to afterwards. I can’t speak for the rest of the large audience, of course.

All the foregoing might lead you to think that I didn’t enjoy the session. Nothing could be further from the truth. Iain Macwhirter is a person with a wealth of facts and opinions at his fingertips. He has been observing the political scene, particularly in Scotland, for quite a while. The event overall was interesting and stimulating. As I look forward to the rest of the political figures booked to appear at this year’s International Book festival – the likes of Roy Hattersley and Gordon Brown – I wonder if those sessions are going to be half as engaging.

Even though I believe its hypothesis can’t be successfully supported, I would recommend Iain Macwhirter’s book as, if nothing else, a detailed explanation of what has been happening in Scottish statecraft, and the public’s engagement with it, during recent years. Had you been there on the day, you could have picked up a signed copy along with a bundle of some of his earlier books thrown in free! One of the perks of being there on the day at the Book Festival.

Reviewed by Paul Thompson

Goretti Kyomuhendo: Africa’s Independent Voices

–

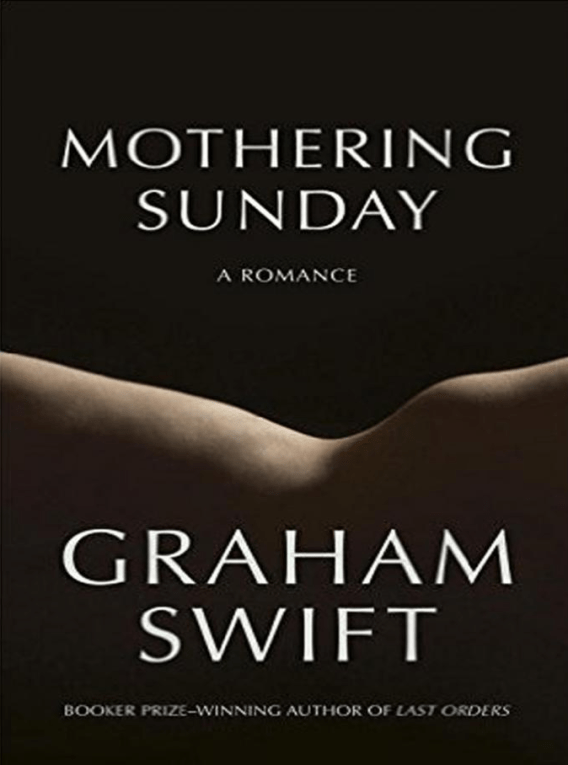

Graham Swift

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Baillie Gifford Main Theatre

13th August 2016

The Baillie Gifford Theatre is the largest event space in the Book Festival, so it is inevitable that it should be used for an author of the calibre of Booker-winner Graham Swift. Where else would you want to install him? This did result in some problems. Journalist Rosemary Goring, who chaired the event and interviewed Graham, appeared to have a comparatively soft voice that was not always enhanced by the amplification offered by her microphone. The author’s own normal delivery is slow and deliberate. If you add to that the rushing noise of a ventilation system (if that’s what it was), the result could be rather soporific for someone sitting at the back. Just one of those things!

On the other hand those conditions could just as easily make an audience concentrate its attention on what was being said. Once Graham was at the lectern, giving a reading from his new novel Mothering Sunday, we were all attention. He read from the beginning of the novel, which starts with the fairytale opening “Once upon a time” and describes the events of a single day, in 1924, in the life of a domestic servant; hers is the novel’s ‘voice’, as she looks back on events that happened several decades previously, since when she has become an author. There is a description of the ownership of a racehorse – how the head and body belong to one person, a leg each to others, and so on – and of the post-coital nakedness of the voice and the man with whom she is having an illicit affair. There is a nakedness and a deliberation in the words also, “… cock… balls… cunt…” and a poignancy in the knowledge that this is to be their last meeting before his marriage. The voice, Jane Fairchild – and what an ironic name that is for a motherless foundling on Mothering Sunday – finds herself at a pivotal moment in her life. How different it might have been if she had had a mother to go home to, rather than a lover to spend time with, and a borrowed copy of a story by Joseph Conrad to read.

