Uncategorized

Why you should let yourself be yelled a in a random club, 4 stories high

Liam McCormick, 4 Stories High, Spoken Word

23rd August 2016

Under the shadow of Edinburgh castle, down a cobbled staircase there is a club named Silk, where Liam McCormick paces the stage maniacally in hole-ridden high tops and a number two buzz cut, ranting lyrical about a host of characters devised from the twisted innards of his mind. It feels in that strange velvety room that a number of worlds have collided, that perhaps the fusty plush bubble built no doubt for the minted tourists and students who keep the Edinburgh economy afloat has burst for a moment to let less fortunate creatures in. Indeed for a half hour or so, the space was home to Tam, xxxx, and xxx – the characters at the center of Liam’s poems – each of whom is subjected to the destroying forces of the societal pressure, specifically bullying.

The stories are well told, and at moments beautifully crafted. McCormick brings an intensity and a commitment to his performance which is as uncomfortable and electric as his subject matter. He should be commended not just for his ability as wordsmith, but also as performer. When I listen to him I am jealous that I am not Scottish. His rhymes are gutteral, and his rhythms twist and turn into the sing song lilt of a bygone storyteller. How I wish that I could utter words with the thick rasp of his.

His is an energetic, albeit slightly unhinged show. It is not easy to sit in a room and listen attentively to one voice swell and fall for half an hour. But everyone should try it. Isn’t Storytelling one of the age old ways of experiencing the unknown? Where heard in the firelight in a forgotten age or the neon glow of a fusty night club, it is beautiful form, and one which when used to great effect can convey emotions more deeply and directly than perhaps any other form. Liam’s work certainly does, and he is a star on the rise in the world of Scottish spoken word. Isn’t the Edinburgh Fringe about trying something new? Exceeding what you know? Taking a chance on hidden gems, and fresh talent? People these days seem to say all the time that they mean to do extraordinary things, that they want to support creativity, and encourage the bravery of young artistic talent. Well, get your arse to Liam’s show then! Support him, listen to him, open yourself up to something different. It’s free, and it’s interesting, and you’ll end the show with a great big chuckle, emerging from the dark stairwell of Silk into the hazy shadow of the castle, the sun starting to soften, and the bustle of the Fringe waiting for you around the corner.

Support young artists. Support spoken world.

Get yourself out to something interesting for a change.

Reviewer : Charlotte Morgan

Jim Crumbley & Stephen Moss

Studio Theatre

EIBF

22/8/16

All Senter, in conversation with Scottish wildlife author Jim Crumley and Bafta award winner (Springwatch 2011) Stephen Moss on the launch of Crumley’s new book The Nature of Autumn . Describing the power of Autumn Crumley states in one chapter: ‘And the first day of autumn is the beginning of everything, the first stirrings of rebirth. The forest fall (it is better named in America than here) thickens the land with limitless tons of bits and pieces of trees. The earth is hungry for these, for they break down into food: all spring, all summer, it has been thrusting life upwards and outwards, and by the last day of summer it is tired. Autumn is the earth’s reviver and replenisher, the first day of autumn is the new beginning of everything and the last day of autumn is the beginning of next spring. Autumn is the indispensable fulcrum of nature’s year.’ Autumn it seems is the perfect fusion of form and function but , ‘nature is in big trouble.’ When Jim is asked why Autumn is his favourite season by Al Senter he simply and eloquently replied, ‘it’s nature’s state of grace.’

Having spent the entire autumn last year from as north as Harris to as south as Wigton this child of autumn gathered the necessary content of his book which is his widest interpretation of his title so far. Expect thoughts on his first sighting of a golden eagle reversing beautifully into its nest, studied by Jim for thirty years and now discovering that this piece of theatrical aviation had been denied to him till now. There is always something new to discover, to see or just to hear. Stephen Moss suggests to ,‘go out , stand and listen and close your eyes.’

It is heartening to hear Jim enthuse of the great Trossachs forrest, ‘ the scale of it is the sort of thing that can make a difference. It seems ironic that ecotourism and supermarkets came in the same year. 1959. While some were off to see the highlights of urban innovation the smart ones were osprey watching. They talked at length on the trial introduction of beavers in Scotland. Believing wolves would do more good than harm they advocate their return to our shores. Apparently elk do not behave elk like until a wolf appears when they suddenly discover a long lost ability to move at speed!

