Uncategorized

Magnus Mills – The Vinyl Countdown

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Garden Theatre, Charlotte Sq.

14th August 2017

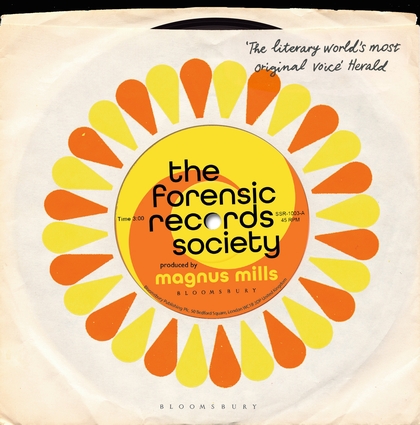

“When Gregor Samsa woke up one morning from unsettling dreams, he found himself changed in his bed into a 12-inch LP.” Well, no, not exactly. Though I have to say that if an event is touted “High Fidelity meets Kafka” that’s what I would expect. In fact Magnus Mills’s ninth novel, The Forensic Records Society, starts with Keith Moon’s off-mic shout of “I saw yer!” from the end of The Who’s ‘Happy Jack’, or so he told us today in the Garden Theatre.

When I visit the Book Festival I like to go to events about books I haven’t read. That way I know that if I want to read the book by the end of the event it has been a success. I haven’t read The Forensic Records Society. So do I want to?

Magnus Mills was introduced to us by broadcaster Joe Haddow. In contrast to Joe’s genial scruffiness, Magnus appeared as a tall, lean, unsmiling, quiet-spoken, suit-buttoned-up wight. That was a front. There’s a dry wit lurking not far below the surface. There’s also a man who knows vinyl, who knows how long ‘Complete Control’ by The Clash lasts, who has a collection of nine hundred vinyl singles all filed alphabetically. He’s a man who knows vinyl geekdom first hand.

Although Magnus says that The Forensic Records Society comes from his imagination, not his experience, that the pub in which the eponymous Records Society meets is not actually his local – the Pineapple in Kentish Town – and that the characters who haunt the novel are not based on anyone he knows, I am certain that there must be one or two knowing winks here and there. The book’s basic premise is that a handful of enthusiasts start a record club in a private room of a pub. The club has very strict rules, its founder, according to the event blurb in the Festival brochure, is a man of uncompromising dogmatism. When a second record club – The Confessional Records Society – is set up in the same pub on a different night, and is more arcane, more impenetrable than their own, their narrow microcosm begins to experience a power-struggle. Magnus has certainly come across the kind of defensive/counter-offensive dogmatism he portrays, if we believe what he says about someone’s reaction to a casual remark:

“I just said I thought the White Stripes were just messing about most of the time […]

I felt like I was in court!”

Magnus read some extracts for us, and in between slipped a couple of 45s onto a fifty-year-old deck he had brought along. ‘Waterloo Sunset’ by The Kinks, that was fine, but Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Man Of The World’ developed ‘wow’ and had to be taken off. No matter, as the extracts from the novel were intriguing enough. He has a style of writing that, if I didn’t know better, I would say hadn’t changed since he was about sixteen and was still trying to impress us with the way he handled the English language. There were no contractions, no couldn’t, no wouldn’t. Characters didn’t ask, they “demanded.” A character “adopt[ed] a casual manner,” or “offered words of consolation.” The dialogue was full of bewilderment and awkward pauses. But that worked! It all seemed to fit the narrative voice of the novel, and to be just right to express obsessive geekery. Magnus owned up to having “a sarcastic manner,” and it showed in the extracts he read out. That also reinforced the impression that it is a very ‘male’ novel – most of the characters are men – but that seems okay, as obsessive hobbyism tends to be a very ‘male’ thing, as Joe Haddow pointed out. In any case, Magnus says, he doesn’t really understand women, so why do them the disservice of writing about them from a position of ignorance.

Magnus Mills was brought up in a family where the paterfamilias did not believe in and did not allow commercial broadcasting – there was no ITV, no Radio Luxembourg, certainly no Radio Caroline. In a way Magnus has steadfastly refused to move on, he does not own a CD player. Just those nine hundred singles and fifty-year-old deck with wow. Joe Haddow reminded him that vinyl records were making a comeback, and he said that he had bumped into a teenage girl in the street:

“I said, ‘Oh, you’ve got a record player’, and she said ‘Yes’. I didn’t know what to say next.”

So do I want to read The Forensic Records Society? Yes, I rather think I do. Further than that, notwithstanding its being full of male characters, I’m going to recommend it to my wife. Those awkward pauses in the dialogue remind me of a Discworld novel, and she likes those. Ha! Discworld! See what I did there?

Reviewed by Paul Thompson

Luka Lesson, Jenny Lindsay, Omar Musa and Michael Pedersen: The Poetry of Performance

Edinburgh International Book Festival

Bosco Theatre

12 August 2017

This event was a one-off event for the Edinburgh Book Festival as part of their series Babble:Spoken Word. It was the result of a week in May of intense collaboration between Australian poets Luka Lesson and Omar Musa and local Scottish poets Jenny Lindsay and Michael Pedersen, now fully developed into an electrifying performance. They had already shaken us up with their teaser at the Scottish Poetry Library in May, and didn’t renege on their promise of a bigger, bolder, polished show on the opening night of the Festival.

Jenny Lindsay, well loved on the Edinburgh and Glasgow poetry circuit with her Rally and Broad events series, starts with a wry piss take of ‘Edinburgh, oh Edinburgh’, with a knowing sigh and sarcastic weariness. She threw the first of a few well-aimed jabs at its contradictions; ‘dreadlocked fire eaters alongside a career in buy-to-let’, Edinburgh, the ‘old tart’, prostituting itself to American tourists with its packaged history on the Royal Mile. And so begins a night of magic journeying through life and lands, as each poet takes a turn on the mike, again and again, the four comrades arm in arm, skipping down the yellow brick road.

Jenny is the warrior woman, the person whose words empower you to throw off your artificially crafted burden of femininity, your ‘box of false womanhood’ and reveal yourself in all its fullness. Omar is the lover; seductive in his handsome sturdiness with tender odes to the freckles on his beloved’s face, turning ‘fireflies at night’ in his poem ‘Lantern’. Michael is the jester; his frenetic energy spitting out of his wiry frame and high top hair, with perfectly timed, quintessentially Scottish punctuations of self-deprecation. And Luka, the High Priest, staring into the infinite, and taking us all with him on his mythic quest to find Self. They would resist these simplistic labels, rightly, as they all share these characteristics in their own defined and unique ways. Each one sharing a common human story of struggle; telling their stories with expletives, wild tenderness and jokes.

Jenny savagely mocks the middle class making art out of others’ suffering; those looking to find prettiness in others’ poverty, a young girl stuffed full of fish fingers and CBeebies singing somewhere over the rainbow’. Contrasted with these poets who do it right; as they bring us the real beauty in suffering, plunging and probing into the heart of our tough realities. She brings forth some wry laughter with her acute observations of modern predilection for dating at arms length as a text bounces in at 1am with ‘I promise I won’t fall in love’, juxtaposing it with the miserable, desperate ‘glory days’ of lifelong marriage. Michael, whose performance and power racked up several levels since the original, tentative reading at the Scottish Poetry Library, rapidly fired a cannon of finely crafted images onto the screen inside our minds; from junkies to vicious birds at a BBQ, passionately letting us see the underbelly of Edinburgh in a new light. Breathlessly talented with words, he’s expert at playing with pauses, to create pathos and great comic relief.

My favourite one from Omar is his journey to a planet where everything is perfect; his first love still loves him, his father plays without a hint of malice, and best of all, he can understand his grandmother perfectly as she speaks to him in her mother tongue, Malay. We hope this is a version of the promised heaven waiting for us all. All the poets share a common struggle of fighting different types of marginalization, and as they share their fight to come from the margins to the centre, the power of their voices comes from it being very much on their own terms. They are angry because they love. Truly loving anger is a rare thing, but this is the special experience we were fortunate enough to witness.