Rosemary Goring suggested that the book was “saturated with sex, but nothing explicit.” Graham Swift disputed the term ‘saturated’, maintaining that a good author could (should?) “allow a few details to say the whole… You have to leave space for the reader’s imagination.” Mothering Sunday had been an idea that had simply occurred to him and was written very quickly, and when it was finished he set about editing it, even though it was short in its unedited state. Another thing that he disputes is the application of the term ‘novella’ to Mothering Sunday. To him it is a novel, with all the essential complexity of that form. “I never had any doubt about its dimensions,” he said, and attributed his confidence in the book, and in the process of writing and editing it, to his maturity as a writer.

Further discussion provided insights into that process, almost becoming a ‘how to’ lesson. Mothering Sunday isn’t the first published work by Graham Swift to be structured around the happenings of a single day. Nor is he only writer to structure a novel like that; as soon as I knew that Mothering Sunday dealt with a single day in the mid-1920s, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway sprung to my mind. However, Mothering Sunday is not a ‘modernist’ text, nor is it full to the brim with streams of consciousness. Similarly, as soon as I knew that there was no description of Jane Fairchild I thought of the second Mrs de Winter in du Maurier’s Rebecca. However, these are probably false associations, because the more I listened to Graham Swift, the more he seemed to be a writer who is very self-aware, aware of the processes I mentioned, and who does not consciously let other writers tap him on the shoulder as he writes.

The session is not about the book itself, and really this review ought not to dwell too much on it either. The session is about the author talking about the book. Judging how good one of these events is, therefore, is not always easy – it’s not the same as a poetry reading, a concert, a comedy turn, it’s not a performance per se. A session with an author at the Book Festival can be predictably formulaic: Introduction, reading, interview, Q&A, and the inevitable “I’m afraid that’s all we’ve got time for…” This one didn’t exactly sparkle, but it definitely held my interest. There is no formula for awarding stars for this kind of event, and after all, each one is a one-off and all must be seen in the context of Charlotte Square in August. All I can do is gauge it against the others I have seen in previous years, so what I will say is that despite the auditorium difficulties the event was what I have come to expect of the Book Festival when it hosts a serious author.

Reviewed by Paul Thompson

Loud Poets

Broadcast, Glasgow

9 June 2016

—-

Striking comic books are often stitched together using bright, vivid characters between multi-coloured pages which are filled with untamed slapstick from start to finish. These stories are crammed into fairly short magazines whereby one-liners and plots appear inside speech-bubbles materialising from character’s mouths, filling hearts with glee as, on a weekly or monthly basis, each personality’s little idiosyncrasies proceed to leave their own animated impression on us, the readers. And herein lies the successful formula which Edinburgh’s Loud Poets collective abide by.

Striking comic books are often stitched together using bright, vivid characters between multi-coloured pages which are filled with untamed slapstick from start to finish. These stories are crammed into fairly short magazines whereby one-liners and plots appear inside speech-bubbles materialising from character’s mouths, filling hearts with glee as, on a weekly or monthly basis, each personality’s little idiosyncrasies proceed to leave their own animated impression on us, the readers. And herein lies the successful formula which Edinburgh’s Loud Poets collective abide by.

Describing their shows as slam-style, make some noise, fist-thumping, pint-drinking, side-tickling, heart-wrenching poetry, attending a Loud Poets performance is perhaps not intended for sweet-tempered cardigan-clad librarians cycling home to pots of Earl Grey tea but the treasure lies within the coursing array of performers selected each month; some as brash and atypical as one may expect, others perspicacious, canny, and dare I say it, controlled. This month’s event, the final one during this cycle, was advertised as “Exile On Sauchiehall Street”, a play on the name of the 1972 album released by The Rolling Stones, bringing together some of the most exciting, mostly young, talents in the Scottish spoken word scene today:

Kevin McLean – Iona Lee – Jack Macmillan -Freddie Alexander -Catherine Wilson – Michelle Fisher – Katharine Macfarlane – Katie Ailes – Hugh Kelly (musician) – Loud Band – Open Mic poets

It is Loud Poets tradition now to begin proceedings with the Open Mic set, allowing newcomers to try out the audience and, subsequently, present themselves as the sacrificial poet. This month it was between Jade Mitchell, Ben Rodgers, and Fiona Stirling to fight it out. It was the solitary male who emerged victor, producing an endearing ramshackle performance, earning the right to be on the Loud Poets bill when the show returns in September 2016.