I learnt a lot about what is happening in the countryside north of here. So, what to look out for? Whooper swans, Scandinavian rushes, red deer ruts and aspen oaks.

Reviewer : Clare Crines

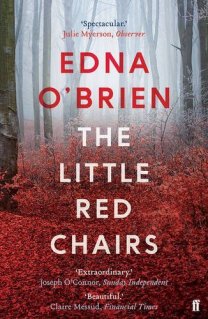

Edna O’Brien

Baillie Gifford Main Theatre

Edinburgh Book Festival

August 16

I felt genuinely thrilled and honoured to be sitting right up and close to living legend Edna O’Brien. Her cousin, also an O’Brien, happened to be sitting next to me, and she quickly offered up the story of when her first book came out in 1960, the infamous and groundbreaking ‘Country Girls’, the local priest called all the parishioners in to the Church one Sundaywith their copies of the book, created a large pile and set fire to the lot. It certainly didn’t stop her fervour to write. She hardly needed an introduction by chair Sara Davies, with her 17 novels, 9 books of short stories, plays, biographies and personal memoir.

At the risk of sounding superficial, at 85 she can always be described as elegant, poised and stately. From the way she scanned the audience, Edna almost looked like she’d rather have been at home or working on a new book, away from this expectant crowd, but she certainly didn’t disappoint. Razor-sharp, passionate and charming, her talk about her first book in a decade, ‘Little Red Chairs’, sped by. She began the hour by reading an excerpt, which immediately evoked the very particular atmosphere of a small town in Ireland. Clues in the passage create a sense of unease around the arrival of Dr. Vlad Dragan, healer and sex therapist. A beguiling man, who at first reels the townsfolk in with his charms, but then shows his true colours as a dangerous psychopath. He wreaks havoc on the town with devastating results, particularly for smitten Fidelma, the draper’s wife.

As it hinted strongly, the unsettling character is indeed based on Radovan Karadzic, the infamous Bosnian Serb war criminal. The title of the book refers to the more than ten thousand red chairs placed along the main street in Sarajevo, that represented the civilian victims of the war twenty years earlier, including little ones for the children. The idea for writing the book was sparked by a suggestion that stories often begin with the arrival of a mysterious stranger. For O’Brien, three necessary ingredients must be part of a recipe for a book; theme, story and the ‘seed’, that must all cook up together. She had to do a great deal of research to write this book, insisting that the only way to write about political problems was to know them from the inside. Along with the interest and the research, in order to really ring true, there must be a corresponding echo within oneself to explore the subject. She was fascinated by the common occurrence of charismatic, seductive people using manipulation for good and for bad; that they are often sides of the same coin, and I wondered how many she had come across in her personal life. Seeing the photos of the chairs, particularly the ones for the children, made her cry, and gave her the impetus to make sure her research was indeed thorough, including visiting The Hague. What bothered her most while gathering material was the total imperviousness of the war criminals to the magnitude of the crimes they had committed; responsibility and remorse replaced by repulsive swagger and bravura. She was shown the wing where Karadzic drank wine with his cohorts, and this sickened her.

As it hinted strongly, the unsettling character is indeed based on Radovan Karadzic, the infamous Bosnian Serb war criminal. The title of the book refers to the more than ten thousand red chairs placed along the main street in Sarajevo, that represented the civilian victims of the war twenty years earlier, including little ones for the children. The idea for writing the book was sparked by a suggestion that stories often begin with the arrival of a mysterious stranger. For O’Brien, three necessary ingredients must be part of a recipe for a book; theme, story and the ‘seed’, that must all cook up together. She had to do a great deal of research to write this book, insisting that the only way to write about political problems was to know them from the inside. Along with the interest and the research, in order to really ring true, there must be a corresponding echo within oneself to explore the subject. She was fascinated by the common occurrence of charismatic, seductive people using manipulation for good and for bad; that they are often sides of the same coin, and I wondered how many she had come across in her personal life. Seeing the photos of the chairs, particularly the ones for the children, made her cry, and gave her the impetus to make sure her research was indeed thorough, including visiting The Hague. What bothered her most while gathering material was the total imperviousness of the war criminals to the magnitude of the crimes they had committed; responsibility and remorse replaced by repulsive swagger and bravura. She was shown the wing where Karadzic drank wine with his cohorts, and this sickened her.