Luka bestows on us a touching new poem, ‘I killed a man’. Like Omar’s rise from his tough home town of Queanbeyan, where boys ‘get hard at the thought of carnage’, managing to keep his heart open along the way, Luka shares his inner transformation as he walks the age old journey; shedding the old restrictions to newly embrace what was inside him all along as he ‘healed a man’, in a cave in Greece, the home of his ancestors. And what glorious ancestors they were, as he invokes their presence to call on their strength, positioning himself in the long, unbroken between them and his imagined great-great-great-great-great granddaughter. Luka’s respect and love not just for his ancestors, but the land and the original people of Australia despite and, importantly, because, of the existing power structures’ attempts to ‘colonise, compromise and conflict me’ shines through his whole being. Like a true mystic, as he looks into the distance but flickers a warm smile over the audience, he exhorts us to see beyond our twisted histories and false sense of separation, and live as our divine selves.

Sometimes poetry can feel self-indulgent and pointless. But as the night’s themes spiralled around from childhood, to love, to loss, to dreams, to personal and common struggle, these poems felt vital. Not just alive, but vital to our sense of feeling. Vital to our sense of connection. The same struggles, same hurts, same hopes, from human beings coming together from thousands of miles apart, reminding us we’ve been doing this for thousands of years. Like the fireworks firing away up at the Castle between and around the poems, those carefully chosen words and crafted phrases took turns to sprinkle over us like fairy dust or pepper us like mini shrapnel. Jenny and Michael we can catch up with again in Scotland, thankfully, but our Australian preacher-priest-poets have to fly away, leaving behind their trails of tales…..As Omar and Luka share the stage to end with their hip-hop influenced poem-song, ‘The Light’, we we know we’ve been privileged to have shared a truly moving and transcendent experience.

Reviewed by: Lisa Williams

An Interview With Magi Gibson

Hi Magi, where ya from & where ya at, geographically speaking?

Hi Magi, where ya from & where ya at, geographically speaking?

I was born in a castle on a hillside, with high stone walls and a magnificent wood-panelled entrance. One day it metamorphosed into a university with white swans on a beautiful loch. It sounds like a fairy tale, but it was real life in Bridge of Allan, Scotland. OK, at the time the castle was being used as a maternity hospital, and I was only there for a few days before I was brought home to the small mining town of Kilsyth, 11 miles north of Glasgow. An ex-weaving town, with a strong socialist tradition, the pits were already closing down as I grew up. I walked past huge black bings to go to primary school. My childhood there growing up in a council house shaped me. I’ve lived a lot of my life in and around Stirling and Perthshire – with a year in Paris – and I now live in Glasgow.

When did you first realise you were a poet?

1985 I realised it was a possibility. I’d just started writing and I read the first poem I ever wrote at an event to celebrate the contribution of miners’ wives to the miners’ strike. It was in Stirling Miners’ Welfare Hall and there were about 200 people squeezed in. I was terrified. The poem, “My Father’s Dungarees” is essentially about shame, bullying and pride. They loved it and took the copy I’d read from and pinned it up behind the bar. The connection with the crowd was electrifying. Personal and political. I knew instantly I wanted to do that again.

Which poets inspired you at the beginning & who today?

When I was wee, we had a huge, old family book of the complete works of Robert Burns with copperplates and I was allowed to put it on the table and read it. I loved rolling the Scots words around in my mouth. At secondary school I loved the Romantics. But as a woman, reading the Polish poet Anna Swir was pivotal. The way she writes about the female experience, from the body, as if it’s universal, with such a quiet, pared-back quality, yet such depth. Other favourites are Sharon Olds, for her dark wit, Adrienne Rich for her subversive wisdom and daring structures. Norman MacCaig for his off-kilter way of squinting at the world. Anne Sexton for her courage. At the moment I’m going through a wee love affair with Imtiaz Dharker. I love the musicality of her lines.

You are a widely loved & read poet along the length & breadth of Scotland, Magi Gibson. Your works have been published by all the main Scottish publishers. Can you tell us about the poetry scene in your native land?

You are a widely loved & read poet along the length & breadth of Scotland, Magi Gibson. Your works have been published by all the main Scottish publishers. Can you tell us about the poetry scene in your native land?

It’s vibrant and varied and poetry thrives in Gaelic, English and several varieties of Scots. Like many poets I can be relatively reclusive, but the Internet lets me peek into corners, and I’ve travelled extensively. There are a lot of poetry communities in Scotland’s main cities, from rap to spoken word to page poets. Writing in every form imaginable. And lots is happening in more remote areas too. I’m always pleasantly surprised when I get an invite to Peebles or Skye. (Note. It’s been a while. How about asking me back?) And, of course, as well as community groups and on-line groups, universities now run creative writing courses. All very changed from when I was first writing and you were lucky if you could find a local writing group with members under the age of 90. We’ve lost some of the best paper magazines from years ago, like Cencrastus and West Coast Magazine. Chapman is all but gone, and it looks like Gutter will disappear, both of which will leave a big hole at the quality end of Scottish publications. But we’ve gained The Poets’ Republic, with its Gaelic section, and we still have Northwords Now, and Pushing Out the Boat which I was founding editor of in the north east in 2000. I’m sure there are others I don’t know about. I don’t keep a close watch. And there are on-line magazines like Glasgow Review of Books with its interest in poetry in translation. In years to come I imagine this will be seen as a very vibrant time for Scottish poetry. Partly because of the turbulent political times we’re living through. People have a lot to feel uneasy about. A lot that needs expressed, and poetry is a good means to do that. But partly because poetry has been given more prominence by posts such as that of Scottish Makar and the Makarships of cities like Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Stirling, where I was Makar for three years.

What drives you to create a poem?

An itch in the soul. Something snagging on my consciousness, that I can’t shake free. It might be something glimpsed that’s achingly beautiful. Or something that happens that disturbs me, something I can’t resolve in any other way than working it through in a poem. Anna Swir said, “The poet has a conscience with room to grow. What does not, as yet, shock and outrage others, shocks and outrages her.” A lot of my poetry bursts from that initial shock to my conscience. Like the poem, West End, Friday Night, when I almost ended up in a punch-up trying to save a young woman from being mugged. Other poems burst through from a love for humanity, like Mother and Child, about a young woman breast-feeding in an art gallery. Some are deeply personal, like My Mother’s Funeral, yet I know from poetry readings, that that poem touches many people deeply.

Early Morning Train to Inverness

from time to time snow sprinkles from the sky

the way flour sifts from a baker’s fist

grey steel pylons pose like giant girls

playing ropes

gorse, dark bottle green, bristles in scruffy tufts

on a badly shaven chin of hill

a woman in a suit tap-taps at her laptop

in communion with the shimmering screen

scots pines turn their Presbyterian backs

on a stream that pishes like a drunk

a lochan slate-grey bides her time, swollen-bellied

in February, her waters will break in March

a woman paints her nails, the air

thickens with the reek of varnish

Slochd summit snow, a crumpled duvet

chucked on the chittering land

Look! Look! A red stag with forked lightning antlers

poses for a tourist’s pointing finger

a mobile phone skirls Scotland the Brave

between peaks that rise like stony breasts

a yellow lorry carrying eggs, races the train

as packed like battery hens we hurtle on,

we hurtle on, we hurtle on, towards breakfast,

and you, and Inverness

What does Magi Gibson like to do when she’s not being poetic?

I used to be very sporty, running 10Ks, and when I was younger playing basketball and doing lots of dance and exercise classes, but ill-health has put a stop to such excesses. Now I read a lot, with spates of bingeing on novels. My husband (Ian Macpherson) is a former stand-up and now writes books. We both work from our small west end flat, so our days are organised around each other. Chaotically. With much laughter involved. We’re a bit like two children happy in our imaginary world. Which includes an imaginary cleaning woman, Hilda, who forgets to Hoover or dust, but hits the gin hard. We go walks each thinking the other is leading, and we end up lost. We drink lots of pots of tea. (Loose-leaf Assam, for the aficionados.) We enjoy having to go to book festivals both here and in Ireland, and we go off to the Highlands for what we call writing retreats when we can.

Can you tell us about the Wild Women Writing Workshops you host?