Adding to the mix were the Loud Poets backing band Ekobirds. This concept has been introduced with the aspiration of affixing extra value to each spoken word artists’ words, and whilst obviously demonstrating their own prowess, advertises the perks of musical accompaniment brings to poetry. Fresh from performing five days in Prague with the band, the Loud Poet mainstays Catherine Wilson, Kevin McLean, Freddie Alexander and Katie Ailes would all feature through different points of the evening, exhibiting exactly why this is rated as one of the highest regarded showcases of performance poetry in the country.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=veS_lnWFOtQ

As each poet introduces another, the night is kept fresh by a revolving door of one-poem performers leaping on and off the stage. Among the youngest performers of the evening, Jack MacMillan’s theatrical performances at regular poetry showcases such as Edinburgh’s Soapbox and Glasgow’s Aloud have turned him into a slam-winning shaman, delivering thunderous rituals in front of nothing less than the Scottish Slam Final audience. Jack’s fun, easy-going manner flourished during “I Wish I Had A Ladder”, slipping into the character Zed from the Police Academy franchise at times. His enthusiasm sometimes loses words, or vowels, such is the speed in which the performer delivers each line, but Jack’s zeal for not eating veal in his vegan poem later in the evening tapped into pertinent issue concerning agriculture, demonstrating there was more than just comedy and showmanship to the student’s talent.

Equally so, there is a depth to the words of Michelle Fisher which needs to be cherished. Selected for inclusion in BBC Radio 1Xtra’s Words First hunt for Scotland’s finest young poets, Michelle has developed into an exceedingly skilled poet over the last twelve months. Short, sharp rhyming structures were used to tackle body image, consumerism, and depression issues in her opening poem, only to be outdone by another effort concerning rape culture. Never shying away from thorny talking points, Michelle’s diagnosis of zoo visits being likened to “walking among predators” and “treated like cattle” actually convinced me that the piece concerned international terrorism, but the bullet-pointed delivery of the rules one must abide by (1. Do not touch the animals, 2. Do not feed the animals, etc) rammed home that this was a matter of unwelcome sexual harassment.

In Scottish Slam Champion, the Exile on Sauchiehall Street extravaganza scored a real coup as the sublime Iona Lee was welcomed on stage. The calm and ethereal delivery of Iona’s words danced beautifully with a haunting violin during new poem “Away With The Fairies”, casting a magic spell over the rambunctious audience. It is a treat to watch Iona deliver poems filled with turns of phrase similar in ilk to that of the UK Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy such as ‘nature’s half-heard whispers’. A study of a character haunted by his own ‘jaded heartbreaks and mistakes’, living a wretched existence ‘untroubled by the postman’ again demonstrated the remarkable clasp Iona has on using prepossessing language to describe preternatural stories, while the Ekobirds fitted provocative sounds beneath a flush vocal, none more so than on third poem “Bad Blood”.

Between the Loud Poets themselves, a sense of progression was apparent. Catherine Wilson’s philosophical questions about life were balanced by a degree of sharp-witted humour, while a self-study of anxiety issues was delivered with the reverence one would expect towards mental health. Catherine’s punch is pronounced with lines describing anxiousness akin to “a thousand bear traps in the mind / of doing a striptease at a funeral”. These are extraordinary lines which have no intention of tip-toeing round the matter at the core of her poems. Likewise, Katie Ailes continues to recite memories of her own in a manner that makes the listener think it was their childhoods, puberty, and adolescence. Katie’s delivery is one of such charming effect that the band behind her melts into the stories that the audience feasts on, digesting the morals which are conjured up about learning, music, creativity, and love.

On the Y chromosome of the Loud Poets collective, Kevin McLean introduced “The Game” in which the writer presents histories upon characters in and around Edinburgh city. This was a captivating, far more steadied performance from Kevin as he introduced Alice, Steven, and Bill at various stages through the evening – far less stage-driven but executed carefully, sincerely, and in a beguiling way which suggests new territory is being explored. The easy-going manner of Freddie Alexander, he of the much-heralded Inky Fingers spoken word night in Edinburgh, dips in and out of American folklore using occasional religious figurative language which remains with the listener – ‘A hunting rifle pointed at the exposed heart of God’ and ‘Listen to people – all their words are birdsong’ just two of the stunning lines which Freddie delivered. Did I mention that Freddie also did his dissertation on comic books? Well, he did! In fact, the only sour point, if I may call it such, was the continued finger-clicking adopted by persons who attend Loud Poets shows as a means of encouragement. Leave the thumbs for saluting the performers, folks – it’s naff and becoming something of a bugbear.