She tried hard in the writing of the book to remain both poetic but also true to the difficult material, in the spirit of Conrad, Hemmingway and the Kabuki Theatre when describing true horror. Her main character, Fidelma, who has the misfortune to be seduced by Dr.Vlad, ends up working at an advice centre for migrants and refugees, and she herself spent time at similar meetings, hearing terrible accounts, people checking out from the horror and waiting for the letters from the Home Office that determine their fate. What struck her was the raw accounts of horrors experienced; there being no time for anything but honesty after going through such terrible trauma.

After becoming the master of her craft after writing for so many decades, she had a great deal of wisdom to dispense to our eager minds. Every book you write changes you. The particular flavour that authors bring to literature depends on the accidents of geography and temperament, and knowing the landscape intimately means that your unconscious can summon details without thought. She despises clichéd, happy endings where all the loose ends are neatly tied up. Careful not to throw out a spoiler, she said the reasons for the story were encapsulated in the last two lines of the book; ‘the longing for home’, that we as humans are all born with.

For her the power of good writing is the precision that leads to intimate flawless communication; the truth of the words themselves and the effect the have on the reader. Don’t underestimate the power of your own experience mixed with your own imagination, she encourages us. Books, including the highly influential ‘Introducing James Joyce’ by T.S. Eliot, and poetry by Dickinson and Plath gave her inner faith and confidence to write. She describes her less than encouraging start to a literary career; a childhood in a house with only prayer books, Mrs. Beeton’s cookbook and bloodsport manuals to digest, and a family who equated her writing with sin. I’m sure we all gave silent thanks that she had the strength to break away from a stifling existence and continue to write, as she wryly repeated her publicists’ phrase, into her ‘ninth decade’.

Reviewed by Lisa Williams

Stewart Lee is more meta than all of these Eminems eating MnMs

Edinburgh International Book Festival

19th August, 2016

Apparently Stewart Lee wrote a column in The Guardian for five years. Did you read it? I didn’t. It’s a shame, because it sounds funny. If you’re cheap like me you could probably just google Stewart Lee Column Guardian and read some of them. But Stewart Lee wants you to buy his book. Its a collection of his “best ones” with bits added from the Guardian Comments Section – a smorgousboard of extremism, Lee-inspired satire, and the kind of things said by weirdos you overhear on the bus. It’s sort of like Jimmy Fallon’s thing where celebrities read mean tweets about themselves, but I think Stewart Lee came up with it first.

Lee is like the Borges of stand up comedy (if you don’t know who Borges is, then you’re probably the kind of person who hates pretentious literary references to Argentinian writers from the early 20th century who played with form and absurdity in their writing, namely by using things like dictionaries and encylopedias and the like to disrupt meaning blah blah blah yawn blah). I’m really proud of that analogy. Anyway, it was pretty cool to hear Stewart Lee talk about his book because (cue cuntish posh voice) as a writer and former English student, its like so fascinating to hear a comedian deconstructing comedy, and describing the way it relates to theatre and narrative.

But he didn’t do any stand up

I should have know that going in, because this was a promotional event about his book after all. It’s sort of like a meat eater going to a vegan restaurant and secretly hoping there will be bacon bits.

The event was good because Stewart Lee is a seasoned performer and genuinely very funny, but I don’t think there was as much chemistry between Ian Rankin and Stewart Lee as there could have been. If Ruth Wishart and Lionel Shriver were like Fry and Laurie, then Ian Rankin and Stewart Lee were like two strangers flirting badly on a bus. Book events are like that though. It was a good event, and I wrote a bunch of quotes down, but none of them seem funny in the cold hard light of my shit illegible handwriting. The Edinburgh Book Festival is cool because you see some of your favourite writers and public figures in a different light. But I do feel like the experience was similar to seeing Madonna photos before they’ve been airbrushed. You’re like, I knew she wasn’t that perfect, and I’m still impressed but you feel a bit weird.

Reviewer : Charlotte Morgan

We need to talk about rich people (and Lionel Shriver)

Edinburgh International Book Festival

20th August 2016

If you’re reading this, I’m guessing you are a vaguely liberal, young-ish Brit living in an English-speaking country who emotionally channel surfs between horror at the extremism of the Islamic State, and vague jealousy at the people having a better time than you on Instagram. On the one hand, you know shit is hitting the fan, but on the other, YOLO.