I was asked to pitch an idea – something a bit different – to West Cork Literary Festival in 2011, and ‘Wild Women Writing’ based on my poetry collection, Wild Women of a Certain Age, seemed a perfect fit. The three day workshop not only sold out, it was over-subscribed, with women driving for over an hour on the first morning in the hope of a stand-by place. We extended it to five days to accommodate the demand. And that was it. The concept was fully born. I run the workshops over three or five days at a festival, or as an eight or ten week block. Sometimes I do a one-off ‘taster’. Each workshop is designed to unlock creativity and remove blocks that may have been holding the writer back. We may well cover the craft of writing, and how to get published, but that’s not the primary aim. The primary aim is to produce new and different work, for the writer to challenge and surprise herself. The workshops are always sold out, and deliver very positive results. Sometimes women get in touch years later to update me. I hold them only intermittently though, as they drain a lot of my own creative energy. In order to lead them I need to respond to the dynamic of the group as well as the needs of the individuals as much as possible. Each of the women will have a different starting point and a different writing goal. It’s a creative journey I ask the women to come on with me, so it’s not a set pattern where I can say in advance exactly what we’ll cover. Though I can say that all source material will be from women artists and writers and there will be laughter and surprises along the way.

What are, for you, the differences between poetry written down & performance poetry?

I like my own poems to work, as far as possible, both on the page and in readings. I do perform well, and can hold my own on any stage, but I’m not a performance poet. The joy for me in going to poetry readings, which I did as much as possible when I started writing, is always to hear the poet’s voice. I remember early on hearing Norman MacCaig, Ian Crichton Smith, Edwin Morgan, Tom Leonard. When I read their poems on the page afterwards their voices sang back to me, adding an extra dimension. And later I read on platforms with them all. Performance poetry seems to me to be a more high voltage affair. More of a theatrical experience, a word-lovers’ comedy/cabaret cross-over, an emotional roller-coaster of an immersive crowd experience. But sitting quietly at home with a book, and a lamp, and the curtains closed, reading a poem, that is such a still, private pleasure, and suits me in my introvert state, the syllables and sounds dancing in the brain, the images spooling behind the eyes to the rhythm of my own quiet heartbeat. And after, letting the poem connect with my own life experience, the thoughts reverberate, sift and drift… And, of course, there is a whole skill to getting the poem to sit on the page so that the tension of the line works the way you want it to against the white space, so it reads back the way you want it to in the reader’s head. That’s a whole other challenge.

PATRIARCHAL CONSPIRACY #53

when I type in feminist

it autocorrects.

now my T-shirt reads

this is what a fantasist

looks like

What does the rest of 2017 hold in store for Magi Gibson, the poet?

I need to wait quietly and make space for poems to come creeping up on me.

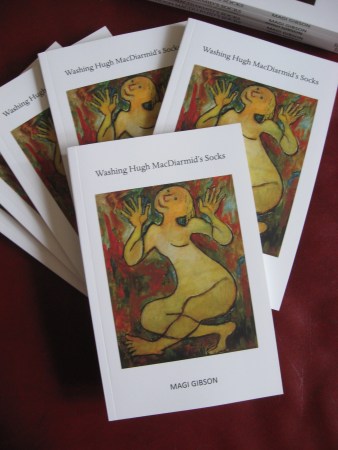

There will be more readings from the new collection. There’s lots of parts of Scotland I’ve still to talk Hugh MacDiarmid’s Socks to! There will be many more cups of Assam tea. And the first Wild Women Writing Workshops in quite some time. I’ll be setting dates for them very soon. I’m headed to Aberdeen on Saturday 12th August, 7.30pm for a poetry reading hosted by The Poets’ Republic at The Blue Lamp where I’ll be reading with Northern Irish poet, Matthew Rice, one of the ‘best new British and Irish poets 2017’. And I’ll be reading and discussing poetry and writing and politics at two events on Tuesday, August 22nd at 1.45pm and 3.30pm at the Edinburgh Fringe at ScotlandsFest. Venue 40 • Quaker Meeting House 7 Victoria Terrace, Edinburgh.

An Interview with Christine de Luca

Hello Christine, when did you first realise you were a poet?

Hello Christine, when did you first realise you were a poet?

I suppose I started writing poems when I was about 30, when I realised that there was little chance of returning permanently to Shetland, where I was born and brought up. That realisation was probably part of my ‘need’ to write. However, 40 years later, I don’t really think of myself as a poet as I’ve had a full working life in education and several roles besides. Writing a poem – while sometimes difficult and prone to failure – is for me a wonderful engagement with the business of living and thinking.

Can you tell us more about your ‘busy working life’?

I taught geography in a comprehensive school for 10 happy years then, partly because of my mother’s illness, decided to take a year out and do an MEd degree, specialising in educational research. That led to jobs in that field and latterly I was Head of Assessment Research and Development for the Scottish examinations. It was at a time of significant change in educational and assessment policy within Scotland but vital to maintain standards within and across subjects and levels as they developed, while keeping an eye on assessment systems across the rest of the UK. I very enjoyed working with a talented team.

What’s in a name?

If and when I have mislaid my name

and stare at you disconcertingly

let me spend a day parked by Suilven,

perplexed by broken water. Turn

my calendar to the mountain’s season,

and set my watch by shadows on the loch.

Forgive me if I lose the reason that we came

or my gaze clouds in a cod-fish kind of way

or if the name I chose for you eludes me.

I’ll still sense mountain, water, love.

In ‘Dat Trickster Sun’, Mariscat Press, Edinburgh, 2014

In the poetic spheres, who were your earliest influences & who inspires you today?

I have always had a very eclectic taste in poetry from ‘bairn rhymes’ to serious poetry. I was encouraged by the fact that we had a few published poets who wrote in our mother tongue (Shetlandic) as well as in English: T A Robertson, Emily Milne and Stella Sutherland come to mind. I was lucky always to have teachers who had a love of poetry and was introduced to a wide range of poets including the likes of Keats, Wordsworth, T S Eliot and Burns. The Scottish ballads too were seminal. I also started to read more Scottish poets like MacCaig, George MacKay Brown and Iain Crichton Smith. Gradually the female voice appeared – we had our own Liz Lochhead and Valerie Gillies although it was mostly English and American voices that were at the forefront. Today I read quite widely (but forget quite quickly!) I love the work of Irish poets such as Michael Longley, Seamus Heaney and Ciaran Carson. There are so many wonderful Scottish poets of all ages – I couldn’t begin to list them! Many of them are now my friends. And I have friends who are poets in other countries whose work I admire too.

You write in both English and Shetlandic. Can you tell us more about your mother tongue & your work with it?

If you compare Shetlandic to Standard English, it is arguably the most distinctively different version of Scots. My Scandinavian friends tend to see it as a ‘cousin language’ – somewhere in the middle between English and their own languages. It is an older form of Scots blended with Norn, a former Norse language spoken in the Northern Isles. You’ d notice different vowel sounds (particularly ö and æ); and while vowels tend to be long, consonants tend to be percursive (with ‘d’ replacing ‘th’). And we use the familiar form of you (du, dee, dy, dine). There is a wide vocabulary as well; most words are very onomatopoeic. My mother tongue is a passion and I work to help other volunteers sustain the spoken and written forms.

This has led me to writing stories for children and working with others in a small not-for-profit cooperative (www.hanselcooperativepress.co.uk).

However, I suppose my main focus is on writing poems in Shetlandic. My aim is to write in a way which allows these ‘dialect’ poems to stand up to scrutiny and to be the equal of poems I write in English. And to help extend the small literature we have.

Glints of origin

I savoured your early words as they came,

whenever they surprised your mouth;

helped shape them with you, gather them.

How many generations of children

have quarried those same words, found

all needful sounds around them?

And sea-farers who landed here

threw in, from unfamiliar places, words

carried on ocean’s shifting tides;

wave-worn, wind-riven words,

their edges hacked aff, making

a blend; a tongue fit for saga

and for psalm. Rummage in it,

dig away, and you’ll find veins

in the stone, bright glints of origin!

********************

Glims o origin

I savoured dy aerly wirds as dey cam,

whinivver dey surprised dy mooth;

helpit shape dem wi dee, hent dem.

Foo mony generations o bairns

is quarried dat sam wirds, fun

aa needfu soonds aroond dem?