And so, one increasingly exciting poet to talk about. The evocative language used by Katharine Macfarlane to bring Scottish towns and countryside to life, using fleeting imagery and enchanting chronicles, have had listeners falling like roses thrown upon theatre stages (For reference, consider this sparse, 32 worded poem and the stone circle in Orkney which is at the seam of Katharine’s poem “Ring of Brodgar” http://stanzapoetry.org/blog/poetry-map-scotland-poem-no-190-ring-brodgar-orkney). Tonight, Katharine’s charms were reserved for matters of family concern – history, the future, knowledge, and identity all brought to the fore in a sweet-hearted ode to her four year old daughter. The parental love in Katharine’s poetry continued to flourish in her next poem, ‘counting the stars and what was left of the moon’, leaving a genuine empathy with anyone who recalls their parents being their best friends when they were young.

Between the two halves, the free sugary treat that comes with all comics appeared in the form of Hugh Kelly who delivered a stunning three-song set on guitar, including songs from his ‘Give Me All Your Love’ EP and a resounding cover of Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come”. Do check the musician out – he was a genuine delight and welcome addition to the evening’s proceedings.

The Loud Poets night does what it says on the tin. It encourages shouting from the audience, it insists on a camaraderie between performers and audience, and it is a delight to see live in person. For the performers, it is an opportunity to enhance their own skills – read without the safety net of a book in hand, play with a band behind you, and receive the genuine warmth and support of everyone in the room there as an audience member or as a peer. The collective continues to change since its inception in early 2014, and unlike the Bash Street Kids, there is a suspicion that each will keep taking poetry to higher levels, graduating into new territories. Check them out while we still have them.

Reviewer : Stephen Watt

Kate Tempest

Mitchell Library:

Aye Write Festival

14 April 2016

Think back to a decade ago. London always wanted social narrators who can spin a good yarn – Lily Allen, Kate Nash, Mike Skinner (Birmingham – Sssshhh), and perhaps the less said about N-Dubz contribution to popular music, the better. And then it all went a bit quiet. In terms of contemporary poet-musicians, the case remains very much in the ether as to who represents this category best.

Think back to a decade ago. London always wanted social narrators who can spin a good yarn – Lily Allen, Kate Nash, Mike Skinner (Birmingham – Sssshhh), and perhaps the less said about N-Dubz contribution to popular music, the better. And then it all went a bit quiet. In terms of contemporary poet-musicians, the case remains very much in the ether as to who represents this category best.

In the fourth centenary year of William Shakespeare’s death, one name has been grabbing a fair share of the public’s imagination and it is perhaps fitting that the final play which Shakespeare wrote was titled ‘The Tempest’. 31-year old Kate Tempest may be a new name in terms of tabloid recognition but the South-London rapper and poet has written plays, collections of poetry, playwrights, and was nominated for a Mercury Award in 2014 for her debut solo album ‘Everybody Down’. Perhaps it wasn’t so unexpected that tonight’s heroine received the prestigious title of being named as a Next Generation poet by the Poetry Book Society. It’s difficult to peg Tempest down to a solitary label and herein lies the beauty about her achievements thus far – one fantastic melting pot of artistry and ingenuity. Tonight’s agenda at Glasgow’s Mitchell Library was for the publication of her debut novel ‘The Bricks that Built the Houses’, published by Bloomsbury Publishing.

In front of a largely young and female audience, Tempest was introduced by another of the shining lights on the UK spoken word scene, Hollie McNish. Friends off the stage, it was an inspired choice of host as the two poets bartered comfortably between themselves, at times almost neglecting to remember that a couple hundred pairs of ears were tuned into their mic’d up conversation. Opening with the tongue planted firmly in her cheek, McNish questioned her colleague what the meaning of life was. This was answered by Tempest’s introduction to characters in her novel, and what their purpose was.

In front of a largely young and female audience, Tempest was introduced by another of the shining lights on the UK spoken word scene, Hollie McNish. Friends off the stage, it was an inspired choice of host as the two poets bartered comfortably between themselves, at times almost neglecting to remember that a couple hundred pairs of ears were tuned into their mic’d up conversation. Opening with the tongue planted firmly in her cheek, McNish questioned her colleague what the meaning of life was. This was answered by Tempest’s introduction to characters in her novel, and what their purpose was.