But every now and again, you remember: What’s happening to the world isn’t funny. It’s not entertainment. It’s a crisis.

Which begs the question: what to do? When you wake up in a Western country with a job, a life plan, and some kind of dependent organism (dog, baby, rat, ****friend), you can (a) choose to ignore the news; (b) cry over your organic muesli; (c) donate a small amount of cash to a charity that will employ numerous amounts of people to act in some way on your behalf; or (d) do all of the above.

Lionel Shriver seems to have sidestepped this great condrum by focusing on the economic timbomb hanging over the heads of the American people: debt. She believes that America is on the brink of collapse, that they have “seen the abyss, and are pretending that everything is fine”; and that if America goes, so will the world. Her imagination has been so capturd by this great fear, that she has written a book, The Mandibles, a novel which posits America in 30 year’s time: the economy has collapsed, and a President eerily similar to Trump in his policies has taken power.

By the looks of the sold out audience at Edinburgh Book Festival’s largest venue, and the scent of confused admiration eminating from the reviews, Shriver’s latest novel The Mandibles is doing something right. Firstly, it’s deeply engrained in the genuine fears of the middle class: rich people not being rich anymore. Secondly, it works hard to be as realistic as it is entertaining. It’s basically like a zombie film, but instead of being eaten, people lose their pensions. To be a successful writer nowadays, you do have to cater to a certain kind of clientel.

If it’s sounding by now that I resent the rich, aging generations who came before me and ruined my future, I really, really do. They’ve fucked the climate, the economy, and my EU passport. I’m really not happy. And, comically, Shriver identifies herself as part of this group. How hopelessly vindicated I felt, sitting in a room sponsored by a Financial Investment Fund and filled up with Baby Boomers in tweed being told by one of their own that they’d bum-fucked the millenials. Myself and two sweet-looking students were a minimum of 25 years younger than the rest of the audience. The people sitting around me looked rather awkward at this revelation; and then a plummy voiced fellow changed the subject via a question about the relationship between the “Chinese opium wars” and contemporary UK Policy.

If I’ve learned anything about the world through an hour with Lionel Shriver, is that Baby Boomers have the very great luxury of speculating about the near future, but they won’t have to live it. Shriver’s is a very specific kind of Speculative Fiction, one which is best digested from the comfort of a £1000 pound sofa in a house you own, filled with expensive coffee machines and Nigella Lawson cookbooks which magically transform middle class guilt into gluten free baked goods.

But I’ve also learned something else: they know. They fucking know!! They are beginning to understand what they have done. And there is not much left for them to do so they mock themselves through high-ish brow literature and BBC “Comedies”; they congregate in specially designated places for older people with disposable incomes and reap the remnants of their well-educated vaguely liberal sensibilities (namely book events, and Country File festivals).

If anything, Shriver is one of their leaders. A sharp, infinitely entertaining, and horrified middle class libertarian with two homes, and a big fat book deal. At the end of the show she was asked what role humor plays in a book which is otherwise so serious about the economic crisis unfolding in America. Her view on humor, she claims, is that it increases the tension; that it “twists the knife” and helps get her point across. But I wonder if it is, in fact, a release? A way for her, and her readers, to project their fear and guilt upon a future they will never have to live for a few hours, or a day, and then donate the book to a charity shop. Economic crisis is such a privilege. To fear losing security, you have to have it.

In summary: Shriver is sharp, witty, and brilliant at operating in double vision. Aren’t we all, these days?

Reviewer : Charlotte Morgan

Poetry @ The E.I.B.F.

Edinburgh International Book Festival

18th August 2016

—-

Poems are like little time-charts – they keep things safe

(Carol Ann Duffy)

—

It is a very good thing to be a poet, a very fine thing indeed. There are two types who exist on this Earth. There are those who roam the mountain wildernesses like lone wolves, howling to the moon & the wounded buzzard who has followed them from afar, from up high, observing them with a curious eye as the wolf howls laments to its slaughter’d pack each evening across the shrub-tussl’d plains. There are also the other kind, the ones caught as pups by the more adventurous fellows of Empire, taken back to the homelands & placed in confinement in zoos or parks for the entertainment of the natives, to be peered at & commented on as they pace their cage or compound in routine serene. The other day I found myself in a most sturdy donjon to see the latter sort on display, where the finest examples of the were placed before us for our entertainment. In the morning, we had the grand old dames themselves, the Lady Laureates of the UK & Wales, Carol Ann Duffy & Gillian Clarke, while evening gave us the winners of the Edwin Morgan Trust award for the best poet under thirty.