An sea-farers at laanded here

höved in, fae uncan erts, wirds

kjerried on ocean’s shiftin tides;

wave-worn, wind-riven wirds,

der aedges shaaved aff, makkin

a meld; a tongue fit fur saga

an fur psalm. Rumse ithin hit,

hock awa, an du’ll fin veins

i da steyn, bricht glims o origin!

In ‘Parallel Worlds’ Luath Press, Edinburgh, 2005

glims: gleams; dy: your (familiar); dey: they; du, dee: you (familiar); hent: collect; foo: how; fun: found; höved: heaved, threw; uncan erts: unfamiliar places; kjerried: carried; der: their; shaaved: hacked; meld: blend; rumse: rummage; hit: it; hock: dig; fin: find; steyn: stone

Your work has been translated into a number of languages. What is the sensory experience like of hearing/reading your work in foreign tongue?

It’s a delight to hear a version of one of my poems read in a different language. It’s also humbling to consider that someone has spent time getting to know the original and to dig down into its meaning, sound, rhythm and emotion. It’s very different to have a poem translated into a ‘sister’ language like Icelandic or Norwegian than into a Romance language like French or Italian. They have very different sound patterns. Part of the joy of bi-lingualism is the interaction it encourages in translation. I consider myself very fortunate to have Selected collections published in French and Italian and, within the next twelve months, in Norwegian and in Icelandic. I also enjoy translating poems – mainly from the Scandinavian languages – often with the help of an English bridge version. One particular satisfaction has been translating Finnish folk tales from the Kalevala and creating a performance with Catriona Macdonald, a Shetland traditional fiddler. Another wonderful collaboration was with Tommy Smith, jazz composer and saxophonist. Music is another family of languages! Poetry has taken me to many countries, but almost entirely beyond the UK. I hope that my recent inclusion in the wonderful Poetry Archive, may help break down the poetry barrier that seems to exist within the UK, a bit like Hadrian’s Wall.

What does Christine De Luca like to do when she’s not being, well, literary?

Besides being with family and friends, I love walking in quiet places and, being a geographer, have a deep love of landscape and natural history. I would like to be able to paint, but know I don’t have the talent. But I visit lots of art exhibitions. Living in Edinburgh offers wonderful opportunities to go to the theatre, concerts, ballet, opera. I attend church regularly and sing in our choir – that’s a joyful experience and a way of practising thankfulness. I read when I have the time and energy.

When do you know & what does it feel like to have written a good poem?

That’s a difficult question. Sometimes I know when a particular line is working well, or a particular word, or when I’ve improved a poem – all good feelings – but it genuinely takes me by surprise when people say ‘I like that poem’. As I get older I get less sure of my poems and my writing. I hope it’s because one expects more of oneself rather than the absolute loss of critical faculty! (I can still read poems by others and say ‘that’s a good one’.)

Journey

Today you see far down a mountainside,

out over islands to a sure horizon.

Your sight is sharp, your goal clear, and tides

of love lap round all your desiring.

Two sets of footprints you will make, but true

companions on this journey you’ll become.

When you slip out of step, think of today;

relive again its close embrace of freedom.

May truest feelings stir you as the wind

disturbs the loch, or smirr on cotton grass.

May you find bliss in ordinariness

and joy forever in its present tense.

In ‘Parallel Worlds’ Luath Press, Edinburgh, 2005

In 2014 you were invited to be Edinburgh’s poet laureate (Makar). What does the role entail?

I was surprised and delighted by the invitation. (www.edinburghmakar.org.uk). It is not an onerous role – you’re expected to be an ambassador for poetry in the city and to respond to occasional commissions. To a large extent one can shape the role to suit one’s strengths. I’ve tried to demystify poetry a little: to write about topics which are sometimes ignored. Having a poem paying tribute to the people who work in our Waste Water (sewage) service printed in the Scottish Sun was surely a high point! I’ve also enjoyed working with lots of other local poets. But writing ‘civic’ poetry has required me to discipline my writing somewhat! I finish my term at the end of September 2017 and have thoroughly enjoyed it.

What is the poetical future of Christine De Luca?

When I feel I’ve finished a poem, I never know if I will ever write another one. That’s a bit scary when people think of you as a poet. Maybe writing is an act of faith, in the way love can feel like an act of faith. We just go on, living in hope.

An Interview with David Lee Morgan

Hello David, so where ya from & where ya at, geographically speaking?

Hello David, so where ya from & where ya at, geographically speaking?

Born in Berlin, grew up in Carbon County Utah, Pasco Washington and Seattle. I came over here in 1983 to join in the demonstrations against the installation of Pershing and Cruise missiles in Europe. The rest of the group came with return tickets. I came with a sleeping bag, a guitar and a saxophone and a one way ticket. I’ve stayed here as a street musician ever since. I started out living in the Kukuuk, a squat in Berlin, travelled all over Europe and ended up based in London for the last 30 years.

When did you realise you were, well, talented?

i still have bouts of doubting if i am talented. Our dad was an actor and i’ve always considered performing as a natural thing that everybody can do. I loved drawing and painting and did tons of it from the time i was a toddler. When i was 14, i went off to the seminary to study to be a Catholic priest. I wasn’t allowed to paint there, so all that creative energy got talented into writing poetry and stories.

You are something of a modern day troubadour. What is it about travelling & performing that makes you tick?

My ambitions have always been as a writer, not a performer. I enjoy performing, but i do it mainly because it’s the only way i’ve been able to get the stuff i’ve written out to an audience. I would love it if other people did my shit.

As an extremely successful slam-poet, who are your poetical influences?

Biggest influence by far: Woody Gurthie. Next three: Gil Scott Heron, Gerard Manley Hopkins and Sharon Olds.

How do you know you have just written a good poem?

I’m never really sure until awhile after i’ve written it – in the heat of creation, everything seems wonderful. Then the cracks begin to appear. Sometimes i don’t realise how good (or bad) it is until i’ve performed it a number of times.

What does David Lee Morgan like to do when he’s not being creative?

Eat ice cream and watch crap videos. I should also mention a life-long obsession with philosophy, from the ancient Greeks, to Marx, Lenin, Mao to contemporaries like Alain Badiou and Bob Avakian.

Last year you brought Media Dream to the Fringe, what was it like orchestrating a piece rather than performing?

Performing a poem in front of an audience (when it works) is like having really good sex.

Seeing a play you’ve written come to life on the stage is like falling in love.

Medea Dream is just one of your many plays & novels, etc. Where do you get the energy from to be so prolific?

My productivity comes and goes. I’ve spent years working 8-10 hours a day, 6 or 7 days a week. But i’ve also gone for months, just travelling around the world, singing and playing saxophone – or watching tv and eating ice cream. I guess energy comes from motivation. I’ve always wanted to create, to draw, paint, write… and do philosophy.

Can you tell us about this year’s contribution to the Edinburgh Fringe?

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE FLOOD is a solo spoken word musical for six voices. This is the description in the program:

“A computer wakes up in the year 2035, on the eve of the world socialist revolution… Fighting has broken out all over the globe. For the first time, the US military has used tactical nuclear weapons on its own population. Suddenly, all communication stops. A new player arrives on the scene – a singularity, a computer exploding up into consciousness and fighting for sanity through a barrage of conflicting images and downloaded personalities.” THE OTHER SIDE OF THE FLOOD is the third in a trilogy of shows that will be published by Stairwell Books in the Autumn. The first, SCIENCE, LOVE AND REVOLUTION, was about… Science, Love and Revolution, and was developed through many performances, mostly in the London spoken word scene, which is so diverse and international. The second BUILDING GOD, was a history and defence of three revolutions: the Paris Commune, The Russian Revolution and the Chinese Cultural Revolution. I wrote it with the attitude – this is what i think, if you don’t like it, fuck off. But to my surprise, many people coming from many different places politically really liked it. They responded to the poetry and to the complexity of the thinking. I didn’t win them to my point of view – that wasn’t the purpose – but they said the show inspired them to think that there was a lot of history that they needed to investigate in order to get beyond the propaganda and lies. However, they went on to say, “but it could never happen again.”