The new book regards a young trio who emerged from the Everybody Down record, Becky, Harry and Leon, who depart the city in possession of a suitcase full of stolen money. It is an exploration of contemporary urban life, which is kernel to Tempest’s writing, evaluating the communities we live in and the ethics by which we live. It is clearly a high priority on the poet’s plan for life as she reflected on the primary functions of communities, the support which is sorely lacking, and the need to break down barriers – using her characters need to delve into their past, their roots, and that sense of knowing one another’s families. It was a heartfelt introduction and one which, accidentally, made you fall a little in love with her – and her ideology.

Reading an excerpt from the book, Tempest opted to quote William Blake at the start – her favourite poet – before setting the scene of the society her characters were living in. Describing “the pain of watching someone turn into a shadow”, hand dancing along with each word, Tempest’s enthusiasm and energy was infectious. It was an important observation by Hollie McNish about reading the entire book out loud, ‘mimicking Kate’s voice to the point of beginning to sound like a dickhead’, that spurred the author on to divulge her belief that the reader was as important as the writer to make the text come alive; without which, the book will either gather dust or be read passively, without the feeling which was intended to strike into you. It became apparent why Public Enemy’s Chuck D is simply quoted as saying “Wow” on Tempest’s website – this was both enlightening and educational stuff.

On a lighter note, both poets discussed their shared editor, Scots poet Don Paterson, and the need to remove ego when edits are being enforced (“Pfft” and “Hmph” were both disclosed as examples of Paterson’s margin-notes). Other insecurities were touched upon in a friendly manner, including the shyness of discussing sex in the new novel, recovering from a marriage which never worked to plan, and the anxiety which haunts every writer’s mind – ‘waiting to be found out as a fraud’.

During the Q+A, members of the audience grabbed the opportunity to ask about writing processes, juggling various projects, influences and aspirations. Tempest used this opening to express her fascination with humanity, and dogma of ‘more empathy, less greed’ towards our fellow man and woman. This would have sounded remarkably corny had it not been expressed in such a sincere and tender manner, with the need for connecting to continue from poetry into her life.

On a final note discussing the writing process, our feature for the night entreated that “the finished product will never be as good as the idea in the head – deal with the agony”. It was, as the whole night had been, a highly amusing piece of advice which seemed entirely accurate. Something tells me that if this truly is the case, then some of the ideas inside Kate Tempest’s head must be truly formidable. Shakespeare was right all along; a storm is brewing.

Reviewer : Stephen Watt

A Very Short Introduction to Sound

A quiet and studious audience packed their way into the old-fashioned circular Anatomy Lecture Theatre in Summerhall, and it was interesting that for a lecture about sound, neither the acoustics not the microphone were optimized for easy listening. Mike Goldsmith was a fascinating lecturer, with books’ worth of knowledge tumbling forth in a steady stream for almost an hour. He is a freelance acoustician and science writer and the former Head of Acoustics at the National Physical Laboratory. One of his many books for adults and children is Discord: the Story of Noise and a slimmer book called, as the lecture, ‘A Very Short Introduction to Sound’.

A quiet and studious audience packed their way into the old-fashioned circular Anatomy Lecture Theatre in Summerhall, and it was interesting that for a lecture about sound, neither the acoustics not the microphone were optimized for easy listening. Mike Goldsmith was a fascinating lecturer, with books’ worth of knowledge tumbling forth in a steady stream for almost an hour. He is a freelance acoustician and science writer and the former Head of Acoustics at the National Physical Laboratory. One of his many books for adults and children is Discord: the Story of Noise and a slimmer book called, as the lecture, ‘A Very Short Introduction to Sound’.

He began with the basics, for us mere mortals, and sped off from there. He talked about the inherent difficulties with the objective and subjective dichotomy of the discussion of sound, but decided to define sound simply as an object oscillating; unless it’s an explosion of some kind or due to variations in heat. He discussed how important sound is, due to the fact that it can go through lots of different media, like water, air etc. He went on to explain the origin of sound, and that the first sound occurred very early on after the Big Bang. Sound is so important to us on a career level as such a wide variety of professions deal with sound, not just the obvious ones like musicians, but also including vehicle designers, sound artists, politicians, and generally that sound is so precious to us in our experience of daily life as humans.