—

![3596936391_689c1b8e15_z[1].jpg](https://mumblewords.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/3596936391_689c1b8e15_z1.jpg?w=299&h=199)

The Lady Laureates read out some poems from their ouvre in a round-by-round fashion the first time in their lives they had been on the same bill. Introduced by Asif Khan – the new Duke of the Scottish Poetry Library – & accompanied rather cheekily by John Samson on various wind instruments – indeed, he introduced the ladies with a medieval sennet – it was a jolly good hour of sorts. Starting off slowly, Duffy grew into her performance with a growing magic.Her first efforts were more abstract word theatre than poetry, but when towards the end she read her poem invoking the 96 bells of Liverpool cathedral ringing out an unspoken elegy to the ghosts of Hillsborough, to the haunting chimes of Sansom’s recorder, I found myself consummately bewitched. Of her poems, the one about the counties of Britain, written in protest at the Post Office’s decision to phase-out county names on letters, was the most scionic from her soul.

But I want to write to an Essex girl, greeting her warmly.

But I want to write to a Shropshire lad, brave boy, home from the army,

and I want to write to the Lincolnshire Poacher to hear of his hare

and to an aunt in Bedfordshire who makes a wooden hill of her stair.

But I want to post a rose to a Lancashire lass, red, I’ll pick it,

and I want to write to a Middlesex mate for tickets for cricket.

But I want to write to the Ayrshire cheesemaker and his good cow

and it is my duty to write to the Queen at Berkshire in praise of Slough.

But I want to write to the National Poet of Wales at Ceredigion in celebration

and I want to write to the Dorset Giant in admiration

and I want to write to a widow in Rutland Advertisement in commiseration

and to the Inland Revenue in Yorkshire in desperation.

But I want to write to my uncle in Clackmannanshire in his kilt

and to my scrumptious cousin in Somerset with her cidery lilt.

But I want to write to two ladies in Denbighshire, near Llangollen

and I want to write to a laddie in Lanarkshire, Dear Lachlan …

But I want to write to the Cheshire Cat, returning its smile.

But I want to write the names of the Counties down for my own child

and may they never be lost to her …

all the birds of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire…

—

Gillian Clarke was more consistent, a wee tour de force of her life & lands, she had the more poetic voice of the two, & more variety in her themes. There was one poem in particular where gawp-lipped Duffy was sat transfixed on Clarke’s every word. After hearing the magnificent lines, ‘He hammered stammered words in the hallowed air / Of the House, an Olympian among them,’ I just had to find out more about the poem & cobbled Clarke in the press room – she told the Mumble that in her role as Laureate of Wales; ‘Though not obliged to accept a commission I am usually tempted. My favourite early request came from the Bevan Society for a poem to celebrate the sixtieth birthday of the National Health Service. Its creator, Aneurin Bevan, was a hero in my childhood home. Here’s ‘A Sonnet for Nye’.’

London was used to trouble from the Valleys,

People who lived close, loved song and word,

Despised the big men’s promises and lies.

With them the socialist vision struck a chord.

Colliers, who hated class and privilege,

Whose work was filthy, dark and perilous,

Spared a portion of their paltry wage

To pay a stricken neighbour’s doctor’s bills.

They sent their man to Parliament. Who dares

Wins. A fierce man with a silver tongue,

He hammered stammered words in the hallowed air

Of the House, an Olympian among them,

Stuttering his preposterous social dream

Translated from ‘a little local scheme’

After the Laureates I enjoyed a rare sunny day in Edinburgh, returning to Charlotte Square in the evening for the final of the Edwin Morgan prize. This is its third incarnation, & when £20,000 is given to the winner tax-free, it has shunted itself into the forefront of British poetry awards. Morgan died in 2010, & his nationalistic legacy, his ‘conceptual universe,’ included a trust to award, biennially, the best lapped up the verve of the modern world, the sizzling energy in its expression, & would have been happy to hear that this year, a certain young Aberdeenshire lassie called Penny Boxall – Education Officer at Oxford’s University Church – won the award for her first collection, Ship of the Line.- I agree, & wrote the word TALENTED in capital letters by her name as I was taking my notes.