So that became my challenge for this third play: not to write a blueprint or a detailed prediction of the future, but to use imagination to enable people to see that revolution was possible. As I wrote, it became clear that if the play worked, it would be about feeling, rather than just thinking that it was possible. I had a second goal as well. It’s clear that if a real world revolution is possible in any way, it must include many hundreds of millions of people who are committed to their religion. My own experience as a revolutionary communist working in the anti-vietnam war movement, was that priests, nuns and just regular Catholics involved in the Liberation Theology Movement were totally committed and totally fearless – and coming off their missionary work, had a very good understanding of imperialism and its evils. I wanted to embody this in the play. I wanted to embody an alliance between revolutionary communists (atheist) and revolutionaries inspired by their religion to fight for true justice. Because i have fairly close ties (through music and poetry) with the Bengali community, I chose to centre the play around two people: Amparo, a revolutionary communists and a leader of the Los Angeles Commune, and Hamida, a leader of the Party of Islamic Socialism of Bangladesh.

What does the rest of 2017 hold in store for David Lee Morgan?

I have been doing Free Fringe shows at the Banshee for 5 years now (plus a few earlier, going back to 1997). They have been concept shows, where i have spent a year (or more) researching, thinking and writing on the theme. After this Fringe, I am going to take a break from concept shows, and just write individual poems on whatever personal or political things hit me. I have felt constrained this year – when so many momentous things have been happening – because i have had to focus on this show, THE OTHER SIDE OF THE FLOOD. I don’t regret it. It was what i had to write about. But now i want to get back into the real world.

You can catch David at this year’s Fringe

Aug 5-25 : Banshee Labyrinth (17.10)

Speculative Books – Glasgow’s newest independent publishers

SPECULATIVE BOOKS is Glasgow’s newest independent publishing house. The High Flight fanzine and The Speculative Bookshop, a literary fanzine and pop-up book shop respectively, have joined forces in order to bring about a shared vision: getting voices heard, particularly new talents who may get overlooked by larger and more traditional publishers.

Speaking to The Mumble about how the company got started, Speculative Books co-founder Dale McMullen explained: “The Speculative Bookshop started when my pal Jen had a drunken idea to run a second-hand bookstall, which sort of petered out. Instead, we decided to start our own book fair – inviting along guest speakers, poets and artists to the pub to share their work. We were actually surprised when people turned up – and enjoyed themselves too! Since then the events and team have grown, we legitimately have the most talented writers in Scotland along at our nights.”

Speaking to The Mumble about how the company got started, Speculative Books co-founder Dale McMullen explained: “The Speculative Bookshop started when my pal Jen had a drunken idea to run a second-hand bookstall, which sort of petered out. Instead, we decided to start our own book fair – inviting along guest speakers, poets and artists to the pub to share their work. We were actually surprised when people turned up – and enjoyed themselves too! Since then the events and team have grown, we legitimately have the most talented writers in Scotland along at our nights.”

“We met the guys from the High Flight quite early on and had a mutual love of making things. So we’ve teamed up to form Speculative Books – a brand new independent publisher here in Glasgow. So far we have released Sam Small’s debut collection “Pure Toilet” and are planning on releasing a novel in the near future.” When asked about what else the future had in store for Speculative Books, Dale added: “We’re going to keep making books. For as long as we can. We’ll keep a keen eye on keeping it fresh, interesting, exciting, and above all – a good read!”

The first for Speculative Books also marks another first, with Pure Toilet being the first time popular Glasgow poet Sam Small has had the bulk of his poetry collected in one volume. Pure Toilet is a warped collection of poems; in some places wickedly funny and in others poignant and reflective. Small has a talent for making us feel sympathy with strange and maligned figures, and his unshakeable voice in getting his opinions across in spoken word format transfers just as well onto the page. This collection is the perfect introduction to Sam Small’s work, and looks to be the first of many.

Telling us about the book in his own words, Sam said: “It’s everything,” he went on, “from stuff I wrote three years ago to poems I basically just finished yesterday. I never had anything to sell at gigs, so printing a collection seemed obvious. Having a book out is kind of like the next level. If enough people buy it, you’ll start getting on at gigs in other cities more, and then just take it from there. I want to help other people be able to do that, too. There’s a lot of shit hot writers in Glasgow without anything in print.”

Keep your eye on Speculative Books’ Facebook and Twitter pages for updates on what’s coming in the near future. It’s also worth noting for any budding writers out there that they should be opening their doors for submissions in the later half of 2018. You can buy Pure Toilet from the online store at: http://speculativebooks.bigcartel.com/

Reviewer : Mick Clocherty

An Interview with Juana Adcock

Hello Juana, when did you first realise you were a poet?

When, both in reading and writing, I realised I cared more about the language than I did about the plot, and that I couldn’t stand endings. I don’t know if I have yet fully come to terms with the idea that I’m a poet, though. I always thought of myself as a writer, ie, someone who occupies themselves with the task of writing; who needs to write in order to figure themselves out. There’s nothing mystical about it, it’s just what I spend most of my time doing because I enjoy it so much. And by dint of this I’ve ended up with no other skills. I still don’t fully understand the distinction between writers and poets. Why is the genre in which we write so important? ‘Writer’ seems, in my mind at least, to be more connected to the act of writing. ‘Poet’ seems to have, at least in the minds of lots of people, all these sacred or pretentious (or cheesy!) connotations: someone who has some sort of God-given gift, who composes beautiful verses to help us through big official moments in life surrounding love, grief and patriotism… I say in my biog that I’m a poet mostly because I don’t want to annoy people by saying that I’m a writer who’s written nothing but a slim volume of poetry.

Who were your earliest influences?

Gabriel García Márquez and Robert Louis Stevenson.

THIS BODY OF A WOMAN I INHABIT

This body of a woman I inhabit, desde where I’ve lifted a hand to touch the hair on the head of Moses, [suddenly moved

to inside out tears from an entire childhood

of lips stiffened to sustain the world protect

the softness of our angles our wisdom of curtains, desde where I’ve half lowered

eyelashes to seduce three, four hombres desde where I’ve traced the sinuous “S” of desire

which Cratylus called “serpent” and Adam called “perception of flux,” desde where I’ve grown tired of nursing

like Teresa or Diana

like the fear they did not feel when touching lepers

with their immaculate hands, the lips

with which they kissed

their blessed sores, desde where I’ve washed out workshop grease

soaked fibers in a universal river of saliva desde where I’ve bled drops

miscarried fertilised wheat ivy desde where I’ve been a plot all bounty where goats graze

From Manca (Fondo Editorial Tierra Adentro, 2014)

Who inspires you today?

Anne Carson, Ocean Vuong, César Vallejo, Yuri Herrera, Silvia Federici, Zygmunt Bauman, Jhumpa Lahiri, Susan Sontag. My friends, among whom I count writers, translators, activists, musicians, artists and extraordinaires of all kinds. And the authors I translate: they are my biggest teachers, and I like being in constant conversation with them, even if most of it goes on in my head.

What motivates you to write?

My need to understand.

As a translator, what are the most difficult aspects of transcreating poetry into another language?

Translating humour and translating dialect. But the good thing about translation is that the more difficult it is, the more fun you have with it too.

Can you tell us about your first book, Manca?

I wrote Manca in Scotland, while most of my attention was directed to the violence that had quite suddenly taken hold of Mexico, my home country, during the chaos of the war on drugs, which was declared in 2006. I was reading the news obsessively and was being exposed to a lot of violent images. There only way I could deal with all that was by writing. It was a small attempt to understand that reality and transform it, if only on the page. But there is no way really to understand the horrors that the country was – and still is – experiencing. Why is Mexico currently the worst country in the world for sexual abuse, physical violence and homicide committed against children under the age of 14? What does the drug war have to do with that? And yet it is thoroughly connected: human life has no value and the rule of law does not exist. Poetry is a good tool for dealing with what doesn’t make sense and therefore cannot be spoken of in logical terms, or cannot be put into a narrative with a neat and tidy ending. But it’s not all doom and despair. Some of the poems Manca have a humorous streak. Humour is sometimes what we need when nothing makes sense. I think jokes and poems sometimes pluck at the same strings within us.