He covered the dangers of sound, and the thresholds of sound that are comfortable and safe for the human ear, up to about 120 decibels, but also allowing for variation, as showed that some people are just more sensitive to the effects of sound. 90 decibels is just starting to become dangerous for our hearing. He discussed musician’s hearing being damaged by playing regularly in orchestras due to the noise level. The frequencies that we can hear change as we age, due to either the ageing process and general exposure to noise over a lifetime. There were chuckles in the audience as he talked about the rather cruel ‘mosquito device’ that vibrates at 16-17kHz and is supposed to be used for repelling teenagers, as by the time we reach adulthood we can no longer hear at those frequencies. One lady confided in me that she needed one for her challenging 26yr old son with ADHD who was refusing to leave home! Most people can hear up to 20kHz but there’s a small minority of people who can hear up to 30kHz. I’m always interested in learning about exceptions and why they happen, and made a mental note to find out more about their genetics and/or environment. He talked about the dangers of the frequency and level of noise in modern cities, and the effect it has on us as humans, and singled out that the type of frequency used in audio addresses in places like airports subways etc. have such a new, strong frequency that they may be doing damage to our hearing.

One of most fascinating parts of the lecture was when he showed a diagram of the density of cosmic sounds soon after the Universe was formed, and explained the patches you could see clearly were density variations due to ionised plasma falling into an area of local matter – like mini black holes. An in and out effect created, and basically a sound wave. He explained the low and long pitch of the sound of the universe expanding, and showed the density imbalances leading to the formation of planets. I wished he could have played a clip of the sound in the lecture, but instead I listened to the sound on the internet when I got home and it had a bizarre, grounding but also unsettling effect on my body.

He talked about sound in the ocean and its importance to sea creatures for quite a significant part of the talk. How sounds in the ocean are so much more important that light. Scientists measuring temperature change using sound-measuring devices. The ‘sound traps’ in the ocean that span large distances and both animals and humans send sound through them. Of course the whales beat us humans to this a long time ago; and use it for their communication over vast distances. Scientists think perhaps there was a time that the oceans were such that even Antarctic and Arctic whales could hear and communicate with each other!! The speed of travel of the sounds depends on the saltiness of the sea. I thought it was fascinating that under the water, sound frequencies split up, and touched on the fact that different sound frequencies in speech relay both the informational and the emotional components of speech, and I wondered if the different tonal aspects of various languages and dialects directly affect not just the population’s emotional expressions but emotional states .

He continued on to the basics of music, of course, and the fact that the foundations of music are in based firmly on physics. He touched on the makeup of a piano keyboard and the relationship between the C notes on a piano key board; the fact that if you double the frequency you get the next C along. Relationships of notes to each other depending on wavelengths. It made me think about different music systems in different cultures and how that affects people psychologically and physically. Also the fact that under colonial regimes, banning of ‘native’ instruments are often amongst the first laws to suppress a colonised people. He discussed the social and emotional effects of music, which are universal amongst all peoples, to a point. Which sounds create feelings of agitation and aggression, and which sounds are soothing to the human body/mind. The repetitive sound of trains are always more popular and experienced as less intrusive than aircraft noise. Aircraft are so much more disturbing to humans that house price goes down but it’s the opposite for trains. Prices can go up 10 per cent more for being near a train station! Helicopters are considered even more annoying, but studies have found that the experience is quite subjective, depending on what he helipcopter is being used for, people experienced it as more or less annoying. A little like if you are invited to the noisy party next door or not! Or whether you like the people!

One of the more mindblowing revelations, was the fact that recently, using ultrasound, we can actually listen to the sounds of plants growing, and in experiments done on maize, it’s been found that as a plant dries out, it generates ultrasonic signals, detected by special microphones. Plants give off sounds like high pitched squeaks when they need water! These experiments have lead to a whole science of agro-acoustics, for example, measuring the rate at which sap moves, using sound.

To wrap up the lecture, Goldsmith suggested the possible applications of sound and acoustics in the future. For example, ultrasonic levitation that comes from the packed force of the ultrasound. This could have great applications for useful things like invisible keyboards and possibilities of which now being explored for use in space stations. He touched on the use of acoustic microsurgery, using ultra high frequencies getting into dimensions less that the width of a molecule. At this stage, you begin to leave behind the idea of ‘sound’ as a wavelength, as the frequency increases and becomes higher. As various physicists like Einstein have touched on, the laws that govern the universe don’t match up with the laws of the atom, yet the study of sound may give us this bridge of understanding. Mindblowing stuff, indeed.