Judged in tandem by Jackie Kay, Scotland’s Makar and Stewart Conn, former Edinburgh Makar, the work of all six of these youthful & illustrious Parnassia palustri was of a great standard – from the genuinely authentic doric of Orkney-born Harry Giles, to the wondrous poetic voice of Stewart Sanderson, who, one expects could handle an epic in his maturer years. Of the winning poet, Kay told the Mumble: ‘Penny Boxall runs a tight ship. Her poems are beautifully crafted. Reading her is to go on an interesting journey of exploration—stopping at fascinating places along the way. She has a curator’s mind and is always putting one thing beside another in an unexpected way.’ Here is one of her poems, the subject of which is three separate shipwrecks off the shores of Wales whose lone survivors shared the name Hugh Williams.

Judged in tandem by Jackie Kay, Scotland’s Makar and Stewart Conn, former Edinburgh Makar, the work of all six of these youthful & illustrious Parnassia palustri was of a great standard – from the genuinely authentic doric of Orkney-born Harry Giles, to the wondrous poetic voice of Stewart Sanderson, who, one expects could handle an epic in his maturer years. Of the winning poet, Kay told the Mumble: ‘Penny Boxall runs a tight ship. Her poems are beautifully crafted. Reading her is to go on an interesting journey of exploration—stopping at fascinating places along the way. She has a curator’s mind and is always putting one thing beside another in an unexpected way.’ Here is one of her poems, the subject of which is three separate shipwrecks off the shores of Wales whose lone survivors shared the name Hugh Williams.

Williams, Who Lived

When this man was hauled from the foam

and, shaking, asked his name, the news spread fast.

They skimmed him back to shore –

a talisman, breaking the waves like eggs.

Hugh Williams had lived before. The name

confounded shipwrecks, made men float

through salted depths towards the aching

light. Williams was a lonely but a living sort.

It seemed the surest way to last gulp air not water,

to die dry, was to be him; or if not him

another of his kind. The parish registrars

scrawled Williams upon Williams as though they kept

forgetting. Williams married Susan, married

Mary, married Anne; and when he died,

(and died – and died -) the headstones

read the same, like yesterday’s paper.

Williams stayed at home and picked rocks

from the binary of ploughed earth.

Or travelled, wrote a book, did

or did not like onions; wet the bed.

And when he went to sea – as captain,

passenger, stowaway – he kept himself

to himself; threw his name around him,

vein-strung, tenuous as a caul.

‘The muse is in very good hands,’ said Conn at the awards evening, & I very much have to agree. The future of poetry is guaranteed, for in the sanitised labratory environments of such places as the modern poetry world & its awards, the genes of the older specimens can be passed down more safely to succeeding generations without risk of contamination. And so the song plays on…

Here’s a poem by me – Damian Beeson Bullen – your reviewer – written during the Morgan awards

***

Sonnet : Composed at the EIBF Edwin Morgan Awards 2016

–

A gift it is to leave a legacy

Decanting lipless ghosts into a room,

To wander with rapacious clemency

Among the pearl-eyed maulers by the tomb.

–

Drawn to this fabric garden of the North,

Of soft retiring voices on the green,

They sing to me, this sextet, funell’d forth

Thro’ judges sate admiring, smiles serene;

–

They speak to me, these paragons of youth

In lyrical semantics, midnight-hewn,

From dreams they fashion’d poems, born from truth

Unfetterd by this pure, presaging moon

–

O bauble gleam… thro’ dark, serrated skies…

Thro’ hearts endors’d… vault from aerated eyes!