ONE-HANDED

Last Thursday I got up and decided to cut off my hand. I saw it all very clearly and when I see something very clearly I don’t dither even one second. The ultimate work of art or something like that, though I think I thought it would grow back, like hair. I started with the left ring finger. Cut just below the knuckle, flexing the finger to see better where to cut. Like cutting up a chicken. Blood didn’t spurt out. The knife was serrated and didn’t have much of an edge, but it didn’t really need one. Then the middle finger. Then the pinky. A bit of bone was left sticking out of the flesh. Half the job done I changed my mind: I remembered that fingers do not grow back, so I left on the thumb and index finger, in order to retain some of the hand’s functionality. A bandage to hide the wound. How long will it take to scar over? Interview with my father: now how are you going to work, to write? I almost always write in the notebook, or I can use voice recognition software. It occurs to me that if I learned to play the piano I’d be a lot better. With my feet. I could design some pedals…

Every day since then the knuckles left over drive me out of my wits. My bony hands. Meanwhile I work serving coffee in a café that has three storeys. I have to learn to organize myself properly according to my abilities, and remember things, and bring up the trays in the right order to avoid too much coming and going

From Manca (Fondo Editorial Tierra Adentro, 2014)

What does Juana Adcock like to do when shes not being, well, poetic?

I listen to music, and sometimes play it too, though I have no talent. Dancing, conversations with friends, and walking are also hugely important to me.

In 2016 you were awarded a Scottish Artists Fellowship to complete a writing residency at Banff Centre, can you tell us about the experience?

One of the best experiences of my life. Artists are taken really good care of there, and I would encourage anyone with a writing or translation project to apply to the amazing literary programmes they hold there throughout the year. You have everything you need to create: time, space, a fantastic library, plenty of solitude and plenty of social activities, even an indoor climbing wall and gym facilities. I loved the dinner table conversations with other creatives who were doing all sorts of interesting things: I made friends with the musicians, the writers and the indigenous visual artists. Chatting to them when I was stuck always made things unstuck, and they kept organising all sorts of recitals and talks that inevitably fed into what I was doing. A perfect balance between silence and stimulation and exchange. It was the first time in my life I felt like an artist, because I saw that my processes were not that different than what people in other creative disciplines go through (plus we were given Artist IDs! And we could buy things with them, and get discounts!). It was also the first time in my life I felt Scottish, because I was there with a contingent of 3 other Scottish artists, with whom I felt a real sense of camaraderie. And they were reliably up for a wee drink! (Bizarrely, other people seem to view alcohol as unhealthy and decadent?) And above all I loved having all these amazing mountains right on my doorstep, where I could go for long walks after writing all day. I was disappointed I didn’t meet any bears, though.

What to you makes a good poem?

There are many paths to the top of the mountain, but in general I would say surprise can be highly affecting and effective. Being faced with the unexpected does good things to the brain. Truth and authenticity are important too. And of course the music of the words.

What is the poetical future of Juana Adcock?

Hopefully completing a second collection, and some musical collaborations

PENNIES, OR HOW I SINGLE-HANDEDLY GOT US OUT OF THE CRISIS

When I arrived to the so-called united

kingdom reigned by automatons and charlatans my money

soon ran out. I found in the pantry

of the humble hostal that housed me a big jarfull

of brown penny conserve, organic and handmade in a farm in the north of France.

From that vital jelly I started stealing, a bit at a time,

to buy a pint of milk, any bread.

I rummaged too

through bins for dispersed spaghetti strands,

for peppers almost rotting.

Often in my last moments of hope

I found in a puddle a heavy pound coin

then I invested it all at once

an offering from the god of money to the god of cacao.

I stole the apples fallen to the pavement

I stole plastic rings from pound shops

I rose at dawn to slave at the till,

the coins that fell as I cashed up

stapling through my temples with their high-pitched

smell of gunshots in lands of other men stolen by other men.

It’s not mine, it’s not mine, it’s not mine, it’s not mine, it’s not yours, it’s not theirs, it’s not ours.

How many times did I walk for hours for lacking

the last missing penny for my bus fare.

But one day I cracked it: I remembered the jar of conserve, always full, no matter how much I stole.

What we needed was to plant pennies on the pavement

to gift ourselves a feeling of abundance—a penny a day

keeps your bad luck away. The sole

speculation magical intention

that transforms self-referencing money

into self-referencing money. The god of money is circular:

may it not stagnate, may it—meagre as milk—never run out

just like cows when they pour themselves out

or that clear

whisky first currency of Scotland

usige beatha first water of life

pissed out of a cow

From Manca (Fondo Editorial Tierra Adentro, 2014)

An Interview with Hannah Lavery

This weekend, Dunbar’s COASTWORD festival shall thrive once again in that glorious corner of the Lothians. The Mumble managed to catch a wee blether with organiser & poet, Hannah Lavery;

——————————————————————————–

So where ya from & where ya at, geographically speaking

I grew up in Edinburgh and moved to East Lothian ten years ago, settling in beautiful Sunny Dunbar.

So when did you first realise you were, well, a poet?

I am not sure I am there yet. I write. I have always been making up stories and playing with words and rhythm. Poet seems such an earned title or better a given one. I write poems, plays, stories- I am that. I do have a memory of composing a poem on a long car journey when I was about 10. I was with my Dad and as most children of divorce this meant not with my Mum, and I wrote about telling my missing to the star I could see out the window, but quietly so not to let my Dad hear. Writing poems, must have first been a place for me store my secrets.

Which poets inspired you at the beginning & who today?

I grew up with music played in every room and on every journey. My mum loved the theatre too and as a single mum she would bring me to everything. So Chekov, Shakespeare, Lorca, Joni Mitchell, David Bowie, Paul Simon and then later I discovered Maya Angelou and then Jackie Kay. I eventually, became an English Secondary teacher and I loved teaching Dylan Thomas and the War poets but my love of poetry and I think my desire to write it, comes though from that early love with music and from Angelou and Kay and in all those poetry books and anthologies of feminist poetry I would save up for and buy from Word Power in Edinburgh.

Meeting you

Meeting you again

in all the photos

they brought like ashes to your wake

and whilst they cooed over the boy you were,

after khow and chicken curry

with a cigarette taken from my almost sister,

another from your almost third wife, a rum to go

and with a last look back, I took what I had had

and threw it to the wind.

It did not go but settled instead to be cinders on my back,

it followed me home.

What are the best conditions for you to write your own poetry under.

I am not sure, used to be wine and heartbreak but I am a mum and it is more in the spaces between all that duty- from beneath the washing pile. I walk a lot though, in the woods, by beaches- I am lucky to live in Dunbar. And I find that poetry and stories happen in my head – later it stumbles to the page.

You are clearly a family woman – a husband & three kids, right? – how do strike the balance between familial duties & poetic creation

I am mother to three beautiful wondrous children and my husband and I have this treasured busy and crazy full family life. And it is inspiration. And yes, it is obstacle too but I do have a corner of my own and a husband who respects and supports me. We are partners raising our family and in supporting each other to have dreams outside of them too but I crave more time, more silence, less housework and I have learnt to write in the noise and the bustle, in the untidiness. I have learnt to live with the guilt of being distracted. As a mother. As a writer. As a wife.

What do you like to do when you’re not being either a poet or a mother – for recreation

We have a campervan and there, of course, I am still mother and still a writer but a more spontaneous and free one. I sit and walk and play and fill up notebooks but I am never not one of these things. Never not. And this time is so fleeting and I love it- not the chores, but them and being a gang together. My writing is inspired and powered by them mostly.

Wallflower Mothers

We grow

at the edge of you,

covering with ease

in shade,

hairline crack,

weave in

grappling hook.

Frost-proof.

Tender against

brick.

Hold tight,

create break.

Can you tell us about Coastword, its inception & its evolution

CoastWord started as the wee festival in words, and part of Dunbar Civic Week in 2013. It began as a conversation in the school playground. There is still much planning in the playground but over the years we have developed into a much bigger festival but still with the ambition to create something from our community which celebrates Dunbar and its folk and welcomes others to be inspired by our town and share their work in an intimate, friendly and supportive space. We have been lucky to have been supported by East Lothian libraries, The Dunmuir Hotel and Creative Scotland and have partnerships with Scottish Poetry Library and Dunbar Reads Together. CoastWord is a such special few days and something I am so proud of being involved with.