Reviewer: Lisa Williams

Irvine Welsh

As hordes of fans who have grown familiar with the distinct Leith vernacular within the author’s books streamed into Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, one could not fail to notice that the demographic of the audience was one in parallel to something of a Britpop reunion. Danny Boyle’s cinematic adaptation of Welsh’s novels Trainspotting (1996) and Paul McGuigan’s The Acid House (1998) were both hugely popular films at the peak of the Britpop zenith, and loyal fans of the writer are keen to hear what fate has become Begbie in the succeeding, post-Cool Britannia years. As I leant back to allow Still Game’s Gavin Mitchell aka Boaby the Barman in to take his seat, Welsh stepped out in front of the 350-capacity surroundings to rapturous applause, followed by radio presenter Janice Forsyth who was our hostess for the evening. The entire recording of this talk will be available to listen to on The Janice Forsyth Show on BBC Radio Scotland this coming Monday between 2 and 4pm.

In Welsh’s new novel The Blade Artist, the plot indicates that Begbie has removed himself from his ultra-violent past and moved to California as a reformed ex-con. However, the murder of an estranged son expels a red mist over our anti-hero and things quickly go from bad to worse. It was perhaps not entirely unexpected that Welsh would divide his story between America and Scotland considering that the writer currently lives in Chicago, returning to his homeland for two or three months at a time. In a climate when a number of people are pent up with frustration, Welsh remarked that Begbie was a “poster boy for anger and rage”, and described that the momentum from the afore-mentioned Big Issue story is what encouraged him to write The Blade Artist. Never wishing to spend too much time in Begbie’s violent mind, Welsh divulged that writing in the third person allowed the book to flow, keeping the reader in suspense about what would happen next.

It was fascinating listening to Welsh discuss the craft of his writing, describing himself very much as a ‘cut and paste guy’ rather than someone who can hand-write his novels. Sound advice to aspiring writers was dished out, encouraging them to ‘go out and engage with people’ and not ‘sit in being a fat bastard in front of your TV’. Confessing that he wrote part of Trainspotting whilst working between two offices at Edinburgh District Council, Welsh proceeded to cheerfully dissect exactly how a writer spends their time during an ordinary day. Forsyth’s endearing chatter and exchanges with the Edinburgh writer ensured that a friendly tone kept moving along as questions were posed by members of the audience. Arguably the funniest point of the evening was one question which asked how Begbie ever managed to get into America, causing Welsh to explode with laughter and admit that he hadn’t thought of that before slyly explaining that despite Begbie’s violent past, there were no drugs charges which would mean instant rejection.

It was fascinating listening to Welsh discuss the craft of his writing, describing himself very much as a ‘cut and paste guy’ rather than someone who can hand-write his novels. Sound advice to aspiring writers was dished out, encouraging them to ‘go out and engage with people’ and not ‘sit in being a fat bastard in front of your TV’. Confessing that he wrote part of Trainspotting whilst working between two offices at Edinburgh District Council, Welsh proceeded to cheerfully dissect exactly how a writer spends their time during an ordinary day. Forsyth’s endearing chatter and exchanges with the Edinburgh writer ensured that a friendly tone kept moving along as questions were posed by members of the audience. Arguably the funniest point of the evening was one question which asked how Begbie ever managed to get into America, causing Welsh to explode with laughter and admit that he hadn’t thought of that before slyly explaining that despite Begbie’s violent past, there were no drugs charges which would mean instant rejection.

With an enormous queue keen to have their books signed, pictures taken, and hands shaken, things were brought to a close after an hour. Welsh’s nurturing affection for his characters who were ‘simply going through troubled times in otherwise decent lives’ was commendable, whilst maintaining a contemporary feel for Scottish social issues, politics, and vices means that it is unlikely that this will be the end of the Trainspotting gang from a literary view; now isn’t that just barry?

——

Steve Orlando: The Midnighter

Steve Orlando reminded me of how much I generally like being around Americans. Straightforward confidence tempered with humility and empathy is a winning combo. And winning he seems to be; writing and producing comics such as VIRGIL, Undertow and Midnighter, as well as taking part in Batman and Robin Eternal and CMYK: Yellow at DC Entertainment. The crowd was quirkily niche and highly individualistic compared to other audiences; but as a whole, quiet and subdued in their respectful wait, they had to be encouraged to chat with each other. I suspected I was the one in the room with the most superficial knowledge of comics. Ann Louise, the school librarian who made the introductions, told me that greater numbers of libraries in Glasgow were opening up to comics due to demand from teenagers.