Darren Shan: Tales of the Undead

Roy Hattersley

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Baillie Gifford Theatre

18th August 2016

Throughout Roy Hattersley’s talk I was tweeting. Now, this isn’t something I would normally do during an event, but he was so quotable that I couldn’t resist. What this involved, however, was taking some flak on Twitter for the views expressed, as what I was saying started to get around to politically-active tweeters. The name ‘Jeremy Corbyn’ was mentioned once or twice, for example, and that drew fire. I had to point out that I was quoting verbatim from a live talk by Lord Hattersley at the Edinburgh Book Festival, and that just as in any talk, what was being quoted was the opinion of the speaker, not the reporter. If this illustrates anything, apart from the fact that passions are currently high in the Labour camp, it is that Roy Hattersley’s talk ran off-topic by about half-way through. It was supposed to be a reappraisal of Harold Wilson, whose centenary is this year. With a full auditorium of people themselves engaged with the politics of the day, it did not take long for that reappraisal to lose momentum and to veer off course.

For the first few minutes of the talk, I wondered whether I should treat it as a comedy routine, giving it stars for material, delivery, and laughs, because funny anecdotes came thick and fast. This was only the case, however, during Roy’s accounts of early meetings with Harold Wilson. Towards the end things became a little more sour. I should point out that Roy Hattersley is now markedly elderly. This isn’t a fault, it’s an inevitability, but it does mean that his voice began to fade long before his hour was up, and even with amplification he became difficult to hear at the back of the theatre. This didn’t help matters.

He described Harold Wilson as “clever, industrious, and quirky”. What instantly sprang to my mind was a quote attributed to Nichloas Kaldor, who was an advisor to the Wilson government of 1964: “People think Harold is extremely nasty but extremely clever. In fact he is extremely nice but extremely stupid.” Now, I’ll add the caveat here that I only have my own recollection of that quote to go on, so I can’t support it with a reference; even the mighty internet can’t back me up, so please just take it for what it’s worth – a possible difference in opinion between two men who knew Harold Wilson fairly well.

Roy recalled an early experience of speaking before an assembly of the Labour Party. He couldn’t understand why he was attracting laughter, until he found out that people thought he was doing an impression of Harold Wilson. Indeed, Wilson was a gift to impressionists! Roy described the 1964-1970 Labour government as ‘the most socially-progressive government of the twentieth century’, with measures such as the abolition of the death penalty and the legalisation of male, adult homosexuality. To him it was less socialist in ideology than the Atlee government, but infinitely more socialist than the Blair government; Tony Blair was, or is, a kind of socially-progressive Conservative, apparently. On two matters directly to do with Harold Wilson he was adamant. Firstly that there had been no affair between Wilson and Marcia Williams. Secondly that the reason Harold Wilson resigned in 1976 was that he was seriously ill, and was suffering from memory problems associated with the onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

The moment that the talk began to turn sour was when a questioner drew Roy back to his mentioning the strength of the Wilson cabinet, when it had people like Barbara Castle, Roy Jenkins, Anthony Crossland, and Denis Healey in it. Where, the questioner wanted to know, were the people of this calibre in the current Labour party? What this drew from Roy was words to this effect – that back benchers are better and more committed than they were in his day, and that he could name half-a-dozen or more Labour back benchers that would make a good Prime Minister. Fair enough. When asked who he thought should be the next leader of the Labour Party, he named Owen Smith without hesitation…

Here I am going to insert a declaration of total disinterest. I am not a member of the Labour Party, nor of any other party, and I do not have a say in whom they will choose to lead them. Out of Smith and Corbyn I know whom I like better as a person, but that is in itself of little relevance.

… anyhow, to continue. “People queuing at food banks need a Labour government,” Roy declared, “Jeremy Corbyn is unelectable.” Now, this is a mantra I’m sure we have all heard repeated and repeated, and about which we all have our own opinion. However, what is ironic is that Roy Hattersley repeated it on a day on which, in a BBC debate between Smith and Corbyn, the latter ‘won with the undecideds’ in the audience (according to Ayesha Hazarika). Winning with undecided is what being electable is all about, or am I missing something? “People who support Corbyn have never even seen a food bank,” Roy went on. Now that was the nadir of his presentation, it was a gratuitously offensive and appallingly condescending remark. How does he know with that precision what the demographic of Jeremy Corbyn’s support is? I would bet that many of them have indeed seen a food bank, and if they are not necessarily amongst those who draw upon it they will include people whose social conscience causes them to deposit in it! As do a lot of very ordinary people, Roy – people like me!