Who do you have in store for us this year?

We have loads! Poetry with Magi Gibson, Jenny Lindsay, Scott Tyrrell, Colin McGuire and many more in a special Spoken Word and Music night and in events throughout the weekend including a CoastWord Big Breakfast with Katherine MacFarlane and Julie Hogg. We have theatre with Village Pub Theatre and Jenna Watt’s award winning play, Faslane. Authors Val McDermid, Christopher Brookmyre, Janice Galloway and Shelly Day. Music from Faith Eliot, Kirsty Law and Dunbar Sings. Along with new work from our Writers in Residence 2016-17, Catherine Simpson and Kirsty Law.

What does the rest of 2017 hold in store for Hannah Lavery

I have been fortunate to have received a Megaphone residency from Workers Theatre and will be sharing my work The Drift in June at their pop up festival in Glasgow. I am also proud to be part of the Writing Mums Anthology, Nourish Me, Sister, which will be launched at CoastWord. This year will also see me working on my first pamphlet of short stories to be published by Post Box Press in 2018.

I am also looking forward to working on some workshops with North Light Arts and the Ridge Project in Dunbar. And of course, I will be working on CoastWord 2018.

Coming Home

My hand reaches in.

It returns empty

twice.

My fingernails

retrieve sodden fluff,

biscuit crumb, keys-

he grabs them.

She needs a wee!

He opens the door,

the boys push and

we tumble in.

Untangle ourselves

for loo, Xbox, fridge.

He comes at us

a trip hazard.

Bum and tail

swaying pendulum.

I hold to

one of you

unsure which,

wade through

shoes and coats.

I am barely home

and you are before me

a knight, super -hero, turtle.

Coffee is being made.

I dodge an arrow.

Shift a gym bag-

coorie in.

An Interview with Katharine Macfarlane

THE MUMBLE : Hi Katharine, when did you first realise you were a poet

KATHERINE : Oh I’m quite wary of the word poet, as it’s not really a title I’d lay claim to. I’ve always loved the rhythm and flow of words and for as long as I can remember have had lines from poems, songs, stories intertwined with visuals – like a mini movie- running through my mind. I recently found a Spot the Dog Notebook from when I was in primary school that’s full of songs with a syllable count for each line so I was obviously interested in the rhythm and structure of pieces from an early age and I remember in P6 a headteacher from another school came to judge the Burns Federation competition; she’d told us a wee story and even as she was telling it I could hear it weaving into a poem, so I wrote it down & she sent me a lovely wee gift in exchange – I guess I learnt early that poetry pays!

That said, I stopped writing when I was 21 – a combination of lack of confidence and a feeling that it was time to ‘grow up’. I always felt like I’d Hartnett’s scars from his Necklace of Wrens tho and still thought in stories and poems. I only started sharing them again a few years ago. As I tend to construct pieces in my mind rather than on the page it’s been a total joy to be able to participate in a vibrant Scottish spoken word scene that has echoes of the traditional ceilidh house.

——–

THE MUMBLE : Who were your earliest influences?

KATHERINE : Robert Burns. I struggled with the language but his metaphorical use of the natural world really chimed with me and then later, in secondary school, it was Gaelic songs and poems, Celtic and Norse myths and traditional ballads that influenced my thought process and in turn the content and style of writing. The first time I read Meg Bateman’s work was at school in a collection called An Aghaidh na Sìorraidheachd and I remember being struck by the clarity of her writing and the gentle delivery of multilayered, often challenging stories with so few words. There was a realness to her writing, it was passionate & strong without being over dramatic or angst-ridden and that appealed to me. John Glenday, Robin Robertson, George MacKay Brown, Norman Maccaig have all influenced the way I think about poetry as has landscape writer Robert Macfarlane. I’ve always been influenced by lyricists, most recently songwriters like Ross Wilson of Blue Rose Code & Georgia Ruth and now of course I’m influenced by the many amazing spoken word performers and poets that I hear reading at events across Scotland.

THE MUMBLE : What motivates you to write?

KATHERINE : Short answer? Everything. There are always words drifting through my mind, usually rooted in the language of landscape and often sparked by minutiae of the natural world (I can be distracted by seaweed at low tide or the way sunlight glints on silver birches all too easily!) but they’re just as likely to be triggered by stories, place-names, historical events or individuals (particularly those not well represented in traditional historical accounts) and they’re always driven by an emotional response. But what motivates me to shape them into longer pieces and share them is very simple; connection.

I enjoy that feeling of connecting directly with the audience during performances, in longer sets there’s usually some audience participation as I enjoy creating something together and love to hear about the connections people make between the pieces and their own experiences. The pieces with a historical or geographic connection seem to spark these the most – there seems to be a real desire to talk about our history, culture and landscape, even if it’s just reminiscing about places people went to on childhood holidays or stories their granny used to tell. I love hearing other people’s stories.

THE MUMBLE : You are a top natch slam competitor, what are the fundamental differences between poetry on the page & poetry performed

KATHERINE : Oh I’m a Slam Baby! I only went to my first ever Slam in June last year and loved the quick change nature of the evening – hearing all those diverse voices in just a couple of hours was an exhilarating experience. I always come away from Slams with adrenaline flowing whether I’ve been competing or just listening. But we’re incredibly fortunate in Scotland and there are a wide range of poetry events out with Slams from open mics to regular shows like Loud Poets, Interrobang or Flint & Pitch and longer form sets from emerging and established artists both from Scotland and further afield. This is due to the hard work of the many dedicated poetry promoters here in Scotland – it’s an exciting place to work but they are working extremely hard on very limited ,or nonexistent funding to try to deliver entertaining events that also provide diverse, accessible opportunities for performers, I think they all deserve some kind of poetry sainthood for their patience & commitment!

I’m slightly dodging the question about the fundamental differences between poetry on the page & poetry performed? Sorry! I suppose that’s because I feel that fundamentally there isn’t really a difference between poetry on the page and poetry performed. Or at least that there is no real requirement to make a distinction between the two. Until recently, ok several hundred years ago (!), poetry was always performed and, for me personally, regardless of whether a piece is performed or written, what matters is that it is true to the author’s voice and that it connects or resonates in some way with the audience whether that’s through the content, clarity of observation, rhythm, or beauty or unexpectedness of the language.

Of course, in a slam style situation where you have 3 minutes to connect directly with the audience and where you know they will be hearing lots of poems in quick succession it makes sense to speak more directly than you might if your pieces were contextualised as part of a longer form set or, I guess, if you were writing for publication where your audience can revisit them time and again. So yes, my Slam material is different from some of my other work in that it’s much more direct – but as I always compose material in my head and rarely write any of it down, unless I’m sending it to someone, I never really consider how it works ‘on the page’ …so I’m probably the wrong person to answer this!

——————

THE MUMBLE : Can you tell us about your first solo show, Home Words, you performed at last year’s the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.

KATHERINE : Home Words:Waulking explored themes of identity, violence, loss, survival and belonging with my own writing both inspired by and performed woven amongst traditional Gaelic waulking songs. Waulking was a means of processing tweed by hand, it was undertaken only by women and the full process was accompanied by song- some of them traditional songs that were passed down orally, others extemporised at the waulking itself. The waulking songs that have been recorded provide an invaluable record of women’s experiences from a time when women, particularly women from lower social classes and remote geographic regions, are not represented in traditional historical accounts. Much of the material contained within the songs is directly relatable despite the passing of often hundreds of years since their composition with topics such as; family life, motherhood, love, loss, sexual and domestic violence, politics and feelings of disempowerment in a patriarchal society addressed at times with poetic beauty and at others with an almost heart-breaking bluntness. The fact that a Waulking was a women only ‘safe space’ I feel lends an added profundity to the material. And of course I invited the audience to join me in Waulking the cloth and singing some of the songs with me…it was great fun, there was probably more giggling than singing from all of us and my goodness it was hard work! Those women must’ve been very fit!

THE MUMBLE : So what does Katharine Macfarlane like to do when shes not being, well, poetic

I’m a children’s librarian and mum of 2 story and song obsessed children. So life really is just full of stories, songs and poems all the time! I spend as much time as possible on beaches or walking out by the Loch or in the woods as that’s where the words flow easiest. Nights in are usually spent reading stories & songs that spark the writing and nights out are usually spent at poetry events…oh good lord…turns out I’m never not being, well, poetic!

Selkie

THE MUMBLE : Can you tell us about the Voices from Ashes project

KATHERINE : Voices from Ashes is a collaborative art project with the wonderful visual artist Karen Strang. It blends word and image to produce a creative reimagining of women‘s voices.

The project was inspired by a shared interest in both the Scottish witchcraft trials and in the representation of women in the written historical record and the work has always been inspired by site visits, shared reading and a discussion of historical analysis. But from the very beginning there’s been an almost spooky, organic development of shared symbolism. Some pieces of writing are inspired by the artwork and other pieces of artwork have been produced in response to the written word. This year Karen will exhibit in Crieff, Milingavie and Falkirk with each exhibition incorporating original poetry composed specifically for each exhibition and reflecting local events.

—————–

THE MUMBLE : What is it about the Scottish Witchcraft Trials which made you want to turn them into art?

KATHERINE : Initially my interest in the project was driven by an exploration of the impact of the long term marginalisation of a specific sector of society to distract attention from and/or legitimise the actions of a detached ruling elite that was orchestrated through the means of mass propaganda, scaremongering and the exploitation of an inherently skewed criminal justice system. The echoes of these actions are still with us and reverberate through the written pieces produced for the project.

I originally studied history at university. I love the way that history is like a magic mirror that reflects our past actions and decisions back to us and allows us to fast forward to see what the results of those actions were…and I know there are always immeasurable variables between historic conditions and current situations but well, people are still people and much of the drivers and motivators are the same as they ever were I’ve always been drawn to the human stories, the individuals, it’s these voices that I find running through my work time and again. In the traditional historical accounts of the Witchcraft Trials the women’s personal experiences, emotions, feelings are notably absent but it’s not hard to hear their voices if you listen and so Voices from Ashes aims to redress in some small way the injustices of the SWT by giving back the herstories of the victims in images and words based on an emotional response to the facts recorded at the time of the trials and also to serve as a memorial to the women cited. We hope to create pieces that generate discussion around the Witchcraft Trials and in a wider sense how we, as communities, respond in times of uncertainty or societal change.

——————-

THE MUMBLE : What does the rest of 2017 hold in store for Katharine Macfarlane, the poet?

KATHERINE : I ❤️2017! It’s been an amazing year so far and there’s plenty more excitement to come including; Some Gaelic songs and storytelling at the Flint & Pitch Revue 5 at the Bongo Club in Edinburgh on 21st April, a breakfast show at Coastword Festival in Dunbar on 21st May, a special appearance as my alter-ego Bird Girl at Freak Circus as part of the Hidden Door Festival on 27th May, a performance at the St Magnus Festival in Orkney in June with Enterprise Music Scotland Artists in Residence – Alison McNeill & Sasha Savaloni and of course another Bella Slam at the Belladrum Festival in August.

Voices from Ashes is mainly about the fine art exhibitions this year but we’re planning to run some workshops in conjunction with the exhibitions in Crieff and hopefully the project will grow to encompass creative writing & painting workshops in other communities touched by the Scottish Witchcraft Trials.

Shawbost

An Interview with Matthew Rice

THE MUMBLE : Hello Matthew, so where ya from & where ya at, geographically speaking

MATTHEW : Hi! I was born in Belfast, Northern Ireland and was raised via Rathcoole (a housing estate outside of Belfast) and Islandmagee (a peninsula on the North East coast of Antrim), ending up in Carrickfergus, County Antrim, where I currently reside.

THE MUMBLE : When did you first realise you were a poet

MATTHEW : I don’t think i ever ‘realised’ I was a poet. I’m a little wary of folk who make claims to the art; which is to say, I believe it comes from ‘elsewhere’, as Ciaran Carson might put it. For a lot of years I felt I was just a reader, not a writer. Having said that, I came third in a short story competition for children when I was 10 years old, and I wrote little poems and such during those years also. I can tell you that I began to write poetry in earnest, as they say, when I was 27 (I’m now 36); the catalyst was provided by a visit with my father (himself a successful poet, Adrian Rice), to the WB Yeats exhibition in Dublin back in 2006. Although it must be said that I was probably absorbing poetry from an even younger age, given the amount of famous poets that came in and out of our house in Islandmagee, on account of my father’s involvment in the art.

THE MUMBLE : Which poets inspired you then, & who today

MATTHEW : Poets who inspired me when I started out were the likes of Seamus Heaney, Miroslav Holub, Elizabeth Bishop, Sylvia Plath, Michael Longley. The poets that inspire me now are the same, but with the discovery of the complexities of Paul Muldoon’s work a joy; and Don Paterson is a hero of mine also. There are a number of emerging poets that I very much admire. The likes of your own Ross Wilson and Stephen Watt being just two – I had the pleasure of reading with them in Glasgow last November, as well as the inimitable Magi Gibson – along with exciting new Irish contemporaries both in the North and South. The ever-presents are Heaney and Longley, though. And my father, Adrian, of course, has always been a mainstay and an inspiration, and is a brutally honest giver of poetic feedback, which is valuable to have.

THE MUMBLE : Being an Ulsterman, do you find the socio-politcal stresses strains of your native land coming out in your poetry

MATTHEW : To a certain degree they have done, in some of my work. Funnily enough I’ve written a few poems with strains of the WWII Holocaust in them; my poem in memory of the late great poet Primo Levi being one. If I have ever addressed that area in my poems it has always been from an angle of Greek or Roman mythology, or from a childhood perspective. This is nothing new, of course, but is how I feel I can get at what I want to say; and is probably also why it has featured sparingly in my poetry to date. Once you’ve read ‘Ceasefire’ by Longley, ‘Anseo’ by Muldoon and ‘Casualty’ by Heaney, it’s really pointless to think one can compete. Plus things are much improved in my adult lifetime

THE MUMBLE : What other forces drive your work

MATTHEW : Nature can be one. Dreams have also provided me with many a poem. And history. I enjoy linking historical events to events in the present, if possible. I think history can be a lens with which to provide a sharp focus on events in the present, and the recent past. The events concerned do not necessarily have to be of a political nature, either. Personal experience is another aspect that I like to represent, although I find most times the speaker in those poems is fairly impersonal, for whatever reason; I’m not sure myself…

THE MUMBLE : You have had poems published in magazines and journals on both sides of the Atlantic, how do you find both the American poetry & the British scenes of 2017 – is there any common ground

MATTHEW : I find that the American scene, judging from what I’ve read in the journals and from my father’s experience as a ‘poet in exile’ there for the last 12 years, is thriving, as it is in Ireland. The UK is producing some great stuff. I must say, though, there is something special in the air in Belfast… There’s a real poetic buzz about the city these days, and it’s exciting to be a part of it. As far as common ground is concerened, the experimentation on both sides of the Atlantic in verse is something I have noticed. Free verse is also alive and kicking across the water, though I have seen the sonnet form more prevalent on this side; Adam Crothers and Adrian Rice just two prime examples. But any form I love, if the poetry is good. It’s also great to get to follow names in America that don’t necessarily get big coverage in Ireland by being published in those US journals; the likes of Stephen Dunn and Fredrick Seidel, to name two.

THE MUMBLE : What to you makes a good poem

MATTHEW : For me, a good poem is one that is first and foremost honest; one that does not rely on what Raymond Carver might have referred to as ‘tricks’. A good poem comes from what Heaney referred to as ‘a genuine impulse.’

THE MUMBLE : What is the poetical future of Matthew Rice

MATTHEW : Well, hopefully poems continue to be given, as that is where the real work is done; that inspiration continues to hold, and that ‘genuine impulse’ remains clear. Other than that, I have been included in the upcoming anthology ‘The Best New British and Irish Poets 2017’, being launched in London from Eyewear Publishing on 2nd April, and in Belfast on April 20th. I also have a poem in a future anthology in Scotland. I have a few poems forthcoming in one or two journals, as well as some exciting news I just received that has yet to be officially announced… But working towards my first collection is where the focus lies in the immediate future, continuing to refine and sharpen that manuscript, giving it the best chance of becoming my first book.