Okay, it is time to give him due credit. He might not have endeared himself to me by the end of his talk, but it was a full and informative one. He had drawn a full crowd and received warm applause. Would I go to see him again if he was to appear here at the Book Festival? No. As simple as that. No.

Reviewed by Paul Thompson

Sharon Blackie: A Journey to Authenticity and Belonging

Michael Scott

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Studio Theatre

17th August 2016

—

The Studio Theatre is a much more intimate venue than the Baillie Gifford. My favourite perch (stage left, top of the stairs) is a lot closer to the dais. The ventilation system still roars, but you learn to put up with that at the Book Festival. Journalist and critic Stuart Kelly introduced us to Michael Scott, who actually needed little introduction, as he is a well-known face from historical documentaries on TV. If anyone demonstrates that there is a future for you in history, if you are relatively young and personable, then it is Michael Scott. There is a fascination with bygone civilisations, documentaries on cable TV channels every night, and even on the day of Michael’s talk there was an article in The Guardian about Cahokia, the pre-Columbian city on the Mississippi. The time is ripe for the slim and the good-looking to have footage of themselves taken treading thoughtfully through ancient, sun-drenched rubble, with their own awed commentary playing.

Michael’s book, Ancient Worlds: An Epic History of East and West, from which he read a twenty-minute excerpt, attempts to demonstrate the συμπλοκἡ – ‘symploce’, the interweaving and interconnectedness – between the large empires and civilisations that sprang up in the first millennium BCE and into the first CE. He spoke to us of Antiochus the Seleucid Emperor, of Hannibal, of Philip of Macedon, of Diodotus king of Greco-Bactria, and of Zhao Zheng (Qin Shi Huangdi) king of Chin and first Emperor of a united China. These were all relatively young leaders, with new ideas, existing in a world where these vast territories were known about, where the idea of ‘world domination’ was conceived, where a global picture was first formed. These Empires were not necessarily alike; for example, the Chinese Empire was founded on uniformity, obedience, and standardisation, all of which were strictly enforced, whilst the newly-emerging Roman Empire tended to be syncretic, to dominate by adopting what it found. In the world that Michael presented to us, war was a shaper of history and culture, and history itself, which was being documented, was a lesson for the ruler and potential ruler. “You can’t govern in China without history in your mind,” was an established axiom that Michael quoted and drew upon.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FqnBBjC_8no

His delivery was that of the TV documentarian, as you would expect. The history on offer today was very much a case of ‘Names, Dates, and Greats’, which until recently has been a denigrated approach. What has focused historians again on the broad issues of history is the fact that we are, today, very much aware of global issues, of globalisation. This was a trend which, he thought, had been growing since the First World War, a conflict that had involved peoples from many continents. I pointed out to him that he had dealt with very broad issues, and asked whether he had any sense of the fragility of history, of small things – the stumbling of one soldier, the decision of Genghis Khan to come out of his tent and turn left instead of right, the historical ‘butterfly’ effect – that might radically affect these apparent broad historical movements. He replied with a couple of examples. Firstly, how the introduction of direct democracy in ancient Greek city-states was an accident, brought about by a split in a ménage à trois. And secondly the visit of a few ‘Roman ambassadors’ to the court of the Emperor of China. No one really knows whether these ‘ambassadors’ were genuine envoys or a group of chancers, but what is known is that their banal gifts to the Emperor did not impress him, and he sent them away with a flea in their ear. Michael said that if they had ‘done their homework’ and bothered to find out what the Emperor really valued, they could have brought about a completely different relationship between two empires at the extremes of the known world.

This was a fascinating presentation. Michael Scott spoke with great clarity and was very attentive to questioners. If there was a down side, it was that his PowerPoint maps were not very clear. If he didn’t actually invent the term ‘Game-of-Thrones-esque’ he is the first person I ever heard use it. And indeed it seemed appropriate, because you could take any of the real persons he talked of – from Qin Shi Huangdi, to Diodotus, to Hannibal – and substitute the names Stark, Lannister, Bolton, Baratheon, or Targaryen with ease. It is that which made his talk primarily an entertainment, although an informative one. This is a problem that Game-of-Thrones-esque history has to deal with – the conflict between necessity to have detail and hard fact in historical study, education, and presentation, whilst dealing with broad, global issues in a palatable format. That’s the area Michael Scott operates in, and the line he walks.

Reviewed by Paul Thompson